Article Index

Note: Brian Wright filmed this adventure. Unless otherwise indicated the images were poorly extracted by me from a VHS tape.

I don’t remember when I first saw a photo of Mount Assiniboine but whenever it was I was smitten by its beauty. Assiniboine along with the Matterhorn and Ama Dablam are, perhaps, the most attractive climber’s peaks in the world. The latter two were likely beyond my reach but Assiniboine was just next door to Idaho. Early on in my life when I was an armchair mountaineer I read Frank Smythe’s Climbs in the Canadian Rockies, (1950) Hodder, London, which included a harrowing recitation of Smythe’s solo attempt to climb the peak in icy conditions. Between photos and Smythe’s book the “Matterhorn of the Rockies” siren call was seductively calling me for many years.

Mountain Assiniboine and the headwall viewed from the Assiniboine Lodge. Edna Winti Photo via Wikipedia

Mount Assiniboine lies on the border between Mount Assiniboine Provincial Park and Banff National Park. It rises to 11,867 feet and stands 5,003 feet above our planned starting point at Lake Magog. It was first climbed by James Outram, Christian Bohren and Christian Hasler in 1901.

In 2001 the time was right to make an attempt of the peak. On July 17th Brian Wright and I flew to Calgary, Alberta intent on climbing the peak. We were well aware that Assiniboine is a difficult mountain to climb. It combines serious exposure and rockfall hazard with technical rock climbing. From a practical standpoint the standard route sounded no more difficult than the Grand Teton which I had climbed. From a logistical standpoint Assiniboine was not an easy peak to reach. From a realistic standpoint work limited the time I had available which was a factor that could impact our chances of success. While we hoped for dry conditions because we knew the Canadian mountain was known for its uncooperative weather. Thus, in the event that the mountain could be covered with snow and ice Brian and I decided to hire a climbing guide to increase our chances of success. We made arrangements through Yamnuska Mountain Adventures in Canmore, Alberta.

We arrived in Calgary to find sunny skies. After renting a car we drove to Canmore, checked into a hotel and then stopped at the Yamnuska Mountain Adventures office where we met our guide, Rod Gibbons. The manager informed us that the weather forecast was less than ideal and suggested we consider an alternative peak farther north where the forecast was more favorable. We decided to stick with the plan.

We were scheduled to start the climb the next day and had the afternoon free and decided to take in the sites. We drove north to Lake Louise. The closer we got to the lake the darker the sky. By the time we reached the lake a steady rain was falling and the temperature was dropping.

We returned to the hotel and started to debate our options. We knew the rain portended fresh snow on the higher peaks and would limit our chances of success. I told Brian that Frank Smythe’s advice found in Climbs in the Canadian Rockies regarding the less than ideal Canadian Rockies weather was to not wait for good weather to make your approach. After a bit of back and forth we decided that we came a long way to climb Assiniboine and we had to give it a try. We turned to getting our packs ready. Yamnuska had given us the food to carry which didn’t look all that appetizing. We stuffed the bulky food into our packs, made final adjustments to our gear and hoped we would awake to clear skies.

The next morning we woke to overcast skies. At least it wasn’t raining. Buoyed by the slight improvement, we headed to the Yamnuska office. The manager, once again, cautioned that this slight improvement in the weather was not a guarantee that the conditions were improving. Since we had three potential climbing days at our base camp we decided to stay the course hoping that the rainy weather would clear one of the next three days. We were then driven to the helipad to catch our helicopter flight to Lake Magog, 7,008 feet.

It started to rain almost immediately after we took off. The flight, even with the rain, gave us views of the spectacular terrain of the southern Canadian Rockies. We crossed deep valleys bordered by imposing near vertical sedimentary peaks. We landed at the Assiniboine Lodge on Lake Magog. An idyllic resort with beautiful cabins and noted for its expansive views of the big mountains. However, the lodge’s famous view of Assiniboine was masked by a stifling cloud ceiling. A steady but light rain was falling.

Our destination for the day was the RC Hind Hut at 8,050 feet. The route covered four miles. While the day’s route only gained just over a thousand feet of elevation 700 feet of the thousand would be incurred climbing a nearly vertical headwall. We hoisted our packs and followed Rod along the north side of Lake Magog toward the imposing and seemingly impenetrable headwall that rose up west of the lake.

The route up the exposed wall was not obvious but was well known to our guide. He had us rope up on the most exposed section of the wall as we climbed a series of exposed, narrow ledges and gullies. The climbing never exceeded Class 3 in difficulty but because of the exposure felt challenging. The steady rain continued to fall as we climbed. Above the headwall we climbed onto a 25 degree snowfield which lead up to a large black cliff. Everything above the cliff was shrouded in clouds.

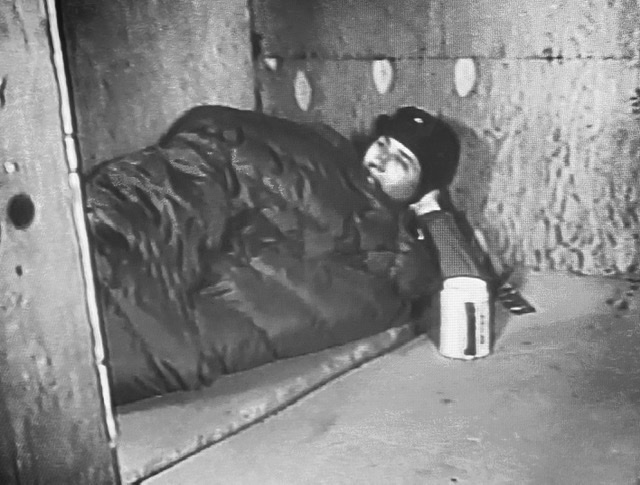

Rod told us the R.C. Hind Hut was located on the top of the cliff. We followed him up the slushy snowfield and then around the right side of the cliff. The R.C. Hind Hut was a Quonset hut that provided a welcomed refuge. It was a relief to get out of the rain into the relatively comfortable and most importantly dry shelter.

Walking across the snowfield at the top of the headwall. The hut is located at the top of the black cliff.

Although we were told that that hut is often crowded in July it was empty when we arrived. Evidently, the weather had kept other more intelligent climbers away. The unheated hut has one room. There were sleeping platforms with foam mattresses. It looked like 12 or more climbers could crowd into the hut. There was no lighting but there was a table, benches, a propane stove with fuel, pots, dishes and utensils as well as an Emergency Radio Phone. There was also an outhouse. The hut was managed by the Assiniboine Lodge and reservations were required. Rod also told us that the hut was named after Robert Hind, a legendary Canadian climber who was very active in the Alpine Club of Canada. The ACC built the hut for BC Parks in 1971.

We set about drying our gear and making ourself comfortable. While Rod made dinner, he told us a little about himself and shared a few climbing stories. Rod was originally from Illinois but developed his climbing skills in Colorado. After he married a Canadian woman they moved to Canada. He went through the necessary steps to qualify as a certified climbing and backcountry skiing guide. He had started guiding in 1987. Rod seemed ageless. He was a good natured, steady Zen-like climber who’s confidence was contagious.

As nightfall creeped up the rain let up but the cloud bank was holding just above the hut. We planned to get up at 3:00am in hopes that we would wake to stars. At 3:00am it wasn’t raining. It was snowing lightly. Disappointed but not surprised we climbed back in our sleeping bags. I recalled Frank Smythe’s description of his August attempt in similar conditions as I drifted off to sleep. I acknowledged to myself that our chances of reaching the summit were now slim at best.

The route used by Yamnuska is the Northeast Ridge which climbs steeply for 3,000 feet to the summit. Rod said “the exposure is serious this route is not too technically difficult.” Rod described the route noting it started by climbing up a series of gullies which began near a saddle north of the hut. The gullies led to the base of a rock band. The route climbed up through the rock band and then moved onto the ridge crest. Once on the ridge crest we would follow it to the ‘Red Band’. Rod said the Red Band is the crux of the climb pointing out it involved several hundred feet of 5th Class rock climbing. Once above the crux we would an easy “walk” to the summit. Of course up until this point we had no chance to observe the route. No doubt the climb would be challenging in dry conditions. Given the weather conditions it was likely the route was going to treacherous.

In case you are wondering why we pressed on to this point when the weather was so bad I will explain. We had to make reservations well in advance. The reservations included a guide from July 18th to July 22nd and the helicopter flight on the 18th. Additionally, we both had work commitments which prevented us from hanging around until the weather improved. When we discussed the forecast with Yamnuska on our arrival they suggested other alternative climbs. Bryan and I decided, like Frank Smythe many years earlier, that we came a long way to climb Assiniboine and we were willing to gamble on the weather.

Rod started breakfast around 8:00am. The snow had changed to a snow rain mix. It wasn’t very cold but it certainly looked like conditions were not going to improve any time soon. Rod suggested retreating but Brian and decided to give it another day. Rod suggested climbing Mount Strom, 9,915 feet. This not only saved us from sitting in the hut all day but gave us a chance to actually climb a mountain. The precipitation stopped but the hut was encased in fog. Mount Strom turned into a nice snow climb. The route started by climbing up a sharp snow ridge to rock wall. We climbed the wall on its left side and then ascended the final snow slope that led us to the summit. Visibility was so bad that if the summit had not held a 5 foot tall cairn and a summit register we would not have known we reached the top. Most of the climb the fog was so thick you could not see more than 50 feet. Thus, my first Canadian summit was not blessed with a view of the spectacular “Matterhorn of the Rockies.”

Rod led us down the peak’s southwest Ridge to the saddle that connected to Assiniboine’s northeast ridge. At one point the clouds lifted and we could see a small lake far below. However, we could not see any part of Assiniboine’s northeast ridge. Back at the hut Rod called the Assiniboine Lodge to get a weather report. The report was not encouraging. Rod suggested a couple of alternative climbs near Lake Louise as the weather forecast farther north was still more favorable. This time Brian and I decided to follow Rod’s suggestion. He made arrangements for us to fly back to Canmore the next day.

Despite the failure to even get a look at Assiniboine the attempt was a grand adventure. We not only got a nice consolation prize in Mount Strom but we had experienced the majesty of the Canadian summer weather in a rugged environment. We had an uneventful descent down the headwall, a snack at the lodge and a foggy flight back to Canmore. Although the rain continued off and during our retreat the weather in Canmore was dry.

The new plan for July 21st was to climb Mount Niblock 9,764, and Mount Whyte 9,786 in Banff National Park. These two peaks rise above Lake Louise. Both these peaks were named after big shots with the Canadian Pacific Railway. Both are similar in form to peaks found in Idaho’s Lost River Range. Reading about the route I really didn’t see the need for a guide but we had already paid for one and we liked Rod. The three of us got an early start the next day.

This photo show the route up Mount Whyte (left) and Mount Niblock (right). I extracted this photo from a Medicore Amateur video which shows the route in detail. Click on the link below to view the video.

Mt. Niblock was first up. The trail to both peaks started at the Chateau Lake Louise. We followed the trail past Mirror Lake and then Lake Agnes. At the west end of the second lake we started up a steep talus slope and then climbed up a few short cliffs. Once on the saddle between the two peaks we headed north to Niblock. The route was mostly Class 2. After enjoying the expansive view we returned to the saddle and started up Mount Whyte. The route up Whyte was a bit more strenuous and more exposed but once again not difficult. Climbing the two peaks encompassed six miles and just under 4,000 of elevation gain.

Our Canadian adventure was over. We were fortunate to bag three peaks and experienced a small slice of the magnificent country. We said goodbye to Rod after returning to Lake Louise. The next day we were back in Boise.

Next: Mulhacén

Article Index