This article was first published in Idaho Magazine, March 2021 (Vol. 20, No. 6)

“Time is relative; its only worth depends upon what we do as it is passing.” —Albert Einstein

Mountain climbing, like life, is more about the journey than reaching the summit. My journey with Bell Mountain, one of Idaho’s iconic landmarks, began in 1978. I had just started working for the Bureau of Land Management in Salmon, Idaho. On my first weekend, I drove to Idaho Falls to visit my great aunt and uncle. The trip was my first drive down ID-28. This highway traverses the wide mountain valleys situated between two large fault block mountain ranges: the Beaverhead Range and the Lemhi Range. As the highway leaves Salmon, the valley quickly widens and the mountains on either side rise in height. The view from the road is filled with attractive peaks. As a climber, I made mental notes of many of these peaks as I drove.

Mountain climbing, like life, is more about the journey than reaching the summit. My journey with Bell Mountain, one of Idaho’s iconic landmarks, began in 1978. I had just started working for the Bureau of Land Management in Salmon, Idaho. On my first weekend, I drove to Idaho Falls to visit my great aunt and uncle. The trip was my first drive down ID-28. This highway traverses the wide mountain valleys situated between two large fault block mountain ranges: the Beaverhead Range and the Lemhi Range. As the highway leaves Salmon, the valley quickly widens and the mountains on either side rise in height. The view from the road is filled with attractive peaks. As a climber, I made mental notes of many of these peaks as I drove.

Sixty-five miles south of Salmon, the highway crosses Gilmore Summit and then begins a long, sweeping decent toward the Snake River Plain. The land is open, treeless terrain with huge alluvial fans pouring down from the mouths of dark, tree-filled canyons crowned by windswept summits. Suddenly, I spotted a stunning, Liberty Bell-shaped mountain. It towers over its otherwise impressive neighbors. I stopped the car and pulled out the road map. There were only two peaks identified by name on the map: Bell Mountain and Diamond Peak. The northernmost of the two peaks is Bell Mountain. An appropriate name, I thought. This moment was when my infatuation with the mountain began. I knew I had to climb it.

There are many reasons to climb a mountain. There is the challenge that a mountain presents. We wonder if we measure up to the challenge? There is the lure of exploring the mountain’s wild, remote, and possibly unvisited terrain. We wonder “has anyone climbed that peak?” There is the promise of the stunning vistas a mountain summit inevitably possesses. We wonder about and long to discover “what will I find up there?” There is also the unexplainable inspiration that an attractive mountain plants in our minds. Its shape might be the draw. Its height or remote location may create a desire to unlock its secrets. It may be that all of these factors combined create a sense of foreboding or mystery that somehow overwhelms our better judgement and draws us upward. Maybe I am overthinking the process. Maybe the “why we climb” is less complicated. George Mallory, when asked why he was trying to climb Mount Everest in the 1920s, simply answered “because it’s there.”

The first step in climbing any mountain is to research the access route and to ascertain the climbing difficulty. I quizzed my great uncle about Bell Mountain. He told me about Mount Borah but he knew nothing about Bell Mountain. I asked a rugged-looking salesman in an outdoor equipment shop. He at least had driven by the peak but imparted no useful information. I unsuccessfully looked for a guidebook in two different Idaho Falls book stores. It became clear that finding information about the impressive peak was not going to be easy. Back in Salmon, none of my coworkers were climbers or were the least bit interested in the peak. Sometimes your research is fruitless. In those cases, the only option is to just give it a go and try to climb the peak.

Time passed. Eventually, I uncovered a few facts about the peak and the Lemhi Range. The range runs over 100 miles from Salmon in the north to the Snake River Plain in the south. It is only 15 miles wide and steep and rugged on both sides. The range was relatively unknown outside Idaho and not even well known in Idaho.

Surprisingly, this distinctive bell-shaped mountain was not named Bell Mountain because of its shape. Instead it was named after Robert Norman Bell, who was Idaho’s State Inspector of Mines in the early 1900s. USGS surveyor Thomas M. Bannon made the first known ascent in 1914. However, it is likely that ever-inquisitive prospectors ascended the peak at a much earlier date. Soon after Bannon’s ascent, in 1916, the name Bell Mountain was included on an early sketch map of the Nicholia 30-minute United States Geological Survey quadrangle map.

A year and a half passed without an attempt at climbing the peak. I transferred to the BLM’s Idaho Falls office. I was a crew leader supervising a Young Adult Conservation Corp crew. In March of 1980, my crew was assigned the task of building range fences in the Little Lost River Valley. We established a camp on Wet Creek due west of Bell Mountain. We worked long hours, four days a week. Each day, the snow-covered mountain stood over us as we worked. Each day, the mountain’s siren song enticed me.

Bell Mountain as viewed from my work camp along Wet Creek in the Little Lost River valley. The snow we would encounter in the trees was not visible from camp.

In mid-April on a Thursday evening, I returned with the crew to Idaho Falls for the weekend. I could wait no longer. It was finally time to make the climb. Dana Hansen and I along with our 14-year old Australian Shepard Samantha drove back to my work camp on Wet Creek intent on climbing Bell Mountain.

The snow had receded significantly and, from the valley, a mostly snow-free ascent looked possible. The next morning, we drove to Basinger Creek at the base of the peak’s west ridge. We parked and started our ascent with a steep climb up a sagebrush slope to the broad ridge crest. We were young and felt invincible. I remember singing a parody of Steven Foster’s Camptown Races substituting “Bell Mountain climb” for “Camptown races.” Nowadays, I no longer waste energy or breath with unnecessary talking or singing when climbing steep slopes.

The ridge climbs relentlessly from 6,600 feet to the first high point at just over 10,200 feet. At 8,000 feet, we entered the forest and, at 9,000 feet, we started to encounter sporadic snow drifts. A bit farther up the forested ridge, the snow cover became continuous. The farther we climbed, the deeper the snow. This was an unwelcome impediment but we pushed on.

After crossing the 10,201-foot ridge point, we were able to link together a few snow-free spots before we ran into waist-deep, unconsolidated snow. The snow would momentarily support our weight before giving way. We would plunge down, at times to our waists. The shock forces the air out of your lungs. Occasionally, the snow supported us for a few feet raising a hope that the worst was over. Whoosh, the snow collapses and hopes are dashed. Crossing the deep snow without snowshoes is tiresome at best and deflating at worst. Take a step, fall through the snow, repeat.

We crossed a large ridge-top meadow by wallowing through the deep snow, taking turns breaking trail. On the other side of the meadow, we encountered rocky outcrops that blocked our way. Remember, we knew nothing about the route other than the few details revealed by our map. Skirting these obstacles involved crossing deeper and steeper snow fields. After passing the first obstacle, we snacked. Looking at my watch, I was surprised by how much time had passed.

Climbing on, we finally reached a small rocky outcrop at 10,800 feet. It was 3:00PM. We had optimistically thought that we would have completed the entire climb by this time. Instead, we were still 800 feet below the summit. Added to the remaining elevation gain was the knowledge that the return hike through the snowy terrain was going to be another tiring slog. Samantha was showing her age. She curled up in the sun and fell asleep. The spectacular 800-foot tall west face towered above us and looked beyond Samantha’s climbing ability. We discussed the options: turn around or shuttle individually to the summit while one of us stayed with the dog. From a time perspective, it was clear that there wasn’t enough time to shuttle up the mountain. We still had to drive back to Idaho Falls and go to work the next day.

Summit fever is an ever-present desire to reach the top that often clouds a climber’s better judgment. The closer you are to a summit, the stronger the effect that summit fever exerts. It often motivates me to continue on to a summit when my body, mind, and better judgment are telling me to turn around. Turning around at this point, I told myself, would be sacrilege. Dana volunteered to wait. I decided to press on. We agreed that I would turn around at 4:00PM whether I reached the summit or not.

I dropped off the knob and waded through the last punky snowfield leading to the base of the snow-free west face. I climbed up rocky steps taking care to avoid dislodging the abundant loose rock that covered the ledges. I was tired. I kept expecting to reach the top at any minute. At 3:45PM, I checked the barometric altimeter I carried. It read 11,200 feet. I could not believe that I had only gained 400 feet in 40 minutes. I knew that I could not do another 400 feet in the fifteen minutes left before I had agreed to turn around. Dejected, I started down. Disappointed but energized by our near miss, we vowed to return more than once as we made the long, tiresome descent.

Four weeks later, we once again returned to climb the peak only to find that a late May snowstorm had blanketed the upper reaches of the peak with two feet of fresh snow. This time, we turned around at 10,000 feet unwilling to post-hole through the drifts. Finally, on August 30, 1980, we reached the summit. I discovered that when I turned around in April, I was less than 200 feet below the summit. The altimeter’s faulty reading had mislead me. The view and the accomplishment validated all the effort we had expended. The climb was all that I had imagined and more.

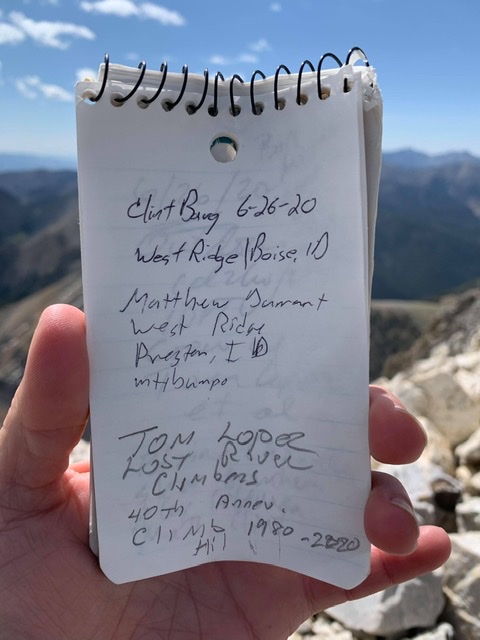

On the summit, we found a register documenting that others had climbed the peak. The makeshift summit register documented many climbs by people from as far away as New England. Members of the Amy family of nearby Howe, Idaho seem to have a special claim on the peak. They had signed the register almost every year for as long as there was a register. The register documented that on an average year, ten climbers reach the summit.

There are so many personalities that make up a big mountain. I was not through with the mountain. In 2004, I climbed the peak again with an all-star group organized by Dan Robbins. In addition to Dan, the group of Idaho climbers included Richard Wallace, Craig Peck, Dean Lords, and Mike and Josh Howard. We climbed the Southwest Gully Route which was first climbed in 1963 by the EE DA HOW Mountaineers, Lyman Dye, Art Barnes, and Wayne Boyer. This was a more difficult, steeper climb on snow and ice. Climbing this route requires stable snow and temperatures below freezing to ensure that the gully’s treacherous fractured rock stays frozen in place. Under the right conditions, this route is challenging and is an aesthetic line to the summit. This route climbs over 4,000 feet in just over three miles, crossing 45- to 50-degree slopes.

Nowadays, Bell Mountain is most often climbed from the west side. However, there are several more difficult routes on the peak which are seldom used. In 2019, I was discussing the peak with a daring young climber, Clint Barg, who was planning a difficult climb up the peak’s east ridge. During the conversation, I mentioned that I had first climbed the peak 39 years earlier and was considering making a 40th-Anniversary climb in 2020. Clint said, “Count me in.”

When the new year dawned, I wondered (as I do every January) if I was still capable of making long, demanding climbs. I was thankful I had committed to climb the peak with Clint because a commitment has to be honored. I asked a few friends if they wanted to join us. By the time August rolled around, Alex Feldman, Steve Grantham, Blaine Chandler and Matt Durrant had enthusiastically signed on. Additionally, fellow climber and Outdoor Idaho producer Bill Manny decided to come along and bring videographer Jay Krajic and climbing assistant Terry Lee. We had a summit party of eight and a support crew of four ready to share the pain the climb would inflict on us.

We met in Basinger Canyon on a Friday evening. Although at first a party-like atmosphere prevailed, we were all secure in our tents at an early hour. The next morning, at my insistence, we drove rough 4WD roads around the base of the peak’s west ridge to Black Creek in order to start at a higher elevation, shaving off 400 feet of elevation gain.

While I seldom climb with big groups, a large group of climbers exudes a positive, almost spiritual energy that helps pull everyone up the mountain and somehow lessens or dulls the pain. Our first task was to climb a wide, steep rib that would lead us to the ridge top meadow where I had wallowed in snow 40 years earlier. The group spread apart and came back together many times on this leg, talking, laughing, and sharing stories of past climbs. Clint, the strongest climber, ranged far ahead scouting the route.

We reached the 10,000-foot, snow-free ridge top meadow and most of us took a break. Jay, assisted by Terry, was filming on and off. Steve and Alex had also previously climbed the west ridge and the three of us, using faded memories, told the others about the route ahead. If you have climbed high enough times, you know the suffering involved is a precursor to the joy you feel when you are literally touching the sky. Taking in the view, our group was already feeling the rewards of the journey.

We climbed on. Spotting Clint near the top of the first of the ridge’s two obstacles, I wished that I was a bit younger. Speed in the mountains increases a climber’s margin of safety when bad weather threatens. We clambered on passing the first obstacle, a 200-foot cliff on its north side, without difficulty. The next obstacle was a fin-shaped stretch of ridge. The crux of crossing this terrain, at least for me, was a lack of memory about the best way to go. In the end, we crossed over the top of one section and climbed around the south side of a treacherous section on narrow ledges. Shortly after passing the obstacle, we reached the 10,800-foot spot below the west face where Dana had waited for me on my first attempt.

This tower, viewed from the east, blocks the west ridge at roughly 10,300 feet. It is most easily bypassed on its south side.

Everyone in our group was an experienced climber knowledgeable about route finding. Each of us had an idea about the best line to climb on the west face. After a short discussion, we put on our climbing helmets and started up. Clint led the way. Mountaineers confront the objective and subjective hazards that exist when climbing a mountain. Objective hazards are derived from the mountain environment and include falling rocks, falling ice, snow, altitude sickness, and adverse weather.

Subjective hazards are derived from the climber’s competence and include a climber’s errors in judgement, lack of proper planning, lack of skills and lack of proper physical conditioning. Learning how to avoid and survive these hazards must be high on a climber’s list of preparations BEFORE embarking on a mountain adventure. A climber might know how to deal with all of the hazards that they might encounter in the mountains, do everything right in response to a hazard, and still run into trouble or even die. Under some unfortunate circumstances, fate may still get you.

The peak’s west face is a series of easy-to-climb rock steps cluttered with loose rock. It is not a place where you will fall very far. Rockfall was the one hazard we had to worry about as we made our way up the face. If rockfall was going to happen, it would be caused by one of us. As experienced climbers, we minimized the danger by wearing helmets, sticking close together when possible and, when this was not possible, staying out of the fall line of climbers who were above us. In theory, these precautions work. In practice, there can always be unforeseen complications. I followed what I thought was the best line. We waited for those below us to be out of the line of fire when we were in a spot where loose rock was likely to dislodge.

Clint reached the summit first. Alex and Terry were just above me as we zig-zagged up a steep gully about a hundred feet from the top. I lightly stepped on what appeared to be a solid section of rock. Instantly, all hell broke loose. I dislodged a bushel basket-sized rock. It took off, going from zero to sixty nearly instantly. It was one of those moments when time seems to stand still. “Rock,” I screamed. In my mind, I could see the tragic headlines, “Guidebook Author Kills Outdoor Idaho Crew.” The rock careened down the gully hitting one side and then the other.

I saw Jay jump to his left. Bill ducked down behind a rock step just before the rock flew over the spot where he was standing an instant before. The rock continued its journey down the gully and then all was quiet. It was a moment for reflection and thanks as well as my apology. Climbers often ignore it but, any time you are climbing a mountain, tragedy can quickly overtake you.

We were soon all on the tiny summit. I was as elated as I was tired. A circle was completed after 40 years. My long association with the peak impacted the course of my life. The lack of available information in 1978 on Idaho’s mountains and Bell Mountain in particular was the impetus that started me on my quest to write a guidebook to Idaho Mountains. I started to collect information and, twelve years later, published the first edition. Bell Mountain also gave me a great respect for Idaho’s many remote and unknown peaks.

Next: The Toughest 11er