Mount Whitney was the first Sierra Nevada peak that I climbed (in 1972). At that time, I knew very little about the range. I made the decision to climb Mount Whitney after spotting it on a California highway map which designated the peak as the highest in the Lower 48 states. The map showed a trail leading to the summit and I thought, “Why not?” After climbing Whitney, I was hooked on the great granite range and vowed to return. Two years later, I secured a seasonal ranger position at Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. I was in “Fat City.”

Upon arriving at the Park in April 1974, I quickly used my employee discount and bought 2 books. The first book was the Mountaineers Guide to the High Sierra/A Sierra Club Totebook; the second book was the High Sierra Hiking Guide to the Mount Whitney 15-minute USGS quadrangle. This fine guidebook (still in use today) summarized my aspirations to visit every corner of the Whitney country. Unfortunately, my job was on the West Side of the Park and I was unable to use the book that year. Life and other climbing opportunities often get in the way of our dreams.

In 1991, I finally managed to put the High Sierra Guide to the Whitney quadrangle to use. I also visited this area again in 2008. The Whitney 15-minute quadrangle covers the highest portion of the Sierra Nevada including 14,000-foot peaks, deep canyons and a vast array of lakes, tarns and alpine meadows. How to see this country at its finest was a question that I mulled over for years.

I finally decided to enter the range south of Mount Whitney at the Cottonwood Lakes trailhead, cross New Army Pass into Sequoia National Park and then take a cross-country route through Rock Creek and the Crabtree Lakes drainage where we would join the John Muir Trail. From this point we would hike the JMT north to Wallace Creek, hike up Wallace Creek, cross the Sierra Crest north of Mount Russell and exit the range at Whitney Portal. Our climbing objectives along the way would include 4 Fourteeners. This route was clearly mapped out on the copy of the Whitney topographic quad that came with the High Sierra Hiking Guide.

I contacted the Inyo National Forest and was given the names of people in Lone Pine, California who offered a shuttle service. I made arrangements for our shuttle. Dana Hanson and I met our driver at Whitney Portal on September 12th and were driven to the Cottonwood Lakes trailhead. We got an early start on our ambitious journey and hiked over New Army Pass and then dropped down to Lower Soldier Lake where we set up camp. This was roughly a 10.0-mile journey. The trail east of the pass goes by many spectacular lakes. You could easily spend a week exploring the area. In 1991 (before the advent of bear canisters), the Park Service had placed steel bear boxes in many backcountry locations because of ongoing, serious problems with bears raiding hikers’ food supplies. We had the lake and the boxes to ourselves.

Looking toward New Army Pass. Mount Langley is the big peak on the right.

The East Side of New Army Pass is full of scenic terrain.

The New Army Pass trail is well constructed.

On Day 2, we set out to climb the first 14er on our list: Mount Langley (14,042 feet). Langley is the southernmost 14er in the Sierra Nevada Range. It is a big mountain that was first climbed by one of my heroes (Clarence King) in 1871. Our route ran from the lake northeast of a feature named The Major General and, from there, directly to the summit. The view north to Mount Whitney encompassed many peaks that I had yet to climb. Every summit eventually leads to another summit. We descended by hiking down the peak’s South Slopes to Army Pass (not to be confused with New Army Pass) and then back down to our camp.

Mount Langley as viewed from Mount Whitney.

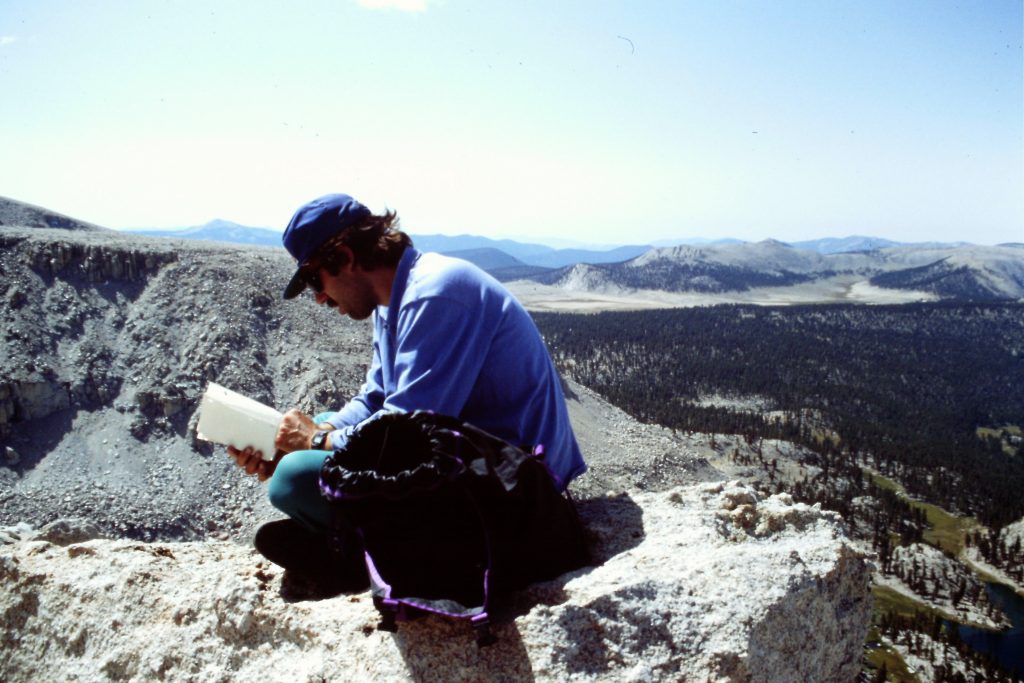

Checking out the summit register atop Mount Langley.

Mount Muir (left) and Mount Whitney (right) as viewed from Mount Langley.

Day 2 was the day that I most looked forward to undertaking when I planned the trip. Our route would proceed cross-country up Rock Creek into Mitre Basin, cross Crabtree Pass and descend to the uppermost Crabtree Lake. The going was delightful. We stopped for lunch at Sky Blue Lake and then hiked to the pass at 12,560 feet where we could take in the many peaks surrounding us and scope out our planned route to Mount Whitney. Down at the lake, we found a campsite in the boulders and enjoyed an afternoon of perfect weather. Our route covered 5.5 miles.

Looking down to the uppermost Crabtree Lake.

Climbing Mount Whitney (14,495 feet) from the Upper Crabtree Lake was our goal on Day 4. From the lake, we climbed northeast toward Discovery Pinnacle just south of where the Mount Whitney Trail crosses the Divide at Trail Crest. After a brief detour to the top of the Pinnacle, we followed the trail north to the summit of Whitney. Not much had changed on the summit in the 17 years since my first ascent. It was still Awesome with a capital “A” up there. After taking in the top of California, we walked back down the trail to Mount Muir (14,015 feet). Our route climbed up the South Face on solid granite. I am not sure we followed the route in the guidebook as it is rated Class 3 and we definitely were on Class 4 (or higher) terrain. Mount Muir has 331 feet of prominence but is dwarfed by Whitney. Our route up Mount Muir was the best climbing of the trip. Our round trip route to Whitney and friends covered about 8.5 miles.

Starting up toward Discovery Pinnacle.

Arriving at the Mount Whitney Trail at Trail Crest.

Mount Muir with Mount Whitney in the background.

Mount Muir

The Whitney Trail weaves through the rocky towers.

Climbing Mount Muir.

A little closer to the summit.

Mount Whitney as viewed from Mount Muir.

The summit of Mount Whitney.

Tulainyo Lake as viewed from Mount Whitney. The Cleaver is the sharp peak just right of center. Mount Carillon is the peak to the right of the Cleaver.

Day 5 was a transition day to get us from the Crabtree drainage to Wallace Creek via the Crabtree Ranger Station and the JMT. This 9.5 miles of hiking covered a variety of terrain from the Crabtree high country to the forest bench west of Mount Whitney. We saw only a few people during the day before finding a nice campsite along Wallace Creek.

Middle Crabtree Lake

Day 6 started out with a hiker trail that led to Wallace Lake. From Wallace Lake, our route turned south and climbed up steep slopes to Tulainyo Lake (12,822 feet). The crux of this walk was between 12,000 and 12,400 feet. Tulainyo Lake has a spectacular setting in a bowl with Mount Tunnabor to the north, the Cleaver to the east, Mount Carillon to the south east and Mount Russell to the south. From our campsite, we also had a great view west to the massive Great Western Divide across the deep Kern River Canyon. Our walk covered 6.0 miles with 2,400 feet of elevation gain.

Starting up Wallace Creek,

Wallace Creek

Looking back to Wallace Lake.

Day 7 felt like a good day for a rest. We limited our excursions to an ascent of Tunnabora Peak (13,565 feet) via its South Face, which covered about a mile round trip with roughly 700 feet of elevation gain.

Alpen glow at Tulainyo Lake.

Day 8 was the big climbing day that we rested for on Day 7. Our goal was Mount Russell (14,086 feet), the last 14er on our agenda. To climb the peak, we had to first climb to the Russell–Carillon Pass (a Class 3 endeavor) and then make our way to the base of the peak’s East Arete. In his book The High Sierra: Peaks, Passes and Trails, R.J Secor says of Mount Russell:

“This is the finest peak in the Mount Whitney region. It is high and beautiful, and none of its routes are easy.”

The East Arete Route was first climbed by Norman Clyde in 1926 and is rated Class 3. Like many California Class 3 routes, I would rate the route at Class 4. We found the climbing challenging but not difficult. It was the exposure in several spots that jack the rating up to Class 4. The route from the pass was easy to find. Once on top, we worked our way to the [higher] West Summit. Returning to the pass, we made the short hike to the summit of Mount Carillon (13,355 feet) via the its South Face, a Class 2 climb.

Mount Russell as viewed from Mount Carillon. The East Arete descends down the middle of the photo.

Starting up the East Arete of Mount Russell.

The snow on the arete was of recent origin.

A Class 4 move near the top?

Traversing to the [higher] West Summit of Mount Russell.

Dana Hansen on the summit of Mount Russell.

Mount Whitney as viewed from Mount Russell.

Lake Tulainyo as viewed from Mount Russell.

Day 9 (our final day) was going to be a bit anticlimactic as all we had to do was cross the Russell–Carillon Pass again and hike out to Whitney Portal. I thought we would find a climbers’ trail covering the entire distance but, instead, route finding became an issue as there were no cairns and an abundance of cliffs to work around. So close but so far away. After a few wrong turns, we finally found the Mount Whitney Trail and made our way to the car.

Ascending to the Russell/Carillon Pass with a full pack.

Descending to Whitney Portal.

I highly recommend this trip to anyone who enjoys off-trail travel or who wants to climb Mount Whitney in an unorthodox manner. When I followed much of this route in 2008, we ran into a lot of hikers in the Rock Creek and Crabtree drainages but we still had much of our time to ourselves. We covered 52 miles on the trip with plenty of elevation gain.

Next: Jefferies Glacier Expedition