In 1992, I was anxious to explore Alaska beyond Denali. After researching options, I signed up for an American Alpine Institute (AAI) expedition to climb peaks surrounding the Jefferies Glacier in Wrangell-Saint Elias National Park. This was the third year that the AAI organized trips to the Jefferies Glacier to attempt unclimbed peaks. While the trip’s biggest lure was the opportunity to make first ascents and see a large swath of Southeastern Alaska, the size and remoteness of this newly-designated National Park was the deciding factor in making the choice.

In 1992, I was anxious to explore Alaska beyond Denali. After researching options, I signed up for an American Alpine Institute (AAI) expedition to climb peaks surrounding the Jefferies Glacier in Wrangell-Saint Elias National Park. This was the third year that the AAI organized trips to the Jefferies Glacier to attempt unclimbed peaks. While the trip’s biggest lure was the opportunity to make first ascents and see a large swath of Southeastern Alaska, the size and remoteness of this newly-designated National Park was the deciding factor in making the choice.

The Wrangell-Saint Elias National Park is the largest U.S. National Park. It is 6 times larger than Yellowstone National Park. It is a land with thousands of peaks (most unclimbed) and massive glaciers which parent incredible braided rivers and tidewater glaciers. The park is the home of 4 mountain ranges and includes 9 of the 16 highest peaks in the United States. Beyond the major peaks like Blackburn, Bona, Sanford, Drum and Wrangell are wave after wave of peak-festooned ridges. The volcanic Wrangells are found in the Northern Interior. The Chugach Mountains are on the South Coast. The Saint Elias Mountains rise abruptly from the Gulf of Alaska to the east of the Wrangells while the Nutzotin and Mentasta Mountains form part of the Park’s North Boundary. The Wrangell-St. Elias Wilderness covers 66 percent of the Park’s terrain. It is, by far, the largest designated Wilderness in the United States.

Thanks to the nearby ocean waters, precipitation totals are impressive. As a result, the park’s mountain ranges see massive snowfall totals during the year and the Park has 60 percent of Alaska’s glacial ice. Our destination on the Jefferies Glacier was just one of the massive ice glaciers found in the park. I cannot adequately put into words the size of these glaciers. As big as the Jefferies Glacier is, the Bagley Icefield (which is just south of the Jefferies Glacier) appears to be 20 times larger. One source states that the Park’s glaciers cover more than 1,700 square miles. As with glaciers worldwide, the Wrangell-Saint Elias Glaciers are in retreat. However, in 1992, there was no evidence of global warming.

After landing in Anchorage, we met the other members of the team and our 2 guides. We soon piled into a 12-passenger van and left immediately for McCarthy, Alaska. The 4-hour ride was thrilling not only because of the spectacular scenery, but because the driver thought that the van was a sports car. The last 59 miles followed the McCarthy Road–a narrow, gravel road that begins in Chitina, Alaska and follows a former railroad route. The road actually ends 1/2 mile before McCarthy where it butts up against the Kennecott River. After many close calls, we arrived at the end of the road. We had to cross the Kennecott River and then a smaller stream using a manually-propelled cart and cable system suspended high over the river. There is now a footbridge over the river.

Crossing the Kennecott River.

McCarthy was founded as an alternative to the Kennecott Company towns and it prospered while mining activities continued. In 1992, the town was in the later stages of a renaissance but was still very much a quirky place. Think of the town in the TV show Northern Exposure. Our hosts at this point were the Saint Elias Mountain Guides, probably the biggest employer in the village. Our group set up camp on the edge of town along the river.

The Kennecott Mines ruins.

The next day, we hiked up the Root Glacier to an ice wall where we had a short ice climbing school which allowed the guides to determine the skills of the different climbers. In the afternoon, we spent our time visiting the Kennecott mining ruins. Kennecott is an abandoned mining camp located 5 miles north of McCarthy and just east of the Kennecott Glacier. It was the center of activity for several copper mines. The town and the mines are a National Historic Landmark and a monument to poor reclamation practices. In fact, there has been no reclamation of the mining debris.

On Day 3, we all loaded into a de Havilland Beaver and flew to the Ultima Thule resort on the Chitina River. Ultima Thule is a high-end backwoods resort. Upon arrival, we were told that Stephen Segal had reserved all of the facilities. We were instructed to avoid Segal and his family. We were shuttled to the far end of the runway where we set up camp. Curiosity got the better of us and we walked back toward the resort where we met Joe Runyan, an Iditarod champion. He was there with his sled dogs because Segal had hired him to take him dog sledding on a nearby glacier. This involved hauling the sleds and dogs via air to the high country.

An aerial view of McCarthy.

Flying to Ultima Thule.

The Chitina River

Part of the flight was along an impressive cliff with spectacular waterfalls tumbling down the cliffs.

On the ground at Ultima Thule. The de Havilland Beaver is a workhorse in Alaska. The planes were built after World War II and have flown ever since. This one had been rebuilt twice.

Finally, on May 20th our group loaded into 2 Cessnas. We flew to the Jefferies Glacier and set up camp. Based on observations made as we flew in, the guides decided to focus on the peaks on the North Side of the glacier. The flight in was even more spectacular than the flight from McCarthy to Ultima Thule. We landed on the Jefferies Glacier at roughly 5,600 feet. I must admit that I have had a hard time pinning down our exact location and I am not absolutely sure I have correctly identified the 2 peaks that we climbed. The guides had provisional USGS quads which I studied but when I tried to add my ascents on Lists of John, I was overwhelmed by the number of peaks on the North Side of the Jefferies Glacier. I finally located the 2 peaks of the correct elevation situated where I remember them to be.

Visiting with Joe Runyan and his sled team.

We flew in to the Jefferies Glacier in newer planes equipped with skis. The 2nd plane is in the center of this photo.

Landing on the Jefferies Glacier.

Our location was a land of almost absolute whiteness. A bit of exposed rock was present on the surrounding peaks but snow and ice dominated the terrain. The glacier was covered with fresh snow and, other than nearby ice falls dropping off the peaks, there were no visible crevasses. We dug into the glacier and used snow walls to build a storm-secure camp on a perfect day.

Digging in.

Raising the walls.

Home, Snow Home.

The next day (May 21st), we left early to climb a peak. Evening temperatures hovered around freezing, causing the snow to harden a bit. We had 2 rope teams: 4 clients on one rope and 3 clients + a guide on the other rope. Our first goal was Peak 7920. We made a long trip up the glacier and turned north, starting to gain elevation slowly at first. Our proposed route ran to a saddle east of the peak and avoided an icefall that dropped off the peak’s flanks. The last part of the route to the saddle was about 30 degrees. Our route did not cross any open crevasses. Once on the saddle, it was an easy ridge walk to the pointed summit.

Roping up for our first climb.

The route the guides chose worked up the snow ridge from bottom left to mid right and then turned toward the ridge in the background.

Traveling from camp to the base of the peak.

Gaining some elevation.

We had good snow conditions and never used our snowshoes.

Rest break

From the top of the ridge, we had a great view of Mount Saint Elias to the east.

The first ascent of Peak 7920 is completed.

We returned to camp by 12 Noon. The temperature was now tropical and keeping cool was the #1 priority. As the day wore on, clouds came in and, by early evening, it was snowing and blowing. While not a fierce storm, it continued into the next day, leaving us tent-bound on May 22nd. The low clouds and moderate wind kept us in our tents most of the day.

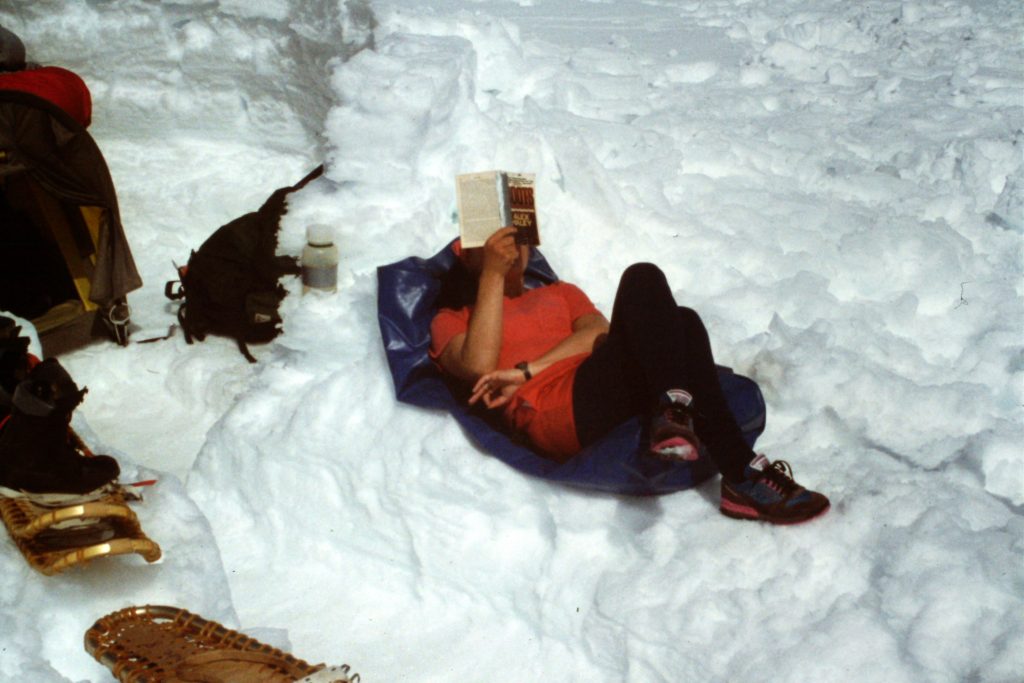

Bring a good book.

Back in camp, the afternoon was scorching hot.

Climbing in Alaska requires the ability to hang in a tent to wait out bad weather. Not everyone can handle those long days stuck in a tent.

This was our view the next day.

On May 23rd, the weather improved quickly. We got an early start and headed for our next objective–Peak 8073. This climb was a almost a duplicate of the first climb with an approach over the Jefferies Glacier and then an ascent to a saddle east of the peak. The ridge to the summit of Peak 8073 was a bit more pronounced than that for Peak 7920 but was not technically challenging. We had no encounters with crevasses.

Peak 8073

Nearing the crest of Peak 8073.

The summit of Peak 8073.

The glacier is a giant solar oven on sunny days. However, there are not many sunny days here.

In my experience, the weather is always the 800-pound Gorilla lurking during Alaskan climbing. The Gorilla struck hard on the 24th and 25th, leaving us tent-bound by a stronger storm. The storms on the Jefferies Glacier were not as intense as those I have experienced on Denali. The storms were warmer but they dumped a lot of snow.

On the 26th, we started out to climb a peak just northwest of our camp but were turned back because of deep snow, high avalanche potential and deteriorating weather. The bad weather continued throughout the 26th which was our last day on the glacier. We thought for a while that the planes would not arrive to pick us up on the 27th but the weather cleared on schedule. The planes arrived and we flew out as scheduled.

In sum, we had 4 good days and 4 bad days on the Jefferies Glacier. Unfortunately, 2 of the good days were taken up by flying in and flying out. The peaks along the Jefferies Glacier are nothing special from a technical climbing standpoint, but from a wilderness perspective, they are extraordinary. The weather will determine how much time you can spend climbing on these big ice fields. We were probably lucky to have 4 good days. Keep in mind that spending days in a tent are a large part of my Alaskan trips from Denali to the Brooks Range. Be prepared with plenty to read and have music available.

Next: Kings Peak from the East