In 1985, I attempted Denali with a group of climbers from the University of Idaho. Farther down the page, you will find my journal entries made during the climb and photos. Just below is an article that appeared in the Idaho Argonaut on June 27, 1985.

The following is a transcript of my journal from 5/14/85 to 6/3/85 plus other observations regarding my attempt to climb the highest point in North America.

My personal equipment for the Denali trip.

In April, the team traveled to Mount Hood for a shakedown climb and to practice crevasse rescue techniques.

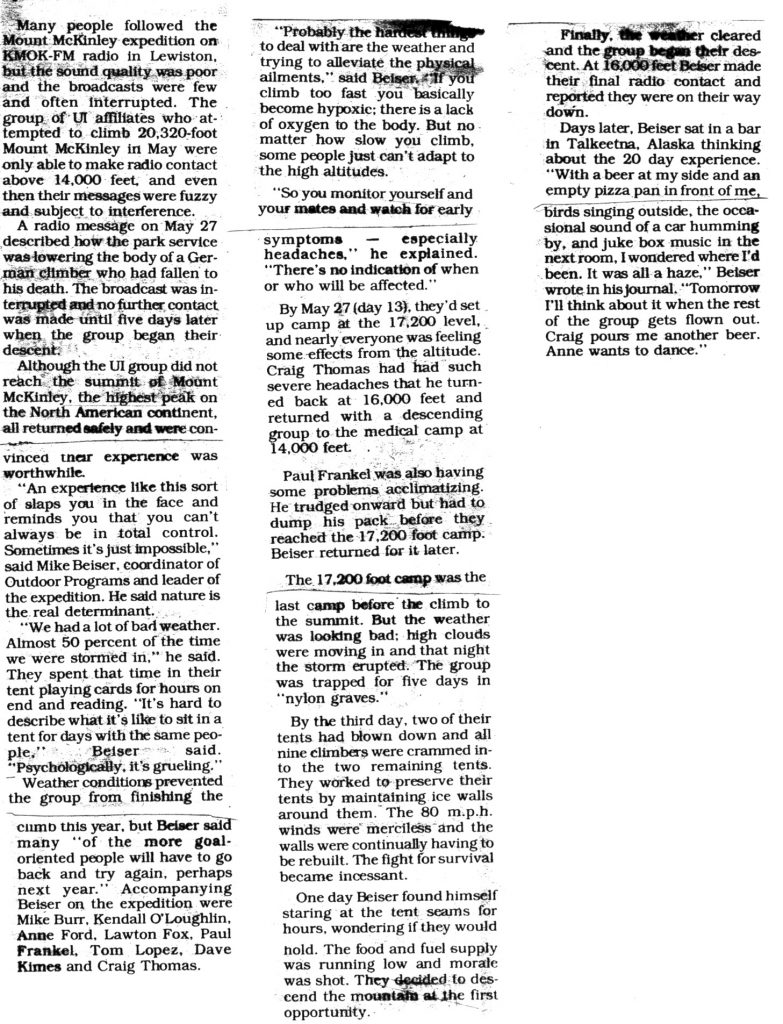

Collecting our equipment in Anchorage.

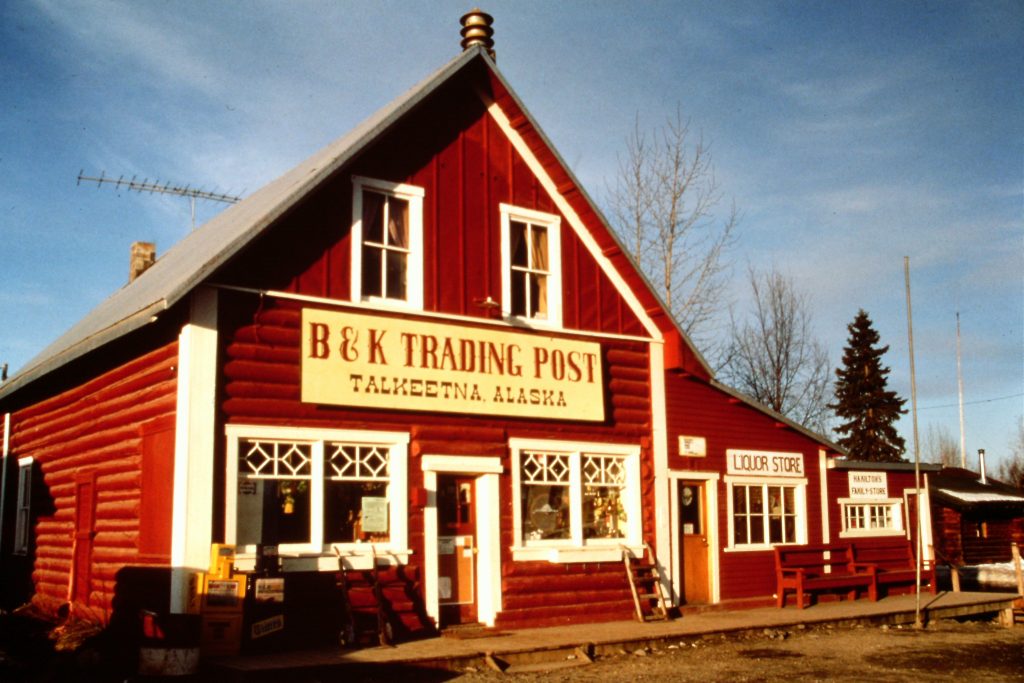

The Anchorage paper’s headline is about a climber that just died on the peak. When we got to Talkeetna, we met Mugs Stump bringing the body off the mountain and into the airport.

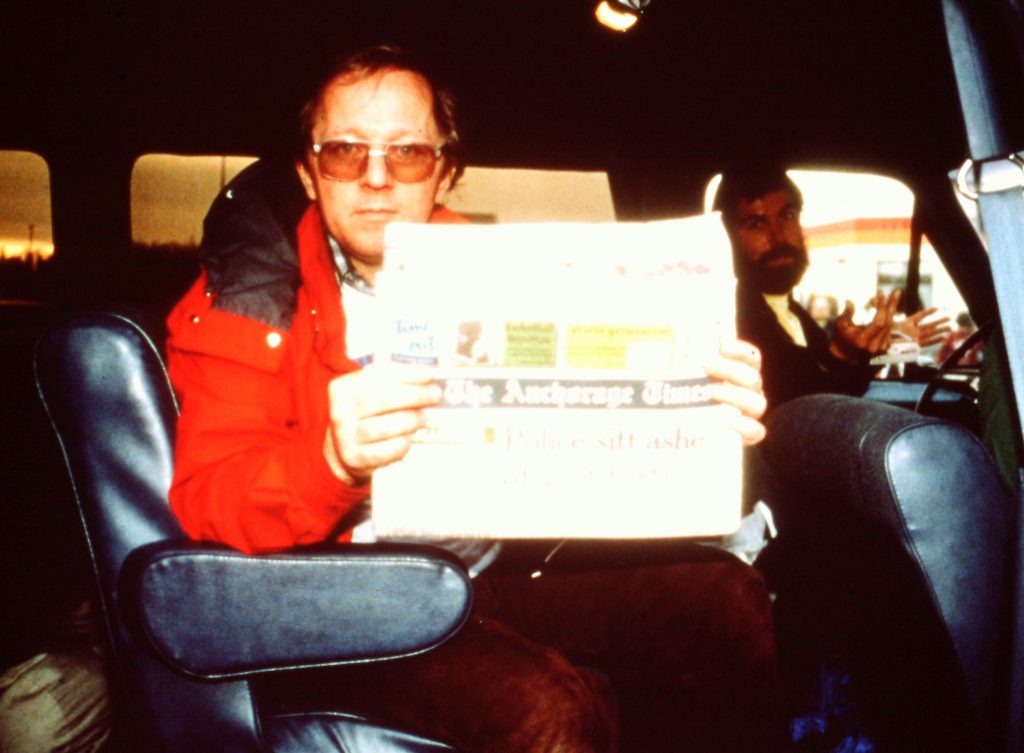

The starting point for 99% of those climbing Denali.

May 14, 1985. Today we flew to Alaska. The most dangerous part of the trip so far were 3 near misses during the drive from Moscow to Spokane and one near miss on the drive between Anchorage and Talkeetna. Very little sleep and guess what–the sun really does stay up all night.

May 15, 1985. Today we flew from Talkeetna to the Kahiltna Glacier in K2 Aviation’s ski-equipped Cessnas. The scenery is beyond description. Mountains and ice everywhere. The temperature on the glacier is 88 degrees in the shade at Kahiltna Base. We are repacking for the beginning of the climb.

Loading up to fly in.

Airborne

Denali in the distance.

Flying through the Alaska Range is an amazing experience.

Kahiltna Base is but a speck below.

Our plane is leaving us. It is time to suck it up and go.

Kahiltna Base Camp. When the sun is out, it can cook you. We left an emergency cache of food and fuel here.

When the sun is not out, you can quickly freeze.

The view from our camp.

May 16, 1985. Just back after a 9-hour carry up to 7,700 feet to our next camp. The route drops down the East Fork of the Kahiltna to the main glacier and then climbs up the glacier. Massive country. My PMA (positive mental attitude) is low because of the difficulty of the carry. We pulled loaded sleds the whole way (over 100 pounds). It snowed all day. We took turns breaking trail. If it is so difficult to move at this elevation, will I be in trouble at higher elevations? It is so easy to doubt oneself when the going gets tough. The weather continues to deteriorate. It is still snowing and the visibility is down to a very short distance. At least it’s cool today.

We had bad weather all of the time that we were below 11,000 feet.

We encountered our first crevasse field while moving food up the glacier.

The main Kahiltna Glacier is huge by any standard of measurement.

Ann Ford. How did she put up with us? She was tough!

Mike Burr

Dave Kines

Mike Beiser was expedition leader. He climbed the Cassin Ridge one year earlier.

Craig Thomas

Paul Frankel

Lawton Fox was my tent mate for the trip. He was an ancient 41 years old at the time. I think of that now and laugh.

Pinned down by weather at our 7,700-foot camp. We were well dug in.

May 17, 1985. Yesterday’s snowstorm has continued into today. We now have upwards of 3 feet of new snow and it’s still snowing. We have moved from base camp up to the next camp. We left a cache of food at base camp. The move took 5 hours because we again had to break trail the entire distance. Kendall left the climb today. He was obviously psyched out by everything. He might have been saved by good weather but I doubt it. When we arrived at Talkeetna, the charter service was bringing out a dead climber which shocked Kendall more than the rest of us. Then with the difficulty of yesterday’s carry, he must have just decided that it was more than he wanted to deal with. He left in a healthy condition. Now we are a team of 8 climbers. I felt as good today as I felt bad yesterday. Funny what a difference a day can make.

May 18, 1985. Saturday–the storm persists. SNOW. A steady and slow snowfall with only an occasional light wind and low visibility. The temperature is 26 degrees. I didn’t wear sunglasses yesterday because it was overcast and the glasses kept fogging up. Today my eyes are extremely tired and my right eye is injured due to overexposure–not snow blindness but still a lesson learned. The eye hurts a lot. Its amazing just how potent the diffused light of the storm actually is. It will damage your eyes and burn your skin. After a lot of effort, all of my clothes are dried out and that makes me feel a lot happier. Just surviving in this environment is difficult. A lot of adjustments are necessary, staying alive is a chore, eating is a chore, shitting is a chore. So far I’m adjusting well enough to everything except for the continuous daylight, which makes sleeping difficult. The storm has limited visibility. Even though we are halfway up an immense canyon, we have yet to see it.

May 19, 1985. Sunday. The 4-day storm finally ended this morning around 10:00AM but not before the temperature dropped to 11 degrees and the camp was drifted in. The sun is out and it is beautiful. We have decided to stay put today in hopes that a descending party will break a trail for us through the deep powder. The sun has improved everyone’s spirits and we are ready to go. My eye is better today. I wore a patch on it for the last 2 days and I think I will leave it on today. Now that it is clear, we can see the immensity of the mountains that tower up all around us. Hunter, Foraker, Crossen, Kahiltna Dome, Mount Francis and others are all crowned with flowing glaciers and protected by formidable walls. Today alone is worth the price of admission. We saw one large avalanche come down this afternoon. Later in the day, the wind came up and the temperature is now at 9 degrees. 3 parties have descended so tomorrow we can move up to 9,000-10,000 feet using the trail they broke. I’m having no problem getting adjusted to the cold and I’m looking forward to the hard day ahead.

May 20, 1985. Monday–a killer day. We pulled all of our gear, packs and sleds (120+ pounds) up the mountain. There was a packed trail but just off to the sides, the snow was deep and soft. Consequently, the sleds kept sliding off the trail and turning over and over again. At times, the wind blew like hell and the route climbed up Ski Hill and was the steepest terrain so far–extra steep considering the loads we pulled. We are camped at 9,000 feet and are dug into a steep slope. The view is of Mount Hunter; its incredible slopes are very impressive. The Kahiltna Glacier stretches out below us for miles and, for the first time, we can see the tundra out beyond the mountains. 6 degrees out and no wind. Our food is good but too heavy. We are still pulling around 400 pounds of food. Pulling the sleds isn’t too bad when the snow conditions allow easy going. Tomorrow we go up again…. and the next day and the next day and ….

Ski Hill is the steepest section of the Kahiltna that the route crosses.

It is a tough push. We were behind schedule so we carried everything we had up it. Roughly 130 pounds for each of us.

Just about up.

We stopped at 9,000 feet and built a camp.

Mount Hunter as viewed from our 9,000-foot camp.

May 21, 1985. Tuesday. One full week on the mountain. Time does not compute here due to the continuous daylight, the total glum of the storm days, and the endless work needed to climb. Time simply doesn’t mean the same thing that it would back home. What still does have meaning are the endless hours pulling the sled and hauling a heavy pack. Today we carried full loads up to 11,000 feet from 9,000 feet and then returned to 9,500 feet and carried up partial loads back up to 11,000 feet. Tired, but I did well. We have now reached the climbing portion of the route and will not use our skis again until we are ready to return to base camp. The view is, as always, spectacular. Tomorrow, we carry to 13,000 feet. The weather is holding and has been really fine since the storm broke. The temperature has been livable. It is amazing how easy it has been to adjust to the cold when its 13 degrees outside and not much warmer in the tent. I can sit here and write very comfortably—not even in my sleeping bag. I was often colder than this last Winter in my house. Goodnight–11:05PM.

Our 11,000-foot camp.

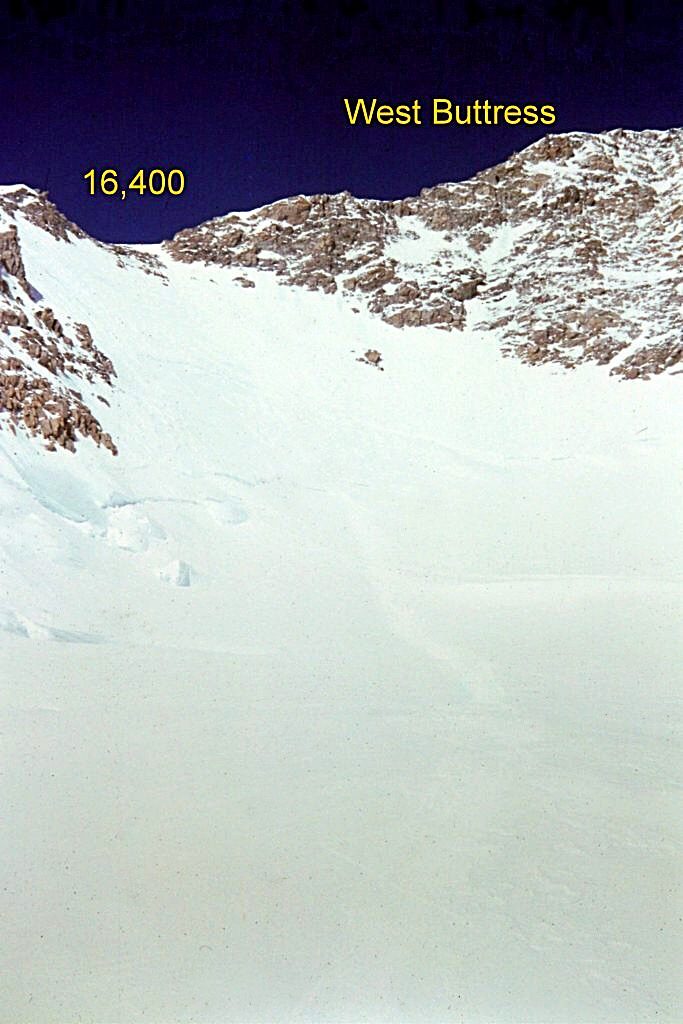

Most climbers leave their skis at 11,000 feet as the terrain above is much steeper and the snow is usually hard enough to cross on foot. This photo is looking up the first headwall at the base of the West Buttress.

May 22, 1985. Today we carried heavy loads up to 13,300 feet. The view continues to grow. Tomorrow we hope to get up to 14,000 feet. Each day is a lot of hard work, but the long run of good weather makes life bearable. Even when the air is cold, the sun will keep you warm. I’m tired but persevering. We are now climbing and our goal is coming closer and closer. We only need to hang in there and we will make it.

Climbing up the headwall which is a little over 1,000 feet high.

Nearing the top of the first headwall.

At 12,200 feet looking south.

Looking toward Windy Corner.

Two climbers at Windy Corner.

May 23, 1985. Thursday. We are finally at 14,300 feet at the base of Denali and the West Buttress. The weather looks as though it might change. We still need to return to 13,300 feet to pick a food and fuel cache. For the first time on the trip, we had to dig out a camp because there were no abandoned camps at this highly-used location. Digging at this elevation was hard work. This 14,300 foot-camp is definitely a scene. Lots of climbers from lots of different countries. The medical camp is a fair sized installation also. The headwall looms, forbiddingly above us. Very impressive and very steep. This is the highest I’ve ever camped. So far I’ve had very little trouble with the elevation–only slight headaches.

May 24, 1985. Friday. The weather has improved–it’s hot again. Today we brought our cache up to 14,300 feet. I‘ve been sleeping poorly since we arrived at this camp. It’s probably a combination of exhaustion, altitude, worry, etc. Tomorrow we carry up to 16,000 feet!

Settled in at our 14,200-foot camp in Genet Basin. We engaged in the never-ending job of melting snow for water.

Denali is on the right. The 17,300-foot camp and the end of the West Buttress is on the left.

May 25, 1985. DIRTY-—everything is dirty and impossible to clean. Today we made it to 16,450 feet and left a cache. Carry high, sleep low. The headwall is steep. We gained over 2,000 feet in a little less than a mile. The last 800 feet was secured by a tangle of fixed ropes which offered a slight feeling of safety. The headwall takes this route out of the walk-up category. I had no problem with the altitude today although I couldn’t go very fast. Some of the team had severe headaches. As a group, we are running low on aspirin. I still have enough. The weather changed today with clouds coming in from below and eventually reaching 16,000 feet. The clouds dumped light snow but most of the day we were above the disturbance. The temperature last night was 6 degrees which is the coldest we have had so far. The weather has been much more moderate than I ever expected.

The best team I have climbed with. We all contributed to planning and preparation, climbed Mount Hood together and practiced together. Left to right: Craig Thomas, Dave Kimes, Ann Ford, Tom Lopez, Mike Beiser, Lauton Fox, Paul Franke and Mike Burr.

May 26, 1985. We stayed at 14,300 feet today to help acclimatize. Craig has symptoms of AMS and went to the medical camp today for a diagnosis. The clouds rolled in again today around noon and now it is warm (38 degrees) and snowing. Tomorrow we plan on moving to 17,300 feet which is going to be the longest day yet. We could make the summit in 2 days if the weather holds. I hope so. I’m well adjusted to this ordeal-—better than I would have thought possible, but I am getting ready for it to be over. I want a salad, a shower, etc.

May 27, 1985. 17,200 feet. A long and hard climb of 3,000 feet. Craig dropped out today because of AMS and Paul is borderline. The rest of us are tired and digging a camp was very difficult. At this elevation, we mostly dug out very compacted snow bordering on ice. Just 3,000 feet above us is the summit–about 6 hours of moderate climbing. The weather looks as though it will change but we are hoping for one more good day. Too tired to write more.

Looking up at the headwall from our 14,200-foot camp.

Climbing up the lower headwall. Camp is in the background.

Climbing up the fixed ropes.

The fixed ropes were probably put in earlier by guided groups and left for all to use. Who knows how much damage the sun and storms have done to the ropes.

The headwall is steep for the final 800 feet. If you fall, you will not stop.

Resting at the bergshrund midway up the headwall.

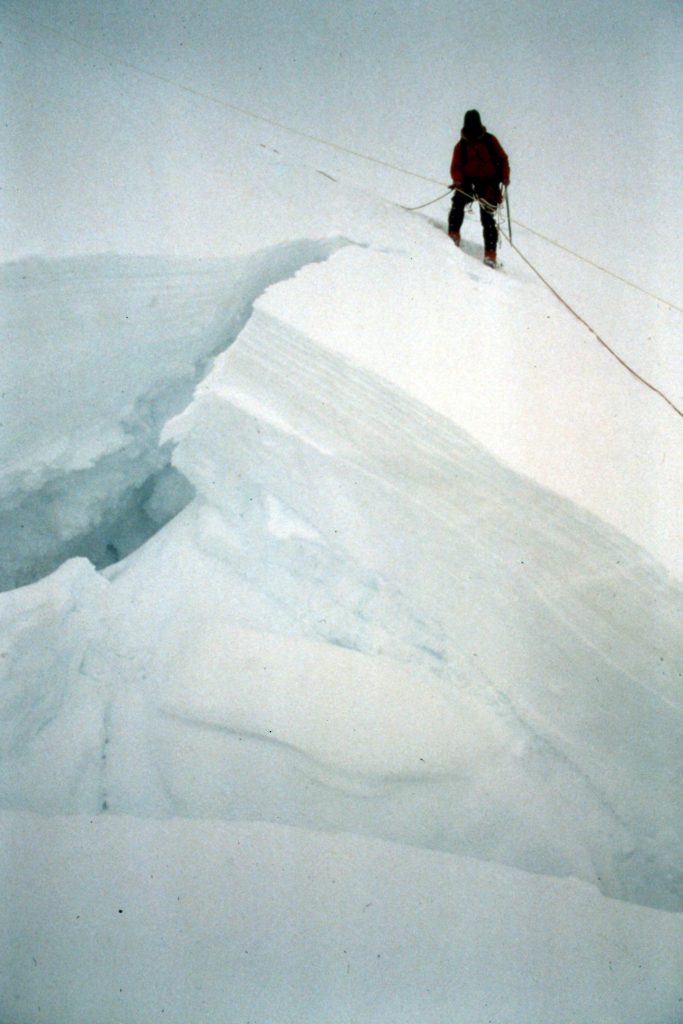

Starting up the West Buttress above 16,400 feet.

May 28, 1985. Tuesday. A storm came in last night. The weather is not too bad yet but everything is socked in. Climbing when the weather this unsettled is out of the question at this elevation. I only slept about 3 hours last night. I also felt like I was getting sick and the change of the weather added to my concerns. The beginning of this storm makes it likely that we will be on the mountain for at least one more week. The possibility of getting altitude sickness scares me. I thought my symptoms might be the first signs of an altitude problem. However, since I’ve never had an altitude problem before whenever I feel bad, I think it could possibly be an altitude problem. I have nothing to measure the problem against. I think I am truly sick of being pinned in camp again–my PMA is low today.

We are camped in a somewhat protected spot but the West Buttress behind us is as exposed as any ridge. If strong winds come up, we will be trapped here for as long as the wind blows. Yesterday’s climb up the West Buttress, although exhausting, was fabulous. This mountain is so big that it is difficult to describe. Above 14,000 feet, distance can only be experienced in terms of hours. 3 1/2 hours for one mile and 2,000 feet with heavy loads. 5 hours for one mile and 1,000 feet. I’ve put in a lot of effort to make it to the top of Denali. 4 months of running, 402 miles, $1,500 in expenses, 2 weeks of back-breaking effort to get myself and equipment up to 17,200 feet. I want this summit. Still!

This is the cloud formation we saw as we built our camp at 17,300 feet. This is not a good sign.

Food. I estimate is that we brought over 700 pounds of food to Denali and we have been letting it dictate how we live ever since. The problem is that we needed a lot of calories to do the work and to keep us warm. Add to this that we are all relatively cash-poor climbers and we had to use heavy food because it is cheaper. Additionally, we brought a lot of food that we have not used. Almost all of our cheese went bad and the salami is questionable. I think I’ve learned a lot that will help for planning future trips. Our food is tasty. There is always something good to eat. The essential food plan was good; it need only be refined.

Tent bound at 17,300 feet. At first, the storm was only an annoyance.

Day 2 of the storm is beginning to cause us some concern.

Most of the time, the almost impossible task of climbing this mountain has kept my mind too burdened to spend much time thinking about civilization. That is a good thing. Cuts on fingers do not heal in this environment. Instead they seem to get bigger and more painful. 3:31 PM–I still do not feel good. I can’t sleep. No fever. Pulse varies from 90-114 while I’m resting. The sky has cleared at our elevation but down below everything is socked in. I’ve been in the tent for all but 5 minutes today. 8 degrees outside earlier today but it’ comfortable in the tent. I was a little cold last night when I first went to bed. The sleeping bags get damp and then freeze on the outside cover but somehow they keep us warm. My personal assessment of myself on this trip, as of now, is as follows. I’ve done things that were much harder than I have ever done before. I’ve kept in a good frame of mind most of the time and haven’t lost my temper. I’ve been rational at all times. It’s very slow going in the tent today.

May 29, 1985. Storm bound again today. I have a terrible headache and have had it since early last night. Tylenol helped me sleep but wore off this morning. I took a Diamox this morning which helps increase the oxygen saturation in the blood. As a result, I feel much better now but I would have been happier if I had lost the headache without taking the Diamox. A park climbing ranger is also camped up here–Scott Gill, a University of Idaho graduate. He came up to help lower a dead climber down the Exit Couloir. He has also diagnosed a number of climbers in other groups with cases of HAPE and HACE. Today there is a climber camped by us with severe HACE. He has been put on oxygen but they still need to get him down in the face of this storm. Scott says this guy could easily become the third fatality since we arrived in the park. I do not want to die up here or while climbing any mountain. But it is better than staying at home waiting to die. What a dilemma.

Every once in a while, we hear large avalanches roaring off the nearby slopes but the visibility is so low we can’t see them. The ridge between our camp and the headwall is serrated and steep and would be difficult to traverse in this storm. So, in effect, we are trapped with most of our high-altitude food in a cache 800 feet below us on the ridge.

May 30, 1985. Around 4:00AM, a tremendous wind storm hit the mountain and our tent is in peril of being destroyed. The snow walls that surround the tents are are slowly disintegrating in this wind. The wind is blowing ice crystals at high velocity and this is sandblasting our walls. I wish we had dug deeper and built better walls when the storm was less ferocious. For the first time on the trip, I was scared this morning when it looked like the tent was doomed. We managed to build up the wall a bit. Last night the temperature dropped to at least -18 degrees and right now it is only up to zero. Snow is constantly filtering into the tent and coating everything. I’m chilly and hungry because we can’t cook with the wind blowing so hard. The water bottles are freezing up. Fortunately, we have plenty of snack food to eat. Its so cold out that exposed flesh will freeze in no time at all. Going to the bathroom can be life threatening. When the storm breaks we have 2 options: go up or go down. I still want to make the top. We are so close but my endurance is being lowered by this storm. Getting back to civilization is tempting after spending the last 60 hours in this tent with no end in sight.

May 31, 1985. The storm continues. Lawton and I were forced to abandon our tent this morning as the wind had finally eroded the protective snow walls away. We flattened the tent to keep the wind from destroying it. Lawton moved into Mike, Paul and Ann’s tent. I’m now crammed into a small tent with Dave, Paul and Mike. I can‘t lay down but fortunately I am warm. The storm outside shows no signs of ending and we are almost out of food and have only 2 standing tents. Every 10 minutes or so, an extra strong gust hits the tent, giving us something to think about.

For the first time, we are wondering out loud what it’s going to take to survive. Everyone has given up on making the top and now only think about getting back alive. Outside the tent, every movement is painful and very difficult. You can’t see, the wind can easily knock you down, and the wind chill factor must be incredibly low. The barometer continues to fall. On the whole, the team is doing well and has made the best of the situation. Still we have all been tested by the wind.

June 2, 1985. 12:53AM. We abandon the climb. The winds slacked off enough yesterday morning to allow us to safely descend. It was an easy decision as we were out of food, low on fuel and mentally exhausted. Even more importantly, the ranger received a weather report which calls for more snow. We just arrived back at 11,000 feet after a long day retreating. Our cache at this spot was marked by an 8-foot high flag. When we arrived only 1 foot of the pole was still above the surface. A big dig was in order to get to our food and fuel.

Lawton and my tent after the storm broke. We had dug deeply into the side hill and put up big walls around us. Nevertheless, the storm wind eventually overcame our efforts.

The weather is still shitty but at this elevation, it is much more moderate than up high. Later, after sleeping, we will ski out to Kahiltna Base and hopefully get a flight home. Rumor has it that there are over 80 people waiting to fly out. 11:46PM: At Kahiltna Base after a long, long day. Weather is shitty. We are hopeful that a plane will be able to get in and pull us out of here tomorrow. 3 of the group are already out–lucky SOBs. Today was extra long because Mike Burr was on our rope and on snowshoes while Lawton and I were on skis. We had to wait for him rather than skiing out, letting gravity do the work. What a way to travel.

June 3, 1985. Day 19 on the mountain and the weather looks lousy (upgraded from shitty). There is a low ceiling with a wind blowing down the glacier and a wet snow falling. It looks bad for a flight out.

EPILOGUE: Later on June 3rd, K2 flew in and took us out. There were a few tense moments because of the bad weather, but it was wonderful to return to Talkeetna which was snow covered when we left and was now in full and vivid Spring. Leaves and grass never looked so inviting to me. The trip was more than I ever could have hoped for and I hope to get another chance to climb Denali.

Next: In Grizzly Country