Article Index

This article was originally published in the September 2022 issue of Idaho Magazine Vol. 21, No 12.

Stapled to a sign at the trailhead to Targhee Peak in the Henrys Lake Range, a large note handwritten in red ink read:“caution. One mile up the trail and near the trail is the carcass of a dead horse. grizzly bears may be guarding or consuming the remains.” Targhee Peak is among Idaho’s most picturesque mountains, its bold southwest face crowned by a ring of ragged cliffs. Located just north of Island Park and west of Yellowstone National Park, it’s one of those peaks that aesthetically pull me toward the summit. When I first looked at it, I wanted to climb it. But after reading this note, I suddenly didn’t feel so eager.

Stapled to a sign at the trailhead to Targhee Peak in the Henrys Lake Range, a large note handwritten in red ink read:“caution. One mile up the trail and near the trail is the carcass of a dead horse. grizzly bears may be guarding or consuming the remains.” Targhee Peak is among Idaho’s most picturesque mountains, its bold southwest face crowned by a ring of ragged cliffs. Located just north of Island Park and west of Yellowstone National Park, it’s one of those peaks that aesthetically pull me toward the summit. When I first looked at it, I wanted to climb it. But after reading this note, I suddenly didn’t feel so eager.

It was a perfect late-summer day in 1985 at Island Park: sunny, fifty degrees and not a cloud in the sky—a day that promised a great climbing experience. The mosquitoes had come and gone. Dana Hanson and I were visiting our friends Karin and Scott Bates, who both worked for the US Forest Service. The day’s agenda for Scott, Dana, and me was to climb the peak, and after breakfast we had driven to the trailhead. On the way, we had excitedly discussed the route and commented on our luck at having such exceptional weather. We unloaded, put on our packs, and walked to the register box, where we saw the grizzly warning mounted on a large Forest Service informational sign.

Grizzly bears have long stalked the deeper recesses of my mind. I was quite young the first time I read of these fearsome bears in a book about the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Those explorers, who endowed the bears with the “grizzly”moniker, had more than one run-in with them. They were among the first to write about the bears and are probably as responsible as anyone for documenting its fierce predilections. Before Lewis and Clark confronted their first grizzly, Native Americans had warned them about the dangerous animals.

Lewis and his companions soon confirmed firsthand that the bears were not only dangerous but also nearly indestructible. In a May 14, 1805 entry in the Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Lewis wrote about one unforgettable encounter, from which members of the Corps of Discovery were lucky to escape unharmed.

In the evening the men in two of the rear canoes discovered a large brown bear lying in the open grounds about three hundred paces from the river, and six of them went out to attack him, all good hunters. They took the advantage of a small eminence which concealed them and got within forty paces of him unperceived. Two of them reserved their fires, as had been previously concerted. The four others fired nearly at the same time and put each his bullet through him, two of the balls passed through the bulk of both lobes of his lungs. In an instant this monster ran at them with open mouth. The two who had reserved their fires discharged their pieces at him as he came towards them, both of them struck him, one only slightly and the other fortunately broke his shoulder, this however, retarded his motion for a moment only. The men, unable to reload their guns, took to flight. The bear pursued and had very nearly overtaken them before they reached the river. Two of the party betook themselves to a canoe and the others separated and concealed themselves among the willows, reloaded their pieces, each discharged his piece at him as they had an opportunity. They struck him several times again but the guns served only to direct the bear to them. In this manner he pursued two of them separately so close that they were obliged to throw aside their guns and pouches and throw themselves into the river, altho’ the bank was nearly twenty feet perpendicular. So enraged was this animal that he plunged into the river only a few feet behind the second man he had compelled to take refuge in the water, when one of those who still remained on shore shot him through the head and finally killed him. They then took him on shore and when they butchered him they found eight balls had passed through him in different directions.

In June 1805, Lewis was alone scouting. He shot a buffalo and then almost immediately spotted a grizzly bear charging towards him. His unloaded, single-shot rifle was of no use, so heran and jumped in the river. Fortunately, the bear stopped. As I recall, Lewis slept with his gun from that point onward. When you read something like that at ten years old, it sticks with you.

My first visit to grizzly habit was in Montana in 1971. The first night I actually spent under the stars in grizzly country was at Elizabeth Lake in Glacier National Park. The year before, a grizzly had killed a woman at Elizabeth Lake—a fact every camper at the lake felt compelled to tell us. I fully expected a grizzly bear to kill me. I survived that night as well as the next three nights, albeit with very little sleep. While I lived to tell about the experience, my fear of the great bears never really waned.

I’m not a wildlife biologist but I’ve learned enough about the bears over the years, rightly or wrongly, to question my judgment every time I’ve ventured into grizzly habitat. The experts will tell you that grizzly bears try to avoid humans. I take some comfort in that. Nevertheless, grizzly bears will eat almost anything, from nuts to fruit to roots and, of course,salmon, rodents, sheep, deer, and cows. Why not people? After all, if a grizzly needs to eat up to ninety pounds of food in a day, how picky can it be?

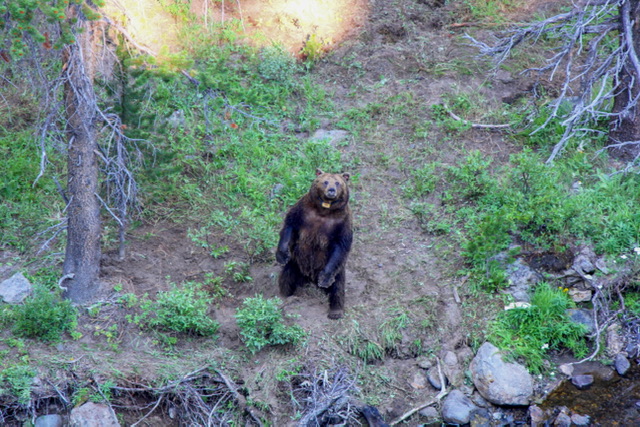

The grizzly bear sits at the top of the food chain. Its scientific name is Ursus arctos horribilis, which doesn’t describe a docile demeanor. The name was earned from the bear’s physical characteristics. Grizzlies can weigh more than eight hundred pounds and a particularly large bear might be eight feet long. The beast has fearsome claws, can run up to thirty-five miles per hour, and can smell food from miles away. A grizzly might live up to thirty years and can accumulate a great deal of common sense in that period of time. From my perspective, the fact that mother grizzlies are very protective of their cubs is another thing to worry about. An estimated six hundred to one thousand grizzlies live in the 22.5-million-acre Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, which includes Island Park and Targhee Peak.

“Well,” I thought after reading the red-letter warning on the sign, “so much for a perfect day.” Everything I knew about grizzlies swirled around in my head. Scott, who had a useless small-caliber pistol strapped to his hip, didn’t seem concerned. He worked in the area’s forests nearly every day. Although Dana and I were both hesitant, we had our hearts set on reaching the top of Targhee Peak. So, relying on Scott’s confidence, we started out cautiously, talking loudly and wishing we had bear bells strapped to our packs.

The first mile-and–a-half passed quickly and uneventfully. We didn’t spot a dead horse, smell a carcass, or encounter a grizzly. Relieved, we continued up the trail to the point where we had to leave it. Although it eventually would lead to nearly the top of the peak, we were now feeling adventurous. We decided that rather than following the long circuitous trail, we would climb directly up the peak’s southwest face. This was a much shorter route, which we hoped would involve an interesting scramble through the series of scenic cliffs that capped the face.

To reach the base of the face, we had to leave the trail and descend down to and then cross the West Fork of Targhee Creek. The timber was thick and we had to guess at the best place to cross the creek. We picked a spot that looked promising and descended to the creek, only to find a small, deep, vertically walled gorge blocking our way. After looking at our topographic map, we decided the mostly likely crossing would be farther upstream.

We started walking again and soon entered a young lodgepole forest interspersed with small meadows. These trees were small and the sunlight was nearly unimpeded. After goinga short distance we reached the middle of a meadow and Scott’s dog, Cedar, growled. I looked up and at the far edge of the meadow, maybe a hundred feet away, a young grizzly was ambling toward us. Cedar barked. The bear stood up on its hind legs. Scott grabbed Cedar’s collar and pulled his pistol out of its holster.

“Back away,” he whispered.

I was third in line at this point. Scott moved past me away from the bear. Dana followed. I stood looking at the bear. It was my first ursus horribilus sighting, and I felt both awe and fear. My mind flashed on scenes from the movie Night of the Grizzly and on the “Bear Country” brochure that was handed out by the National Park Service at nearby Yellowstone National Park. On my first visit to the park, I had read the most relevant parts of that brochure over and over. A major piece of advice was: “do not run!” So I stood still while my companions retreated. I looked at the closest trees, thinking maybe I could climb to safety. The tallest one was only ten feet high—tree-climbing was not an option.

Somewhere behind me, Cedar barked furiously. The grizzly dropped to all fours and charged toward me. Advice from the Park Service brochure ran through my mind: “Most bear attacks result from surprise encounters. Some bears will bluff their way out of a threatening situation by charging, then veering off or stopping abruptly. Bear experts generally recommend standing still until the bear stops and then slowly backing away.”

I stood my ground. To this day, I don’t know if I stood there because of what I read in the brochure or because I was too terrified to move. What to do? Once again came the Park Service’s advice: “If you are attacked, drop to the ground and lie completely flat on your stomach. Spread your legs slightly and clasp your hands over the back of your neck. Do not move until you are certain the bear has left.”

Can you imagine playing dead while a grizzly is biting or clawing you? I couldn’t. While all these thoughts raced through my head in real time, Cedar broke away from Scott’s grip and came charging past me. The grizzly stopped on a dime, turned,and quickly disappeared into the trees at the far end of the meadow. Cedar streaked into the trees, hot on the bear’s heels.

Scott and Dana came up next to me, both yelling, “Cedar! No, Cedar!” over and over as the dog’s barking faded away. We looked at each other, at a loss as to how we could save Cedar. Then the barking started again, but this time it was getting louder.

“Darn, the bear is coming back,” I said. “Darn” was not exactly the expletive I actually blurted but you get the idea. This time, the bear was chasing Cedar. Dana and Scott retreated again. I stood still. Cedar shot past me. The grizzly stopped twenty-five feet from us. It rose up on its hind legs. We stared at each other. It was a time of reckoning, for the bear and for the rest of us. Maybe the bear was also scared, or maybe it had read the Park Service brochure. Suddenly, it dropped to all fours, turned, and ambled away.

We regrouped, relieved and elated. After our adrenaline rush dissipated, we reviewed our near miss and what to do next. A decision was made, and we set off to climb the peak. Finding the route through the cliffs was challenging and fun. The view from the summit was amazing. Yet after our grizzly encounter, the day’s climbing was hardly what we would remember about that day.

Next: Glacier Peak – The Long and Winding Route