I have been fortunate enough to spend a great deal of time in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Long before I first visited the range, I was enthralled with the mystique created by writers like John Muir and Clarence King. My first foray into the range was a hike up Mount Whitney in 1972. I had little experience at that time, but one trip above treeline and I was hooked on those granite mountains. I worked for Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks in 1974 and 1976 and have taken many long backpack trips through the range over the years. My 2008 trip with Laurie Durocher was one of the most rewarding of these trips.

I have been fortunate enough to spend a great deal of time in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Long before I first visited the range, I was enthralled with the mystique created by writers like John Muir and Clarence King. My first foray into the range was a hike up Mount Whitney in 1972. I had little experience at that time, but one trip above treeline and I was hooked on those granite mountains. I worked for Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks in 1974 and 1976 and have taken many long backpack trips through the range over the years. My 2008 trip with Laurie Durocher was one of the most rewarding of these trips.

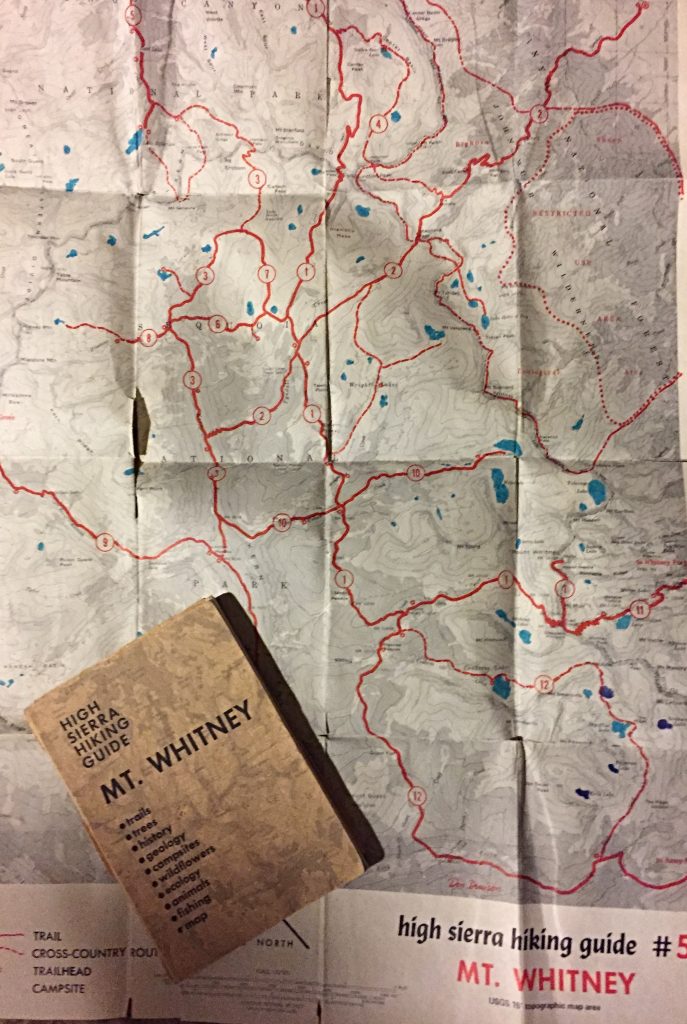

The first Sierra Nevada guidebook I bought was a High Sierra Hiking Guide. The book covered the Mount Whitney 15-minute USGS quadrangle. This guide and many more like it were published by Wilderness Press. These fine guidebooks are still usable today. Each pocket-sized book came with a copy of the topographic quad covered by the text with all the trails, cross-country routes and distances marked on the map. This 2008 trip was my 2nd foray over New Army Pass. The route we followed is a classic and is well worth repeating.

Laurie and I made arrangements with a Lone Pine, California resident coincidentally named Cal for a shuttle. Cal was 100% cowboy and had worked as a wrangler and extra in Hollywood in his younger years. He provided us with interesting conversation as he drove us between the Shepherd Pass trailhead and the New Army Pass trailhead. Cal unloaded us at the 10,000-foot New Army Pass trailhead and wished us luck.

The first step.

There are lots of lakes along our route.

New Army Pass is the next trailed pass south of the Mount Whitney Portal and Trail Crest. It is not nearly as popular and offers an alternative approach into John Muir’s “High Sierra.” We planned our first day to cover only 6 miles and thus give us a chance to acclimatize to the altitude. Nevertheless, we gained more than 2,000 vertical feet before reaching our camp at the north end of Long Lake. Starting at 10,000 feet and then sleeping at 12,000 feet on the first day is not ideal but, other than a restless sleep, we came through just fine.

Our camp at Long Lake.

Bear containers are required almost everywhere in the Sierra Nevada. They make packing much harder and are not light.

The highest lake before reaching the pass.

On Day 2, we followed a good trail up over 12,200-foot New Army Pass, which is the boundary of Sequoia National Park. From the pass, we descended to Soldier Lake. We left the trail at this lake and scrambled cross-country over a small divide, dropping into Mitre Basin. The cross-country route through Mitre Basin and Crabtree Lakes Basin is a popular route and we saw 6 other hikers along the way. At nearly the top of Mitre Basin, we reached Sky Blue Lake which lives up to its name in every respect. Our route covered 7 miles. We had the lake to ourselves.

New Army Pass

Soldier Lake

Our camp at Sky Blue Lake.

The next day, we were beset by unexpected rainy weather with occasional thunder and lightning. So we converted Day 3 into a rest day to further acclimatize and enjoy the setting.

On Day 4, we tackled the trail-less pass between Mitre Basin and Crabtree Lakes Basin. The 2-mile hike from Sky Blue Lake to the pass is strenuous and the route finding is challenging. You must cross granite shelves and grass- and flower-covered ledges and circle around lakes and ponds, all the while dealing with considerable ups and downs to reach the pass. I rate the route we followed as Class 3.

Looking toward Mount Whitney.

Looking down to the uppermost Crabtree Lake.

Descending from the pass, the route crosses steep, loose talus. There was a hiker’s trail in the talus in many places. At the Upper Crabtree Lake, the angle eased and we found ourselves walking on glacially-polished granite, following a stream as it cascaded down to the next lake. Wildflowers and views of the rock, the water and a building storm called for frequent photo stops.

Looking back at the pass.

Looking down the Crabtree drainage.

Crossing the granite floor.

Just as we reached treeline, the building storm broke in a tremendous explosion of lightning, thunder, water and hail. For the next 2 hours, the storm roared in the Crabtree drainage. At one point, there was 3 inches of hail covering the ground. It took over an hour to find a spot flat enough for a camp. The tent went up in the middle of the tempest. We did our best to keep dry and warm. As suddenly as the storm swept in, it was gone. By 5:30PM, the sun was out and, by sunset, everything was dry.

On Day 5, we hiked out of the Crabtree Lake Basin and north past Crabtree Meadows Ranger Station to find the John Muir Trail (JMT) at the point where the trail turns east to climb to Trail Crest and Mount Whitney. At the trail junction, we found a sign and plastic bags for collecting your human waste and directions that anyone following the trail up to Mount Whitney was required to shit in a bag and carry it out. We continued north, now following the JMT to Wallace Creek. We encountered a lot of hikers finishing their JMT trek. All were anxious to reach Whitney’s summit and hurried onward, immune to the incredible scenery. Wallace Creek is a large drainage. We hiked up the drainage a half-mile and had the entire area to ourselves.

Be sure to pick up your excrement bag before climbing Mount Whitney.

Looking west from the JMT to the Great Western Divide.

On Day 6, we continued north along the JMT to Tyndall Creek, where we once again left the busy trail to head northwest to a small, unnamed lake at over 11,000 feet. Despite a location only 2 miles from the JMT, the lake showed little evidence of prior use. A long afternoon turned into a spectacular evening of moonlight and then a dark sky with billions of stars.

Looking northwest across the Kern River Canyon to the Great Western Divide.

Heading north on the JMT.

Our final campsite.

On Day 7, we originally planned to hike over Shepherd Pass and drop down to Anvil Camp. However, when we arrived at our proposed camping spot, we found it infested with large, aggressive mosquitoes and decided to press on. This turned into our longest day, as our route took us from over 12,000 feet to the desert below and our trailhead in 13.5 miles. The highlight or should I say lowlight of this day’s hike was a 1,500-foot ascent midway through our descent. This climb takes you from one drainage to another. For years, I had dreamed of hiking up this route to Shepherd Pass. After hiking down this trail, I was glad that I had never ascended it.

Heading east toward Shepherd Pass.

Dropping down to the Owens Valley.

The alpine vegetation is giving way to desert flora.

After a long, long descent, the trail climbs over the saddle to the west of this rock.

Water froze at our last camp. When we reached the truck, it was 97 degrees. We were ready for a shower and hot meal.

Next: Say It Ain’t So: 2009 Denali Expedition