March 15, 1976: 7:00AM. My thermometer reads 19 degrees. Light is filtering through the cracks in the walls of the hut. My 2 companions are still sound asleep. We’ve now been in the Talamanca Range for a week. Never in my wildest dreams would I have visualized mountains like this in Costa Rica.

In writing this entry in my journal, I was feeling sad that our trip was ending but I was also elated by the success of our trip. We had spent the last 6 days scouting Parque Nacional Chirripo (Chirripo National Park) and every day proved rewarding.

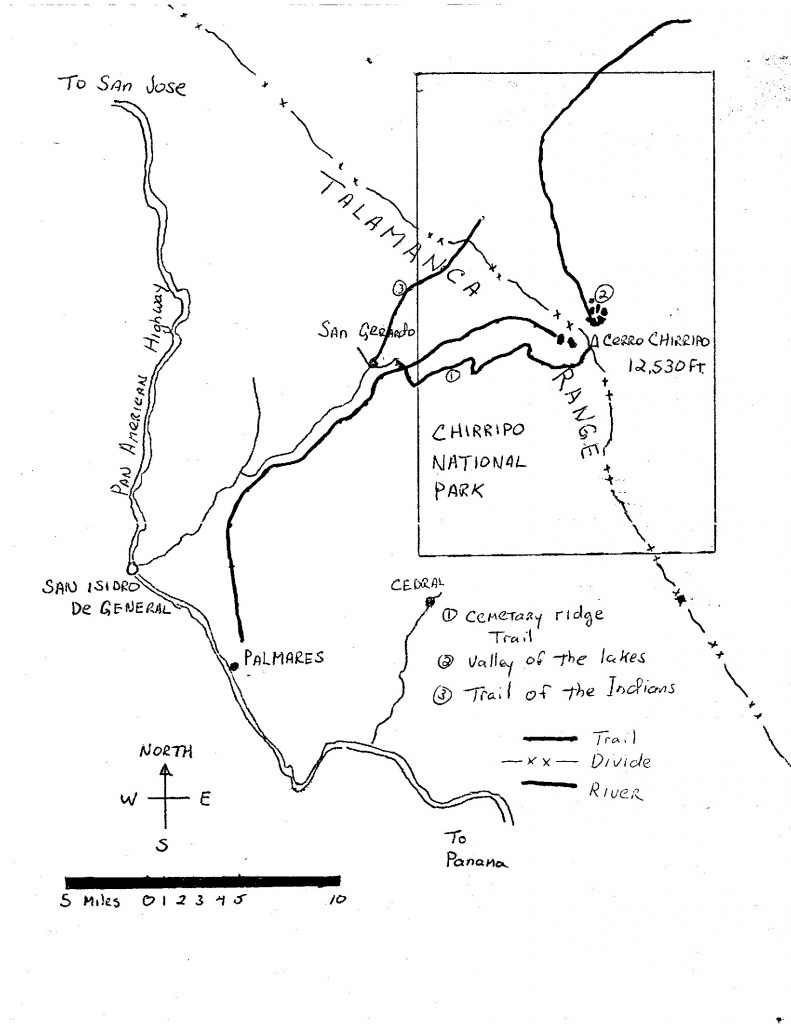

In 1975, the progressive and democratic Costa Rican Government declared 300 square miles surrounding Cerro Chirripo (a 12,530-foot peak) a National Park. This area represents the highest sections of the Talamanca Mountain Range. When we visited these mountains in 1976, Chirripo was a National Park in name only. Severe budget shortages had forced the Costa Rican Park Service to concentrate its efforts on more endangered parks. Fortunately, this is a remote area that needs little protection at present.

Costa Rica is a Central American Republic of 19,000 square miles with a population of a little over 2 million. Northern and Central Costa Rica is dominated by a series of volcanoes. The 3 largest volcanoes: Poas (8,362 feet), Barbs (8,940 feet) and Irazu (11,322 feet) surround the Capital (San Jose). These volcanoes have given Costa Rica the title “The Switzerland of Central America.” However, the largest mountains are in the sparsely-populated southern section of the country. Rising out of the steaming Central American jungles, the Talamanca Range climbs to over 12,000 feet. The range runs over 200 miles through Southern Costa Rica and Northern Panama. High , wild and remote, the Talamancas provide a striking contrast to the coastal jungles and the deforested hills of Northern Costa Rica.

Central America is a land bridge between North America and South America. It is a meeting ground for plant and animal species. Phil Defrieze, a scientist with the National Museum of Costa Rica, feels that when studies are completed in the Talamanca Range, many new species of plants and insects will be identified. These new species will be crosses between Northern and Southern species. The Costa Rican Park Service has made big strides since its creation 7 years ago. Even so, many Costa Rican Parks have been severely damaged by squatters who attempt to open the land for agriculture. Unlike the United States, Costa Rica is a developing country with different priorities. Many times, national parks take a backseat to more basic human needs.

I became interested in the Talamancas through my job working as a Peace Corps advisor to the Costa Rican Park Service. I decided to visit this national park after learning that no park service employee had ever visited the park. Several days were spent searching for people in San Jose who had first-hand knowledge of the region. It seems that few Costa Ricans know about the Talamancas. Traditionally, native Indians have hunted in the mountains from their homes in the foothills but other visitors to the area are few. Eventually, I was able to find and question several who had some information about the area. I learned that recently the Costa Rican Alpine Club had constructed a trail into Chirripo National Park. I recruited 2 other Peace Corps volunteers (Randy and Tom), gathered equipment and we were ready to depart.

San Jose is typical of Central American cities–noisy, crowded and polluted. So it was with anticipation of high adventure that we gathered our equipment and left by bus at 3:30AM for the mountains. San Isidro de General, 120 miles south of San Jose, was the jumping-off point for our trip. Our bus arrived at San Isidro at 7:00AM. We left Tom to watch our equipment. Randy went off to hire a truck to take us up to San Gerardo and the trailhead while I went to find a pulperia. A pulperia is the Costa Rican version of a general store. When I returned with my purchases, I found Randy surrounded by 5 Costa Ricans (or “Ticos” as they liked to be called) all vying to be our chauffeur. After 15 minutes of haggling and shouting, we hired a small Datsun pickup for 120 colones or about $10.

By 10:00AM, we were crowded into the pickup and bouncing along towards the trailhead. It is 18 miles of bumpy dusty road from San Isidro to San Gerado. Tom had lost a coin flip and was sampling most of the dust as he rode behind the cab. The Talamanca Range is a formidable barrier. Several roads have been extended into the foothills but there are no routes crossing the mountains east to west. After 7 miles, the road dropped down off a ridge to the River Chirripo which flows to the Pacific. Our driver talked constantly about the virtues of his truck and occasionally pointed out the local points of interest. In many places, the road was narrow and precarious but this did not bother us until we approached a bridge over a small stream. The bridge was partially washed out and looked as though it might fall into the stream at any minute. I was a little apprehensive and suggested that it might be wise if I got out to test the bridge on foot. Before I could get the door open our driver gunned the motor, slipped the clutch and shot across.

We reached the end of the road in another 5 miles. I was thankful to be safely on my own two feet again. The little village of San Gerado has a school, a pulperia and several houses. The elevation is 4,000 feet. This is where the trail starts and it was well over 100 degrees when we started up the trail at 2:00 in the afternoon. The trail climbs steeply for the first 1,000 feet through hot, dry cattle pastures. March is at the end of the dry season and, at this time of the year, all of the farmers burn their fields to prepare them for the new growing season. As a result, the smoke was so thick that we were unable to see the towering peaks that were our destination. In the east, these agricultural fires have sometimes gotten out of hand and have burned large areas of forest. Just as the heat was about to overcome us, we entered the forest.

The vegetation zones of the Talamanca Range are the Tierra Caliertefi, the Tierra Templado, the Tierra Fria and the Paramo. The Tierra Caliente or “hot land“ consists of the coastal jungles and rises from sea level to 2,500 feet. The Tierra Templada or “temperate land” runs up to 5,500 feet and supports a variety of less-tropical type plants. The Tierra Fria or “cold land” lies above this up to treeline at 11,800 feet. The Paramo exists only above 11,800 feet and is a high barren land swept by strong, cold winds which are usually accompanied by cold drizzle. Like Alpine areas the world over, only the hardiest of plants can live in this region. There are differences in the vegetation depending on which side of the mountain you are on. On the wet Caribbean slopes, a dense rain forest grows while on the drier Pacific slopes, we found deciduous forest which supports occasional savannas. Wildlife consists of many species of birds and mammals. The largest animal is the seldom-seen jaguar.

We spent our first night at 8,000 feet elevation. Our camp was located in the ruins of an old hut which occupied a knob on the steep Cemetery Ridge. All afternoon we had hiked up this steep, forested ridge. The newness of this large hardwood forest with its many strange trees and plants was exciting. At sometime in the past, a fire had burned across the knob and now acres of raspberries grew in place of the trees. When we awoke early the next morning, we were treated to our first view of the high peaks silhouetted in the morning light.

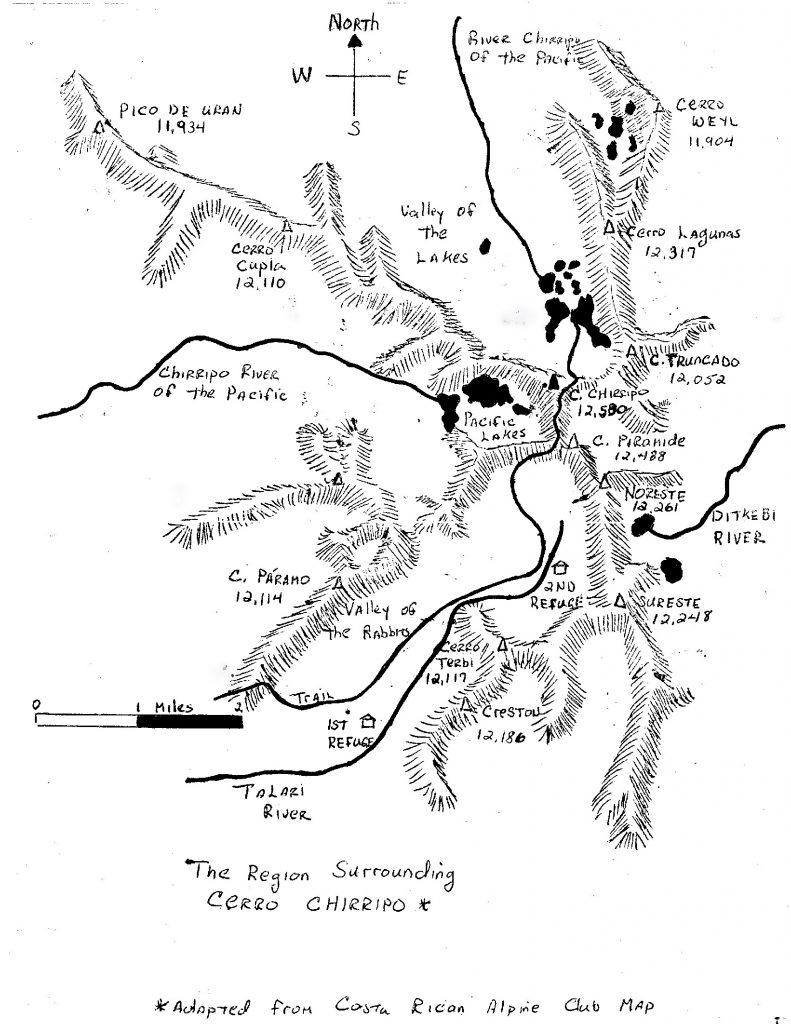

In the morning, it took us several hours to reached a large cave and a spring where we ate lunch and explored the forest. Another 2 steep miles from the cave, the forest began to thin out. The trees became smaller and then eventually became stunted and deformed. Even though they were hardwoods, their twisted trunks reminded me of Alpine fir in Oregon. Crossing over a ridge, we were confronted by our first view of the Paramo and the high Valley of the Rabbits. Below us was the 1st of 2 primitive refuges which were constructed by the Alpine Club.

We decided to continued on to the higher 2nd refuge. The trail weaved up and down, back and forth and around many obstacles until it reached the 2nd refuge. The sun was already setting when we started cooking dinner. Our bodies, which had acclimatized to the warmer environs of Costa Rica, shivered with cold as the temperature dropped to 20 degrees.

March 10th: Only 8 degrees north of the Equator and its colder than hell.

Inside the refuge, previous groups had left mementos of their visits. Sheets of paper recorded the names of people who had reached the roof of Costa Rica. On the 3rd day, we left for the summit of Cerro Chirripo in an early morning mist. Sheaves of ice still clung to the largest grasses surrounding the hut. The trail leading toward the peak was moderate at first as it climbed toward the pass below Chirripo. We could see the peak’s pyramid-shaped summit ahead, coming to a small point of rock and grass. From the pass, we worked our way up the last 600 steep feet to the summit.

The summit view was spectacular. To the east, we saw the Atlantic Ocean. To the south stretches Panama. To the west, we spotted the Pacific Ocean. To the north was Nicaragua.

March 11th: I’m sitting on top of Costa Rica. For miles, the land drops away from me. At 7AM, the light mist cleared and we started receiving the benefits of the sun. The first 2 days through the forest were interesting and different. The lush forest was strange to me; the variety of vegetation so alien to the pine forests of the American West. And now, sitting on top of it all–the windswept Paramo, the forest and the jungle. The power of this environment is invigorating.

After descending to the pass, we hiked down to the Valley of the Lakes. We found these lakes to be very beautiful. The lakes are shallow with crystal-clear water. Each morning, they were covered by a thin layer of ice.

Costa Rica suffers in many regions from water shortages because as the population has increased, the forested watersheds have been deforested for agricultural purposes. The Talamanca Range represents Costa Rica’s last region of protected watershed. Yet today there are movements afoot to open up the land to homesteaders and lumber companies. The Costa Rican Government has estimated that at the present rate of deforestation, the country will be without forest cover in just 20 years. This is in sharp contrast to the situation when Christopher Columbus discovered the country in 1502. At that time, 97% of Costa Rica was forested. Today (1975), only 35% of the land remains with tree cover and many watersheds have been destroyed.

That night as we sat around our mountain stove, we came to the conclusion that if Costa Rica is to avoid environmental catastrophe, the Talamanca Range must be preserved. The Costa Ricans have already made great strides toward protecting their environment but they have found it difficult to explain the need for national parks and forest reserves to poor farmers.

I awoke about 11AM and was astonished to see a comet with its fiery tail glowing in the sky. I woke up Randy and Tom so that they could see the show. I never learned the name of the comet. The next day we continued to explore the park’s upper reaches. The park has all that Costa Rica has to offer in the way of mountaineering. Although all of the summits have been reached, there are many rock walls of from 500 to 1,000 feet which offer some technical climbing opportunities. Cerros Lagunas and Truncado are the most impressive peaks above the Valley of the Lakes. In the south, Cerro Terbi and Pica Sureste are the highest summits. The majority of the summits from the Park boundary to the Panama border are unexplored. The entire Atlantic slope is virgin territory protected by dense rain forest. Several grassy savannas have no recorded visits by man.

March 13th: 20 degrees again last night but dawn has brought clear blue skies and finally no wind. The sun is very strong and, no matter how much suntan lotion we use, it still burns us. The sun has brought warmth back to my body. An eagle circles above my head. He has flown so close that I wonder if I am near a nest? It is so quiet up here that the absence of sound hurts my ears.

On the next to last day of our trip, we returned to the 2nd refuge. Upon reaching the refuge, we met a Mexican hiker and his guide from the Alpine Club. They had just finished climbing Chirripo and were preparing to leave. We had a lively discussion about whose country had the nicest mountains. Eventually, a consensus was reached. We decided that only the physical qualities of mountains can be compared, while the beauty and the intangible qualities of mountains cannot be compared. Each mountain has its own soul–its own hidden secrets.

For me, the Talamancas have shown their secret side. They are not the highest mountains I have climbed nor are they the most exotic. They were unexpectedly beautiful and thoroughly remote. I will never forget them.

March 16th: After a long walk and a slow ride in a jeep, we got back to San Isidro. I‘ll be back in San Jose tomorrow and I already miss the Talamancas.

2016 Postscript:

Later in 1976, a wildfire originated from a burning field and spread into the park. The fire burned a large portion of the park including over 80% of the high Paramo. Fire-fighting capabilities in Costa Rica were almost non-existent. Reportedly, the vegetation made a good comeback, although some areas will never recover to their original state. Scientist have speculated that fire may be the key ingredient in maintaining the Paramo in its treeless condition. In many ways, the Chirripo Region typifies all of the natural beauty and all of the human problems present in Central America. Poor economic conditions and growing population pressures make preservation of natural areas like Chirripo difficult for local environmentalists to justify. With the help of international conservation organizations and the Peace Corps, Costa Rica has struggled for environmental stability.

Chirripo National Park is located east of San Isidro de General in Southern Costa Rica. To reach the park, take the Pan American Highway through Cartago to San Isidro. There is bus service available from San Jose. Drive east to San Gerardo along a road that will destroy passenger cars. It is best to hire a truck and a driver to haul you between the 2 villages. San Gerardo is a little village with no services, so stock up on supplies before leaving San Isidro. The trail starts at San Gerardo and you will find that the villagers are helpful if you get lost. The trail climbs a ridge for roughly 10 miles and 8,000 feet, from San Gerardo to treeline. The Costa Rican dry season reaches its peak in February and March, making this the best time to visit the area.

The Costa Rican Park Service’s web page for the park: http://www.costarica-nationalparks.com/chirriponationalpark.html

NEXT: Two Sierra Nevada Traverses, 1976, California