Mountaineers commonly refer to information as “beta.” This term comes from rock climbers more so than from hikers/scramblers but is useful in all mountaineering contexts. Beta is critical when undertaking a mountain climb, particularly if much of the climb is off-trail. But even trail hikers should be concerned about beta: road conditions, trail conditions, etc. This essay delves into the realities of good beta, bad beta, and no (i.e., nonexistent) beta.

Good Beta

Good Beta is accurate, complete information. It is up-to-date and thorough. Good beta comes in the form of books, websites, maps, trip reports, online forums, word of mouth, etc. It focuses on access details, climbing routes, terrain, and the mountain itself. It does NOT focus on a climber’s self-promotion in a trip report, for example. Good beta shows currently-maintained roads and trails. With respect to topographic maps, it shows contour lines (typically in 40-foot intervals). LiDAR is improving the accuracy of peak elevations and prominence statistics. This is especially important for peaks with no previously measured high point.

Forest service MVUMs (motorized vehicle use maps) are the most up-to-date indications of the roads (or ATV/MC trails) that currently exist (good beta). However, the same MVUMs show no topography or current road/trail conditions (nonexistent beta). Forest service maps generally show accurate road and trail data but that is not always the case, so be careful. However, a forest service map (or trail maps from DeLorme, National Geographic/Trails Illustrated, and Adventure Maps) or typically covers a much broader area than a USGS topo map and, as a result, fails to show the terrain contours and other natural features (e.g., peaks, ridge points, mountain lakes) in as much detail if at all.

Bad Beta

Bad Beta is inaccurate or incomplete information. Maps can show roads/trails that no longer exist (inaccurate) or fail to show old roads/trails (or sometimes new roads/trails) that do exist (incomplete). Maps may also mis-label roads/trails, mis-position them, show segments of them that no longer exist, or fail to show segments of them that do exist. USGS topo maps are typically 30-40 years old and have such “bad beta.” I have found many instances where a sub-standard, 4WD road (as shown on maps) is actually a maintained and quite drivable affair.

Those same USGS topo maps show old roads/trails that still DO exist and are useful to hikers/climbers (good beta). Those old roads/trails may no longer show up on current National Forest maps or MVUMs. MVUMS typically fail to show topography with contour lines (a big drawback). National Forest maps often use large contour intervals (e.g., 100-200 feet) and/or show contour lines on a scale that is almost useless if navigating off-trail terrain. That’s bad beta.

Land management maps and National Forest/BLM maps may have inaccuracies with respect to private/public land areas. There are a surprising number of cases (in Idaho) where there is private land (e.g., parcels or cabins) within BLM land or National Forest land. Sometimes these patches of private land are shown on maps but sometimes they are not. Given Idaho’s strict Trespassing Laws, this can be a real problem. In addition, a National Forest map may infer that the Forest Service (or BLM) has an easement across private land. That may or may not be true. Landowners in Idaho are increasingly closing down access to National Forest and BLM land with gated, posted road closures. For example, the North Fork Little Timber Creek Road is inaccessible due to a private land closure gate. However, even current maps show that road as publicly accessible.

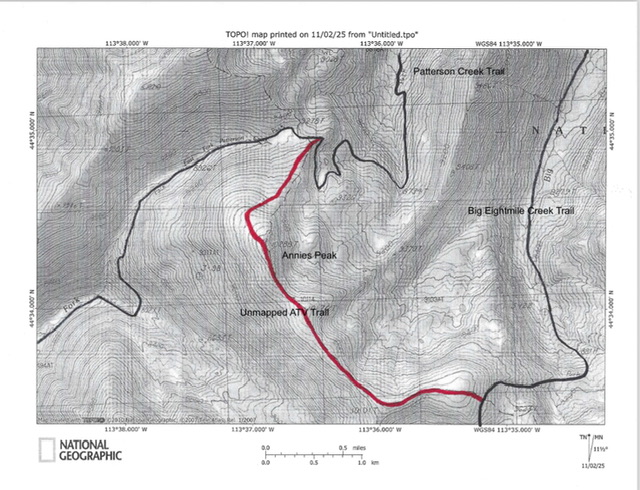

Existing Forest Service Trails (in black) and Missing Forest Service ATV Trail (in red) on the USGS topo map. The missing trail that comes up over Annies Peak is an illustration of a map error.

Another source of bad beta is with respect to a mountain peak’s high point, elevation, and prominence. LOJ may place the high point of a mountain in an arbitrary spot (e.g., the middle of the highest area above the highest contour line) but that is not the actual high point of the mountain. You must search for the high point yourself which may be easy or somewhat difficult. In addition, for many of Idaho’s peaks, LOJ uses interpolated peak elevations and saddles, which creates only estimations of a peak’s actual elevation and prominence. USGS topo maps sometimes show spurious final contour lines on the summit or summit area where no such hump exists. Maps also occasionally have typographical errors (wrong elevation figures, mis-labeled creeks, etc.). LOJ often relies on USGS topo maps with such errors.

Media

Books, websites, or trip reports that provide a few cryptic sentences about a route constitute incomplete information and are bad beta. I find information like that pretty much useless. The trip report may say nothing about the type of terrain or route obstructions (like cliff faces, rocky towers, or patches of impenetrable willows/aspens/forest). The trip report (or website) may fail to include a Class rating (e.g., Class 3, Class 4) for the specific route It may fail to give an indication of the time required to complete the route. In addition, there are cases where a climber simply inaccurately states a route direction (e.g., “go west” instead of the actual direction which is “go east”).

Electronic Beta

Nowadays, climbers increasingly rely solely on electronic devices like smartphones and GPS devices. I caution you to have a backup plan. What if you drop your device, damage it, and make it inoperable? What if the batteries die out? What if there is an unexpected manufacturing problem with the device that can’t be rectified by putting in new batteries? GPS devices, National Forest software, and GPS devices suffer from the same problems as maps: contour intervals that hide dangerous terrain, difficult creek crossings that look easy on a map, terrain that is steep and tiresome, etc.

Changing Terrain Conditions

Terrain conditions are perhaps the biggest source of bad beta. Areas of forested terrain (on a USGS map, a National Forest map, or on LOJ) might not be forested anymore. The area might be a burn area (common in the Salmon River Mountains) or an area of vast pine-bark beetle kill (standing, dead trees). Or it might be an area that was mowed down by a recent avalanche. Areas of non-forested terrain might now have pines or aspens growing in them. Even if the forested/non-forested demarcation is correct on the map, the map says nothing about the type of open terrain that you must deal with. But that is a “no beta” issue which I will discuss later.

Generally speaking, I would much prefer to have “no beta” than “bad beta.” At least with no beta, you have no illusions. You know that you will have to figure it out. With bad beta, you may be counting on a road or trail and find out that it doesn’t exist, requiring you to make “on the fly” adjustments to your climbing route. And that can be problematic.

No Beta

No Beta means that you are on your own. Figure it out for yourself. For off-trail mountain climbers, “no beta” is pretty common. Here are some examples. No updates on current road conditions or trail conditions. Yes, you will find this out if you visit a local Forest Service or BLM office and ask. “Well, we don’t know that but here is an MVUM. Good luck!” Consequently, I don’t bother to ask anymore. I just investigate the road, drive it (if possible), and figure it out. And I provide my updated “access” findings on the IACG website for peaks that I climb (good beta).

Are there downed trees across the road, making it impassable? Is the road badly rutted or washed out in sections? Another problem is a dirt road that becomes deep mud with a quick thunderstorm while you are parked miles up that road and are now stranded. Current road conditions MATTER (and what those road conditions could quickly become with heavy rain), particularly in Idaho.

A National Forest (or BLM) trail can present the same problem. The trail may show up on a map but might not have been maintained for years. Even if the trail is maintained, has it been cleared of trees, branches, and rockfall this year or not? Trails often aren’t “cleared” until late June or early July. You just don’t know until you hike the trail or old 2-track road. What about rivers/creeks/streams? In most cases, maps fail to show how deep/wide a creek is. And, the difficulty of fording a creek may vary significantly, depending on the time of year that you plan to cross it (e.g., Spring versus Fall).

I have found creeks in the Snake River Mountains to be raging torrents in early June and bone dry in September. A route that is impassable in June may become quite easy in September. Is there an easy way to cross the creek on fallen logs? Maps are mum on this. Is the creek drainage clogged with dense willows or other brush? With no beta, you may have difficulty in crossing the creek or you may carry a pole and sandals when you don’t need them.

What about open, non-forested terrain? Here is where “no beta” is rampant. With the exception of some “willowed” areas along creek drainages shown on a USGS topo map, the open terrain can be a wide variety of possibilities: easy field grass or tundra, stable gravel or scree, and cattle/game trails. It can also be loose scree/gravel, boulders, rocky outcrops, cliff bands, steep face rock, thick sagebrush and other scrub, or new growth aspens. I encountered some areas of impenetrable brush in the Boise Mountains in Spring 2025, for example. The pine forest may have spread over the past 30-40 years and the non-forested area may now be pine forest. The 40-foot contour intervals that are typical on USGS topo maps can hide steep sections or rock or scrub. They can even hide impassable cliff bands of 6-10 feet in height. Worse yet, the 80-foot contour intervals on some USGS quadrangles (e.g., in the Big Hole Mountains) hide even moresins.

What about forested terrain? Maps fail to show the thickness of the forest. Sometimes, it is easy, gapped pines. At other times, the “forest” is simply a few scattered pines on a ridge line. And at other times, the forest is thick pines with aspens and mountain mahogany mixed in. What about the understory? Sometimes, it is easy pine duff with minimal understory. At other times, it is thick veg or brush that is almost impenetrable. Idaho’s Panhandle and the Big Hole/Snake River Mountains are two areas that have sections of simply impenetrable forest. Maps fail to show the extensive burn areas in Idaho. These burn areas can be very time-consuming and, sometimes, impenetrable (e.g., the Iron Lake area in the Eastern Salmons). Sometimes, avalanche debris blocks a trail or an off-trail route. Maps fail to show avalanche debris. Being off-trail, you must deal with these realities and suffer accordingly. Good beta from a thorough trip report can help resolve these uncertainties.

What about other dangers like rattlesnakes (e.g., on the Snake River Plain) or grizzly bears (e.g., near the borders with Wyoming or Montana)? You may have no beta on such matters. I stumbled up some large bear beds (in a grassy field) in Summer 2025 that I never expected to find in that area. And then there is the always unpredictable weather in the mountains. Maps and GPS devices won’t help you overcome that problem.

Summary and Conclusions

Mountaineering in Idaho is increasingly challenging. Maps are becoming more inaccurate and outdated. Private landowners are prohibiting entry into National Forest and BLM land in more and more areas. Terrain conditions are constantly changing. My advice is simple. Carry multiple maps (USGS topo map, National Forest map, trail map), a compass, a GPS device, and perhaps an altimeter or smart phone. Be able to read a map and use a compass intelligently. Be able to assess and navigate all kinds of unfriendly terrain. Have a good memory and take notes along the way so that you can navigate the descent back to your vehicle. Be prepared to deal with rugged roads and trails that are not maintained properly. Seek out good beta, avoid bad beta, and deal with nonexistent beta.

Wear good footwear. Trail hiking shoes don’t typically cut it when in off-trail terrain in Idaho. You run a much higher risk of a knee, foot, or ankle injury in lighter shoes. I typically wear backpacking boots for off-terrain travel in Idaho. Be physically fit. Work on your aerobic training in the off-season and keep your legs strong. It’s always a good idea to have a climbing partner with you in case something goes wrong. Carry a PLB and/or a smart phone that communicates with satellites (iPhone 14 or newer). Don’t blindly rely on a GPS device or Google Maps. They don’t show the vagaries of actual terrain and hidden issues like cliff bands (even within forests).

All of that being said, Idaho’s mountains are an enjoyable place to recreate. I have spent almost 1,000 days of hiking/climbing in Idaho over the past 20+ years and do not regret it. Yes, the loose rock, private land issues, and changeable weather can be a headache. But standing atop a quiet summit and enjoying magnificent views never gets boring. Enjoy!