Elevation: 11,936 ft

Prominence: 476

Climbing and access information for this peak is on Page 274 of the book. Also see Wes Collin’s article on The Lost River Traverse in the Climbing History Section.

Contents:

1) Standard Route details

2) North Face Direct Route by Wes Collins and Bob Boyles

3) Grand Central Couloir Route by Joe Crane

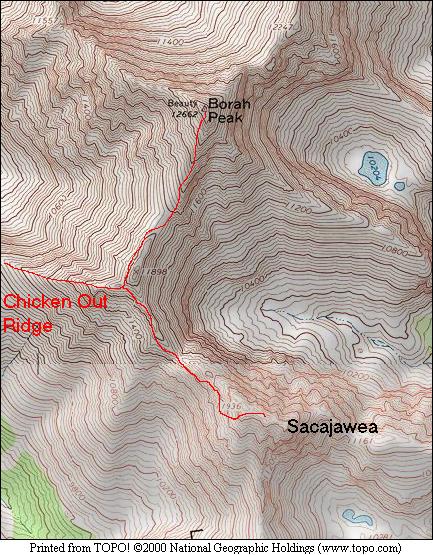

Sacajawea is the 13th-highest peak in Idaho. It sits just south of Mount Borah and can be accessed from the standard route up Mount Borah by leaving that route above Chicken-Out Ridge. This peak is more challenging than Mount Borah’s Standard Route. USGS Elkhorn Creek

I climbed Sacajawea on 10/8/00. Our route generally followed the Northwest Ridge Route. Climbing this peak is a lot more difficult than climbing its bigger neighbor, Mount Borah. Follow the standard route on Borah to the top of Chicken-Out Ridge. Once across the snow bridge, turn right and contour southeast until you can climb to the ridge top which runs toward Sacajawea. The ridge top is studded with rocky fins and is tedious to cross.

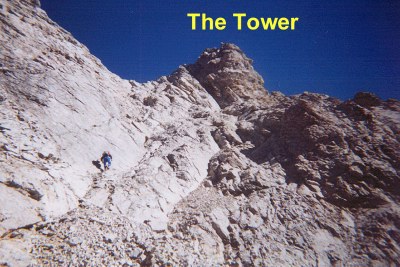

Stay on the ridge crest as much as possible but be prepared to drop off onto the ridge’s South Slopes in places. As you near the lowest point along the ridge (at the base of Sacajawea), the route drops off the ridge by down-climbing a steep ramp. Cross into the col. From this point, the route contours southeast along the South Face of the Northwest Ridge for about 200 yards, crossing three ribs along the way and climbing about 50 feet above the col. After crossing the third rib, a steep ledge and then a gully can be viewed running up steeply to your left around a tower.

Follow this system up and around the tower until reaching the top of a steep rib. From this point, the summit is due east. See photo below.

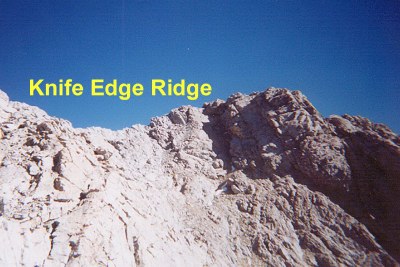

Climb up to your left to reach the ridge crest. Follow the knife-edged ridge to the summit. See photo below.

North Face Direct Route by Wes Collins and Bob Boyles

The North Face Direct Route. Bob Boyles Photo

Overview

Several years ago while sitting in the big snow saddle between Mount Borah’s summit and Chicken-Out Ridge, I first heard and then watched a chair-sized boulder crash down the North Face of Sacajawea. As it gained momentum it made one giant 300-foot bounce and then shattered into a thousand pieces the instant it reconnected with the face. I remember thinking “that place is no-mans land”. For me, Sacajawea sports one of the most impressive North Faces in the Lost River Range. From bottom to top, this 1,600-foot monolith is impossible to miss from the standard route on Mount Borah.

That’s where I first saw it and I’ve been an admirer ever since. In all my hikes up Mount Borah, I can’t think of a trip where I didn’t study the face for potential routes, but self-doubt kept me from any real plan. Then in May 2005, Dean Lords climbed a mixed (WI5) route in a series of steep chimneys on the far right side of the face he named “Broken Wings.” That first ascent made me realize that if the rockfall in a chute is manageable, then a direct route up the face could be had as well. I didn’t forget that exploding boulder, however, so looking for a competent partner was a halfhearted endeavor at best.

In the Fall of 2011, after our ascent of the East Face Direct on Mount Borah, Kevin Hansen and I decided to make a serious try on the North Face of Sacagawea the following Summer. On July 24th, we rendezvoused at the end of the road in the West Fork of the Upper Pahsimeroi with Bob Boyles and Frank Florence. Bob and Frank had their sights set on a new route up the East Face/Northeast Ridge of Mount Borah and wouldn’t be joining us on Sacajawea, but both had made earlier attempts on the North Face of Sacagawea with Curt Olson in the 1970s and 1980s when they and a few other climbers were setting the standard for big alpine climbs in the range.

Bob described a couple of those tries: “Curt had an old, low resolution photo someone had taken that we used as a guide for our proposed route since neither of us had been up in the drainage before for a close look. On this first trip, we packed fairly light and did not bring a lot of technical gear since we figured it wasn’t going to be too difficult, but we were wrong from the start. Our proposed route began with a very steep snow slope and quickly led to technical climbing that would require a lot more gear than we had brought along, so we considered the first trip as promising and planned to come back soon for a full-on assault.

On our second attempt, we came ready for anything, including spending the night on a ledge if necessary. We quickly negotiated the steep snow slope to a small ledge where we packed away our ice axes and racked up our gear for the climbing ahead. Curt took the first lead and I was pleased when the rope kept moving as he progressed up into unknown territory. When Curt got to the end of the rope he set up anchors and soon it was my turn to follow him up the huge face above. The angle was so steep I couldn’t see him above me so we relied on voice commands to know when it was safe to move. I heard Curt from above tell me that he was going to clear a few loose rocks and to be aware.

I tucked in close to edge and waited and all of a sudden dozens of rocks were raining down on me. Just when I thought it was over, I heard a rumble from above and hundreds more rocks started flying down the face. I grabbed a pack, put it over my head and jumped into a fetal position just as the rocks started exploding on the small ledge that was I was standing on. My hands were shaking after the barrage ended and I decided right then and there that I would not get on this route again. But first I had to climb up to Curt’s level to pull his gear in order to get off this mountain. I quickly followed Curt’s path and after a harrowing set of rappels with more rockfall, we safely exited the mountain. He explained that in attempting to clear a few rocks, he dislodged the ‘cornerstone’ rock and the entire gully dumped its contents down on me. I forgave him but decided no route is worth climbing if it means someone is going to get injured or killed in the process.

Curt and I made one more trip to scout out another possible route but our timing was too late and an evening snow storm ended all thoughts of putting up a new route on the North Face of Sacajawea for the season. Curt did talk Frank Florence into one more attempt on our proposed route in 1993 and the two of them made it to our high point where Frank too decided this route wasn’t worth the risk. We did learn a secret from our trips and that is that the North Face is back-cut, or has handholds that are not visible from below.”

Sacajawea (July 25, 2012)

On the morning of July 25th, we all set out a little after 6:00AM. The two mountains share the same ridge, so we hiked together for the first mile and then went our separate ways where the ridge ends in a wide park at 8,900 feet. From our camp to the base of the mountain, Kevin and I dawdled along distracted by the unclimbed buttresses and sub-peaks that circle the basin. It’s hard to tell what the rock will be like until one puts their hands on it, but a good deal of it looked really nice. At about 8:00AM, we reached the base of the climb.

Our line started several meters to the right of Bob, Frank and Curt’s route and would hopefully avoid the chossy terrors of the chimney that they tried. I slipped on a light pair of crampons for the first 80 meters of snow. At camp, we decided to take one set of crampons to save weight. Kevin followed with a belay in his approach shoes and cut a few steps with an ice axe where the snow was too hard to kick. At the randkluft, we chucked the tools back down the slope and I returned for them on the following day.

Kevin got the first rock pitch and we traded leads on superb limestone for the first several pitches. Although gear placements were scarce, the holds were solid and plentiful. Kevin is a master at finding good belays and I felt comfortable every time I was seconding a pitch. My anchors however lack both muscle or imagination and I usually prodded him to place something as soon as he left the belay station. Kevin is also one of those climbers who is absolutely unaffected by heights. He can stand on the edge of the abyss and talk with both hands, seemingly unaware of the void below.

Pitches 4 and 5 cruised up some easy Class 4+ terrain and we climbed several hundred feet in a running belay until I spotted a nice wide ledge off to the left of our trajectory. It was great to finally sit down in a comfortable spot but I had climbed us into a nasty corner where we’d have to descend 50 feet to get back on route or traverse immediately from the ledge under a 40-foot long roof section on much steeper rock. I was glad it was Kevin’s lead and so was he. We only had one real fall on the mountain and it happened shortly after leaving that ledge. Kevin was able to place two nuts and a tiny cam on the way to a short overhanging chimney where he fiddled in another size zero cam and started up.

In the chimney, he had a good undercling on his left hand but when he committed to the move and made a grab at the rock, he could only find a smooth-sloping hold. He somehow stuck the move and reached up with his left hand only to find another sloper. He hung in there for a second or two and then peeled off. As he came down, he reached out and snagged the 2-foot runner hooked to his cam and stopped his own fall before any weight came onto the belay. He down climbed a couple steps and traversed farther out and around the chimney where the roof ended and then continued up.

I was sitting on the ledge at the top of Pitch 9 with my feet dangling over the edge. The clouds continued rolling by and small rocks, knocked down by rope drag, whizzed by out into space. Most of them came by at least 20 feet out from the wall and, after seeing them fly by all day, I’d kind of gotten disconnected to their potential danger, so when I got hit on the forearm by one the size of a softball I was so stunned for a split second, I wasn’t sure what had happened. For a few moments, the pain was blinding and I couldn’t help but squeal like a kid. Kevin heard me from above and instantly figured we were going into rescue mode. I knew I was done leading for the day and although it wasn’t broken, it was completely useless and was the catalyst for several sleepless nights. Worse yet, I couldn’t hold on to a bottle of beer with that hand for nearly two weeks.

We continued gaining elevation on good rock, but the “headwall” above looked like several pitches of steep decomposing mank and by the start of Pitch 10, we confirmed that suspicion. The rock turned from a dark chocolate to a lighter brown color and much of it appeared to barely cling to the wall. To top it off, we saw our first dark cloud roll over the summit and heard a distant peal of thunder.

One of the setbacks to climbing on the Northeast side of the Lost River Range is that you can’t see any weather coming. We’d picked the best day in a 7-day forecast, but Mother Nature had different plans and it looked like we might get rain. Near the top of the pitch, I headed for a large roof section that had a wide crack under its belly, but when I got to it, the crack was too wide for any of our gear. For the anchor, I balanced two nuts into a flaring crack and tossed a sling over a rounded horn. I knew it was all crap and so did Kevin when he got close enough to see. I dismantled it after he put in two slightly better pieces and then did a precarious 60-foot down-climb to his stance on a narrow ledge.

We traded belays and he set out on the “head wall” proper as the first drops of rain started to fall. It wasn’t a hard rain and only lasted about 10 minutes, but it thoroughly soaked everything. While following Pitch 12, it started to rain again and then snow. Needless to say the climbing got pretty slippery and with only one good arm, I was grateful for a snug belay. I cheered up even more when I got to the top of the pitch and found Kevin belaying inside a small bolt hole in the wall. I clipped into another flimsy anchor and Kevin excavated the hole so we could both get out of the slush.

After about 15 minutes, the snow and rain stopped and we could see patches of blue sky overhead. We stayed in the hole waiting for the water to drain off the rock and made guesses on how far we had to go. Kevin led out on Pitch 13. Shortly after he got past the halfway point on the rope, I heard him yell “Off Belay, I’m back in the sun” and I knew he’d made it to the top.

Additional Resources

Regions: EASTERN IDAHO->Lost River Range

Mountain Range: Lost River Range

Year Climbed: 1999

Longitude: -113.77809 Latitude: 44.12269