Article Index

This article was originally published in the January 2022 issue of Idaho Magazine Vol. 21, No 4.

Remote and Idyllic

We never know where life will take us. Often we are bounced around like driftwood in a river by occurrences we could not have foreseen. Fortunately, my unforeseen bounces took me to the remote and idyllic Little Lost River Valley. This is a story that pieces together my observations and explorations with newspaper articles, government reports, and the memories of locals to paint a historical portrait of Dry Creek in the valley.

We never know where life will take us. Often we are bounced around like driftwood in a river by occurrences we could not have foreseen. Fortunately, my unforeseen bounces took me to the remote and idyllic Little Lost River Valley. This is a story that pieces together my observations and explorations with newspaper articles, government reports, and the memories of locals to paint a historical portrait of Dry Creek in the valley.

In October 1978, I moved to Salmon to work for the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), first as a data collector for the Challis Environmental Impact Statement and then as a range technician. When that temporary assignment ended, I secured a job as a crew leader for the BLM’s Young Adult Conservation Corp (YACC). The assignment began in Shoshone. Congress started the YACC in the economically stagnant year of 1977. It was designed to provide young people ages sixteen to twenty-three with one year of conservation-related employment, which theoretically would make them more employable. Like the Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps, which inspired the YACC, the idea was that the country would receive the benefit of conservation–related projects undertaken by the enrollees.

After I had worked six months in Shoshone, the YACC budget was exhausted as a result of mismanagement on the federal level and everyone was laid off until the next fiscal year started on October 1. I picked up a summer job as a backcountry ranger for the Ketchum District of the Sawtooth National Forest. When that job ended and the new fiscal year began, I moved to Idaho Falls as a crew leader for the BLM’s district office.

These twists and turns, which eventually brought me to the Little Lost River Valley, remind me that much history disappears because few write about their experiences. People die and their stories are lost. The artifacts of their lives, like photos and letters sitting in dust-covered boxes, too often pass into oblivion, discarded as useless memories. When my mother was struggling with the cancer that eventually ended her life, I encouraged her to write about her childhood in southern Ohio. She asked, “Who would be interested?” My response was, “I’ve heard all your stories. They’re interesting and important history about the way things were. If you don’t record the history, it will be lost in time. Your grandchildren will never know.” Her handwritten memoir is one of my most prized possessions.

The YACC program lasted for two more years before Congress declined to continue funding the program. It turned out to be the best job I ever had. I ran a ten–person crew for those two years, during which we worked on many different projects but our predominant task was building range fences to delineate cattle–grazing allotments and to protect riparian areas. Most of these fences were constructed in the Little Lost River Valley. I am proud that so many of the crew members I supervised used the job experience they gained to secure good full–time jobs.

Although we worked all over the district, we were stationed in the valley from March to November each year. In a sense, the valley is still a place lost in time. Try searching for the Little Lost River Valley on Google. Other than a short Wikipedia entry describing its physical makeup and a real estate ad or two, your search will be fruitless. Nevertheless, since 1879 homesteaders and their descendants have made a life in the valley, a life for the most part undocumented. The valley is one of those places where the change that happens is almost imperceptible. It is what Idaho was and what I wish it would always be. Its inhabitants are true westerners in every sense of the word.

The Little Lost River runs from north to south through the valley’s arid, high–desert terrain for roughly forty-nine miles. It’s bordered by high, rugged fault–block mountains: the Lost River Range to the west and the Lemhi Range to the east. Thanks to grit, determination, and the harnessing of the perennial streams that flow out of the mountains, hardy people have made a life for themselves here over the years, cultivating the bottomlands and grazing the rangelands.

The river starts in the north at the confluence of Summit Creek and Sawmill Creek. It flows south past long–gone Clyde, where it is joined by Wet Creek and continues south to Howe, bringing water to pastures and fields. The river ends south of Howe, where its remaining water sinks into the lava flows of the Snake River Plain. As it flows south, it is fed by a number of streams, the most important of which are Dry, Wet, Badger, Deer, and Uncle Ike creeks. These streams flow out of the mountains onto massive alluvial fans such as Mulkey Bar, Badger Creek Bar, and Sunny Bar.

Alluvial fans, which are fanned-shaped accumulations of sediments, are characteristic of the Little Lost River Valley and other fault-bounded basins in the mountainous terrain of arid climates. As the mountains on each side are raised and the valley drops because of plate tectonics, the mountains erode and the streams carry the sediments down to the valleys. The fans form where a stream emerges from a confined mountain valley and the water is able to spread out. As it does so, it slows and starts depositing sediment. Over the eons, an alluvial fan can become massive and when it is porous, entire creeks can disappear into it. The earliest settlers harnessed the water from these streams by constructing canals and pipelines, which minimized the amount of water lost to the alluvial fans and evaporation.

Dry Creek is by far the largest of the Little Lost River’s tributaries. Yet its water seldom makes its way directly to the river. This is primarily because since the 1880s, Dry Creek has been diverted and channeled by ranchers to irrigate their land. At the end of the 1880s, enterprising settlers built a canal to divert water out of the main channel in an effort to reduce the water loss through porous alluvial fans. The water was used to irrigate pastures along the valley floor.

The U.S. Geological Survey’s Geographic Names Information System provides no information about why the name Dry Creek was attached to the largest perennial stream that flows out of Idaho’s highest mountain range. It must have been whimsically named by an early settler or maybe by a confused mapmaker. Dry Creek is not only the Little Lost River’s largest tributary, it’s also the Lost River Range’s most scenic drainage. Dry Creek and its tributary, Long Lost Creek, drain a land of lofty, wild mountain peaks that include Mount Breitenbach, Idaho’s fifth–highest summit. The water flows out of the mountains between the Donkey Hills and Taylor Mountain and onto the arid alluvial fan known as Mulkey Bar that forms a broad apron for the Lost River Range.

As the federal government considered ways to stimulate growth in the arid West, a number of schemes were tried. The scheme that directly affected the Little Lost River Valley was the Carey Act, passed by Congress in 1894. It created a framework designed to encourage private companies to develop large irrigation projects. The Act designated the General Land Office (predecessor to the Bureau of Land Management) to identify federal land that was “desert in character” and suitable for reclamation irrigation. The burden was placed on private development companies to choose qualifying land and propose a project to irrigate it. When the project was approved, the company contracted with the government to build the system.

The company then designed and constructed the irrigation infrastructure at its own expense, after which it contracted with settlers to purchase the land and the water supplied by the project, as well as the right to use the irrigation infrastructure. The land purchasers, who paid a minimal entry fee of one dollar plus half the purchase price of the land, were obligated to construct up to a half–mile of ditches from the main canal or lateral ditches to carry water to their land. Landowners had to demonstrate that they owned shares in the project’s water adequate to irrigate their entire property, had constructed a habitable dwelling on their land, had cultivated and reclaimed at least one-eighth of their property, and had paid the second half of the land purchase price. They then were issued a deed to the property. The development company retained liens on the land and water rights until the project was fully paid for and a profit was made, after which it usually bowed out. In most cases, a canal company or irrigation district then would be formed to take over operation and maintenance.

By the 1920s, projects created under the Carey Act transformed Idaho and especially the Snake River Plain. Smaller, lesser–known projects were less successful. One of the least–known and least–successful was the Little Lost River project, undertaken by the Little Lost River Land and Irrigation Company, which was owned or fronted by a man named M.H. Wood. His personal history is now lost in time but his role in promoting the project made him controversial.

The construction of Dry Creek Dam, which was central to this project, began in 1909. Located immediately below the confluence of Long Lost Creek and Dry Creek, the eighty-foot–high backfilled concrete structure was not completed until 1925. The resulting Dry Creek Reservoir covered around one hundred acres and could hold 2,395 acre feet of water at capacity.

When I first visited the dam site with my YACC crew, all that remained of it was a massive ruin composed of unreinforced concrete and gravel rubble—a ghostly monument to the area’s lost history. We looked at it with wonder. Although our curiosity was aroused in those pre-internet days, we were unable to find an explanation for the relic. It took me many years to separate fact from fiction. One BLM employee I asked about the dam incorrectly told me it had failed when it was dynamited in the 1930s. As far back as when I started asking questions fortyyears ago, the dam’s history was already slipping away.

I discovered that when the dam was finished, reservoir water was directed into a wooden pipeline wrapped in wire. The pipeline, constructed much like a wooden barrel, carried Dry Creek water from the reservoir to Corral Creek and then into Wet Creek. But the stored water was intended for use on Carey Act land southeast of Howe and would not benefit existing water–users. This put Wood in conflict with earlier settlers, who had older surface water rights. Disputes over water can turn violent and this one eventually did.

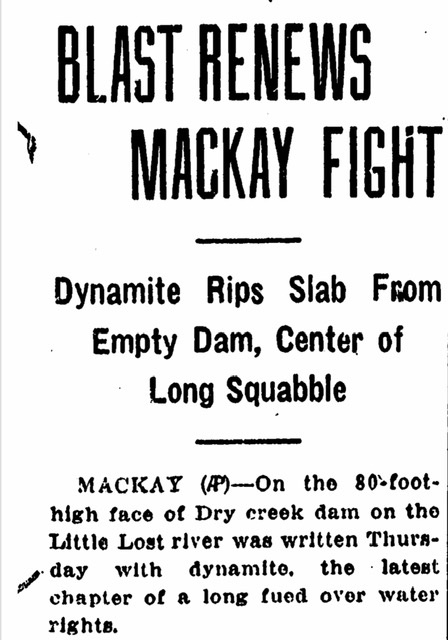

The Idaho Daily Statesman reported in its October 2, 1936 edition, “Merrit Shun, Custer County sheriff, said he is investigating to determine who set off a blast that ripped a twenty-five-foot square slab of concrete from the face of the structure, which forms a reservoir that has been empty for several months.” The article noted, “Decreed [water] right settlers, however, have bitterly resented the fact that this stored water was not available to supplement the scanty natural flow on their own fields and farms. Some years ago, someone shot off a charge of dynamite in [Wood’s] front yard as a warning to him to clear out of the country. Wood refused to be intimidated.”

Nevertheless, at some point after the explosion Wood evidently decided that discretion was the better part of valor. He sold his holdings and left the area for parts unknown.

So the BLM worker I had spoken with was right that eleven years after the dam was completed, in late September 1936, it was dynamited by a person or persons unknown. But he was incorrect about the damage caused by the explosion, which removed a section of concrete yet failed to bring down the dam. Sheriff Shun’s investigation showed that a large amount of dynamite had failed to detonate in one of the dam’s tunnels. I found no evidence that an arrest was ever made.

Evidently, the valley’s project was unsuccessful because too few people purchased the irrigated land, which was what led Wood to take over the land and the water storage rights. After Wood left the area, the Blaine County Canal Company took over the project, according to Jim Andreason, a rancher who operates a ranch near where Dry Creek historically flowed into the Little Lost River. The canal company assumed responsibility for maintaining the dam and the canals. For the next twenty years, the reservoir filled each spring with sufficient water to support a fishery.

According to the few government records I could find, one valley resident named Jesse Strope reported that bull trout, a native species of Dolly Varden trout, were present in the reservoir in the late 1920s. Jesse maintained that she caught only Dolly Varden in the reservoir. Idaho Fish and Game records show the reservoir was stocked with rainbow trout at least as early as 1951. But the reservoir’s fame as a fishing destination came to a sudden end in June 1956, when the dam collapsed. It’s not clear whether lack of maintenance or overflow caused the failure. The water roared down the canyon, ripping out large cottonwood trees and gouging out rock. It ran for miles across the old creek bed until it reached the Little Lost River. The flood caused significant damage to the ranches of the Andreason and Amy families.

Even more tragically, the resulting wall of water killed two youngsters, thirteen-year–old Gerald Whitworth and his twelve-year-old cousin George Dennis Whitworth. Three days after the collapse, the Idaho Sunday Statesman reported the discovery of Gerald’s body under a tangle of downed cottonwoods. The article described the immediate aftermath of the failure: “They were camped near the base of the dam with two adults in a small trailer house. Awakened by the roar of the onrushing water, the men got the boys into a truck, but the water which carried large trees with it knocked the two boys out. Young George was found a few hours later. A Search party of one hundred men have been looking for Gerald ever since.”

The only memorials to the young Whitworth cousins are the gaping hole in the ruins of the dam and dead cottonwood tangles that were washed onto the alluvial fan miles from their original location.

With the dam and the pipeline gone, the water users undertook the task of trying to contain Dry Creek’s water in a usable form. Jim Andreason recalled ranchers “undertaking daily work in the spring with a bulldozer to manage the water.” He said, “Nearly every night, the creek would break out of the channel.” This Sisyphean–like process continued for eight years.

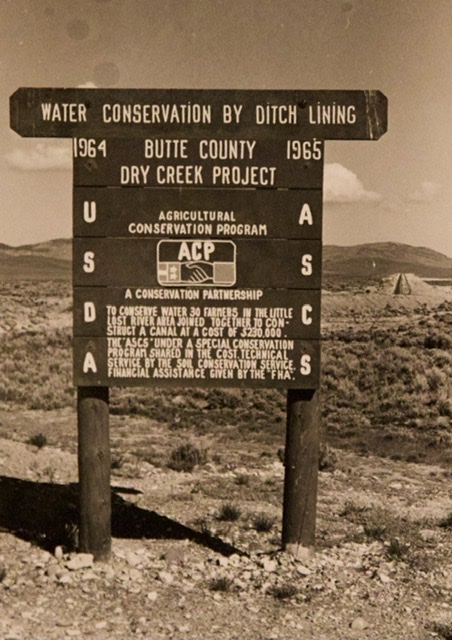

Thanks to Jim and to Jerry Wortley, I learned that eight years after the dam’s demise 30 water users partnered with the Federal Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service (ASCS) to construct a concrete lined canal to once again carry water from Dry Creek to Wet Creek. This project constructed a small check dam downstream from the old dam site. This structure diverted water into a v-shaped concrete canal that carried water from Dry Creek to Wet Creek.

The canal was roughly six feet across at the top with smooth, steep sloping sidewalls. The water flowing through the canal was only a couple of feet deep but it moved quickly. Although the canal was fenced animals, mostly deer and antelope, often fell into the water and could not get out of the smooth, steep-sided structure. There were always dead antelope in the pond at the end of the canal.

Little Lost River water users. Back left – Harry Mays, Bill Butler, Jimmy Andreason, Bill Stauffer, Robert Amy, Emlen Mays, Earl Wortley. Front left – Wayne Bare, Wayne Ishem, Ray Pope, Don Isham, Norman Allen, Arnold Munson. Earl Wortley collection.

One of my last YACC projects in the valley was to mitigate the canal’s danger to wildlife. We built half a dozen wildlife bridges across the canal. This project took us a couple of weeks. When we took breaks, my crew members often dared each other to jump the canal. I would dissuade them by telling them about “the cowboy who fell in.” It turns out that “cowboy” was Cecil Scott, Jim Andreason’s father in law. Jim tells the story “he fell in five miles from the end and rode that canal all the way to the end where he was shot out into the catchment pond. He was in a bad way, having lost lots of skin but he walked all the way back to his pickup.” Jim continued, “Cecil was the only living thing to fall into that canal and survive.”

This canal lasted until the mid-1980’s when it was replaced by an underground pipeline. The pipeline now carries Dry Creek water to a low head power plant near Clyde, Idaho. After turning the turbine the water is discharged into Wet Creek.

After spending 16 months in the valley my crew had built nearly 40 miles of range fence. We experienced the valley in all its rugged glory, from blistering sunshine to frigid cold. Those fences still stand today straight and true. Returning yearly to the Little Lost River valley is for me a sacred pilgrimage. I tip my hat to the ranching families and thank them for their stewardship of this special place.

Next: The Crop Duster Incident