[Editor’s Note: This September 13, 1948 article was referenced on Page 18 of the book in the Mountaineering History Section. The name “Thatuna Hills” appears in the article. This name, which was not adopted by later map makers, refers to a western extension of the Bitterroot Mountains that now is considered the Northern Clearwater Mountains.]

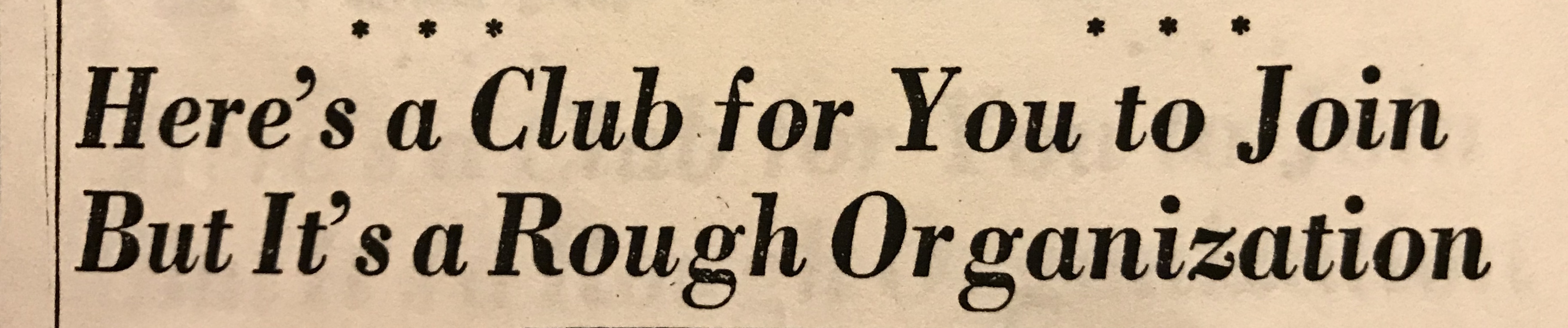

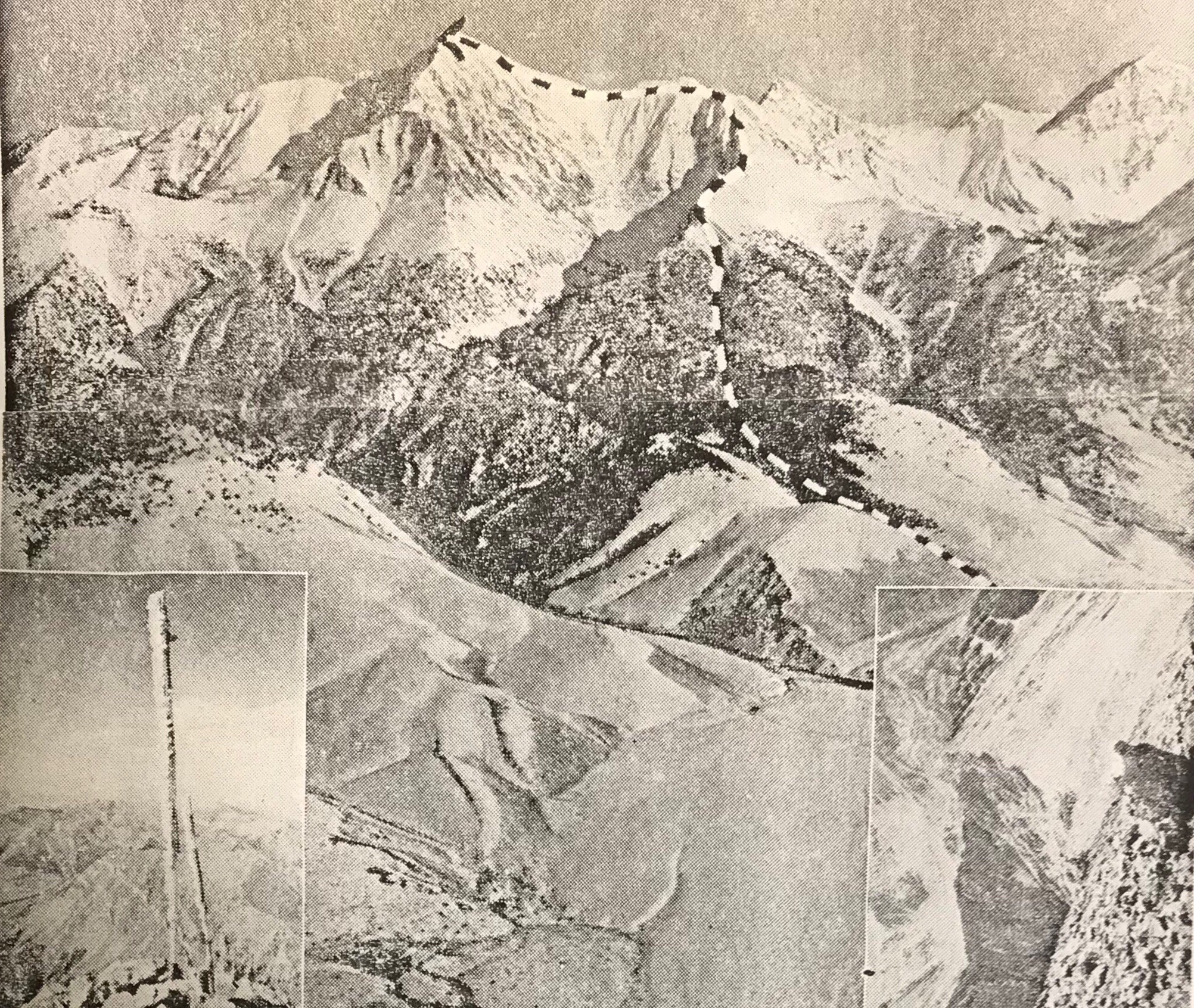

THE LION OF IDAHO, Mount Borah (the highest mountain in the state), is a favorite of Gem state mountain climbers. Rising 12,655 feet, the granite crag is often cloud-draped. Mount Borah is part of the Pahsimeroi Mountains and is in Custer County in the Lemhi National Forest. The photograph was taken from the Statesman’s airplane, Early Bird Number Four. Inset left shows a pole on the summit of Borah on August 18th with a 3-inch layer of rime deposited by cool, moisture-bearing wind. The temperature in mid-Summer rises but little above freezing. Right inset: looking down the other side of Mount Borah discloses a desolate, rugged, rocky and lifeless mass of granite. The dotted arrow shows the route used by several groups of mountain climbers in reaching the summit of Idaho’s highest peak.

By Jack Anderson

Wanna join a club? There’s an exclusive organization which will almost guarantee less than 100 members by 1960. All you have to do to join is climb to the top of a little heap of granite in the middle of Idaho’s rugged area and sign the register atop Castle Peak. There won’t be many names, probably less than 10, on the register. Why climb a mountain? This question is asked to only a handful of Idaho residents, who each Summer go stomping up and down rocky peaks in the Gem state, much to the bewilderment of the majority of inhabitants.

As an old saw goes, “You don’t have to be crazy, but . . .” Mountain climbers can probably advance a multitude of reasons for their breath-taking hobby. Adventure, danger, artistic ideals, exercise, attainment of skill–all could be bona fide reasons for notching one’s way up and down steep rocky hills. In no state of the union does such a minority group have as vast a field to pursue their reckless hobby. Idaho from the play slopes of its Panhandle to the craggy juts of the Southeast is a series of mountain ranges interspersed with valleys and streams.

In the north, the Cabinet Mountains form a purple backdrop for play and fishing on mountain lakes. The Coeur d’Alenes, the Beaverhead Mountains and the Bitterroot Mountains form the eastern boundaries. The Bear River Range, the Blackfoot Range, the Little Lost River Range, the Pahsimeroi Mountains, the Salmon River Range, the Seven Devils, the Thatuna Hills and the Sawtooths round out the mountain fastness.

The Sawtooths are known as the “American Alps” and aside from evoking “oohs” and “ahs” from tourists, provide the mountain climber with considerable territory. Many of the Sawtooths have never seen the shoe of man atop their snow-locked peaks. In the heart of the Sawtooths, the country is upended. From the summit of Mount Hyndman, a portion of weird country known as the “Devil’s Bedstead” may be seen. Jagged quartz obelisks, jumbled, crumbled, interlaced, present a foreboding warning to travelers. It looks as if Nature took the remnants of orderly creation and threw them in a heap.

Who climbs mountains? Many perhaps seriously believe that only escapees from mental institutions would consider climbing to the top of a granite spire and then turning right around and inching back to terra firma level.

Strangely enough, almost anyone can do it and all occupations have contributed to the ranks of intrepid mountain conquerors in Idaho. A well-known priest has climbed some of Idaho’s roughest pinnacles and several bold damsels have journeyed up lesser peaks.

Mountaineering, as seen in the movies, consists of dangling out over space, supported by a thin strand of nylon, vainly swiping at a nearby rock with a pick axe. Actually, much fine climbing can be done with little more than a pair of tennis shoes, stout wind, and a determination to get to the top.

The lion of Idaho, Mount Borah (12,688 feet up to the topmost point), is a stern-looking, starkly impressive crag of grey granite. It rises in insular majesty from the sage-dotted plains of the Little Lost River Valley. Yet it can be climbed in a day with no more equipment than good tennis shoes, warm clothes and a camera for proof. The azure-scraping rocky peak is often cloud-draped and subject to squallish Summer storms and lashing lightning. On a clear day, Borah is a full day’s work but climbable.

In the early days, Mount Hyndman (near Hailey) was considered by settlers to be the highest hill in the state. Recent topographical measurements give Borah the edge by about 150 feet. Hyndman is another boot hill or even a tennis shoe Teton for the average man. However, it is a rough 10-mile walk from car to summit, and vice versa, so most leisurely hill toppers take it as an overnighter. Boulder Mountain, Silver Peak, and Mount McCaleb are all climbs for the amateur with no fancy equipment.

Farther into the canyons (where somber shadows live) rise mountains which have given some of the yodeling Swiss a few bad moments, and caused many to go home empty-sighted of mountain-top views. The Finger of Fate, a needle-like point of non-imposing altitude, baffled a Boston, Massachusetts mountain climbing couple for an entire Summer. They finally gave up and went home to write a book about Idaho mountains. Many of the Alp-type mountains (termed “horn” mountains) have precipitous sides which can be traversed only by “graveling.” Using ropes, spiked shoes and pitons is required on many Idaho mountains.

What’s up there? At the top pf some mountains will be found a pole and a stout iron box. Inside the water-proof container will be a register which the successful sign for posterity and relate the travails of their upward journey. An occasional hawk screams at the violation of his solitude. Trees show the battle with the elements and often have the bark shorn off the windward side from the battering of hailstones and buffeting gales. Lightning scars, snow slides and other examples of nature’s violence in the eons of chipping down the mountains are to be seen.

Caution is the watchword in mountain climbing and the violator seldom gets another chance. An experienced woman climber fell from the cliff-edge of Mount Leatherman nearly 1,000 feet to her death and several other lives have been lost. Although there is no official Idaho mountain climbing club, a group of Oregon mountaineers have formed the Mazamas Club and make mass jaunts up northwest peaks, placing the register boxes for one of the most exclusive clubs in the world.