Robert Fulton was an active Idaho climber in the 1930s. Robert was was fascinated with Mount Borah and wrote several articles chronicling the peak’s early climbing history. His 1935 article in the Idaho Statesman covering his second ascent of the peak (discussed on Page 17 of the book) is set out below.

A TRIP TO THE TOP OF IDAHO

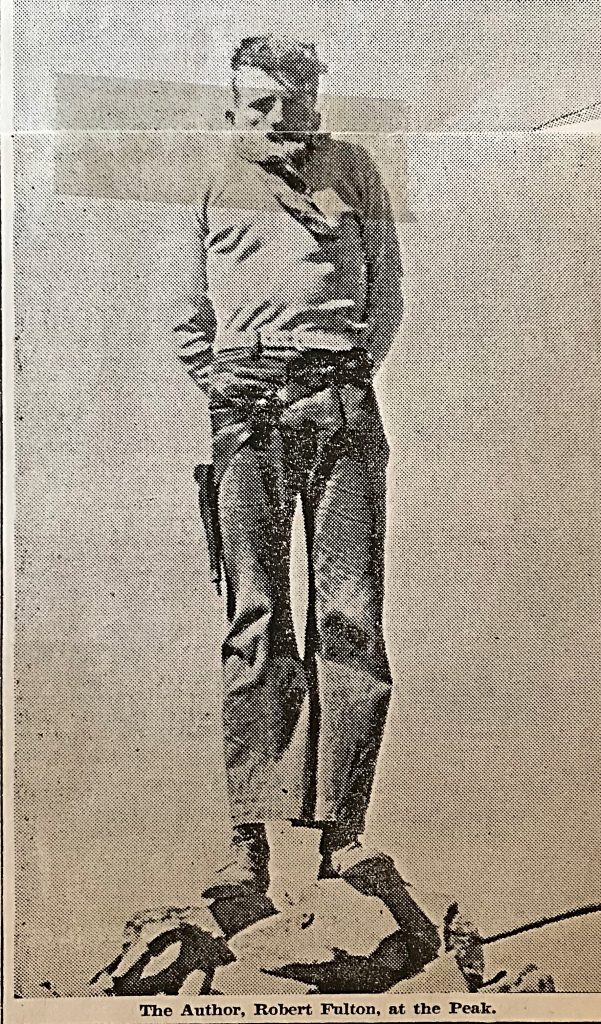

By Robert Fulton

The opening paragraph of a recent biography of a great man or our day states: “During every session of Congress since 1907, a certain magnificent and mysterious man has dominated the Senate chamber even as a certain high, rugged mountain dominates the jagged skyline back home in Idaho.”

The man referred to, of course, is Senator Borah, and the high mountain mentioned is Borah Peak. Today there are being organized “Borah for President” clubs. To complete the author’s metaphor of the first paragraph, I want to tell you of another club: The “Borah Mountain” Club. The membership fee includes $2 or $3 worth of good shoe leather and a generous helping of ambition and energy. This writer claims right of “potential candidate for president” of the Club by virtue of having twice paid the fees mentioned.

In August 1930, Mr. Ray Odle (then of Fort Collins, Colorado) and I deposited the first register in the rock cairn at the summit of Borah Peak. Before 1930, even before recognized as Idaho’s highest, several men had ascended the mountain. Among these are Clyde Jenkins of Twin Falls, Idaho; Norman Wilson from some place in Califonia; and Will Bascom, well-known taxidermist from Mackay, Idaho.

Twenty Climb Peak

Since we established the register in 1930, 20 individuals have accepted the rocky challenge of Borah Peak and have conquered her. During the Summer of 1934, a new government register was placed under the cairn. This was done by the United States Geological Survey group. This last Summer I was working on the German H. Ranch a few miles from Borah Peak. Three of us from the German H. (David Fulton, Fred Strasser of Texas and I) and Francis Smith, representing the Al West Ranch at Dickey, decided to climb the mountain. We selected Sunday, August 25th as the day for the trial.

After an early breakfast at the ranch, we drove to the foothills in an auto. We arrived at timberline soon after 10 o’clock. We found quantities of scattered dead wood just above the timber and, as the Wind was blowing up the mountainside, we decided to build a small signal fire for those at the ranch to see. We rested for several minutes until the fire died before renewing the battle. A few hundred feet above timberline, we reached the top of a long horseshoe-shaped ridge, inclining ever upward and eventually leading to the summit.

Those who have viewed the western face of Borah peak will probably remember this ridge as one of the distinguishing features of the mountain. Many will remember this, as the state highway between Mackay and Challis presents many interesting and inspiring views of this side. This ridge starts far below timberline (heading south) and, after ascending a thousand feet or more above timber, it doubles completely back to the north forming the South Slope of the peak. Within this horseshoe curve is a mighty mountain canyon varying in depth from hundreds of feet on the West Rim to more than 2,000 feet on the east or mountain side of the ridge. This ridge presents a less precipitous trail to follow than if one endeavored to climb directly up the mountain from the North Slope.

Those who have viewed the western face of Borah peak will probably remember this ridge as one of the distinguishing features of the mountain. Many will remember this, as the state highway between Mackay and Challis presents many interesting and inspiring views of this side. This ridge starts far below timberline (heading south) and, after ascending a thousand feet or more above timber, it doubles completely back to the north forming the South Slope of the peak. Within this horseshoe curve is a mighty mountain canyon varying in depth from hundreds of feet on the West Rim to more than 2,000 feet on the east or mountain side of the ridge. This ridge presents a less precipitous trail to follow than if one endeavored to climb directly up the mountain from the North Slope.

We arrived at the top of the ridge rather abruptly and, just as abruptly, the entire bulk of Borah Peak was thrown into bold relief against the morning sky. However, it still seemed far above.

From the top of the ridge, the climbing is often more difficult. There are frequent, almost perpendicular, cliffs to overcome. It is necessary to climb with hands as well as with feet. For this reason, the prospective climber should wear leather gloves.

See Mountain Sheep

Far down the ridge to the right of us, we saw white dots. Mountain sheep? I aimed a revolver high over them and fired. They moved. Convinced that here was real wild game, we planned to get close enough for a shot at them with a camera. We proceeded quietly and soon, when going over the top of a small ridge, we saw (close-up) several head of the same creatures. No, not mountain sheep, just domestic sheep. We figured that they must be lost members of some band and decided to take them home with us on the return.

After more weary minutes that stretched into an hour and then another half, we had rounded the bend of our horseshoe ridge and there opened up (to the right of us) another valley. It was higher, narrower and more mountainous than the one we had left early in the morning. It was dotted here and there with small glacial lakes and high spots of snow. It was the Little Lost River Valley. It is to the east of Borah Peak.

1000 Feet to Go

We had reached the base of the peak itself with only a thousand feet or so of climbing left. Far below us nestled close against the overhanging cliffs was an emerald lake and straight above us towered the elusive summit. We reached the top four hours and 20 minutes after leaving the car. Francis and David were ahead of Fred and me. Fred and I had stopped once too often to rest than had the other two.

It was with a feeling of relief that we saw them contentedly sunning on the windless side of the peak. We joined them in a moment and sprawled immediately to rest. Fred saw a rather large bulky package in David’s hand. “What’s in it?” he asked. “My lunch” said David. “No, I carried yours and mine.” Fred assured him, showing both lunches. Francis glanced at the package and burst into laughter.

Lunch in the Skies

We all questioned him but he could not talk. Instead he tore a hole in the package exhibiting a shirt, a pair of gloves and a pair of socks which he had bought the to the top, not aware of what it contained. We ate lunch on top–2 sandwiches each. As we finished the last crumbs, I believe we must all have been thinking the same thing: “Just wait till supper.”

We read through both registers. The following people have stood on top of Idaho since August 31, 1930:

Roy J. Davis, Pocatello, Idaho. This presents rather an interesting coincidence. I met Davis back in April 1931, at a YMCA gathering at Gooding College. Doctor Davis accompanied the U. of I. southern branch delegation and he was my room guest during that time. Finding his name on top of Borah Peak was the first I had seen it since 1931. R.C. Thoma, C. J. Henecheid, C. V. Hockaday (all of Rupert) were registered, Miriam E. Underhill and Robert M. Underhill of Boston, Massachusetts.

These latter two gentlemen (sic) are famous mountain climbers and they hold the time record for climbing Borah Peak in four hours under adverse conditions. The following men were members of the U. S. Geological Survey party who were engaged in mapping the Borah quadrangle in the Summer of 1934: Lester C. Walker, Twin Falls; Spotty Bruce, Challis; Lyman Marden, Boise; Lee Morrisson, Sacramento; Fred Hayford, Boise; William Eskeldson, Boise; James Wilson, no address given; E. J. Hughes, Portland; and A. H. Marshall, Vancouver, Washington.

“A Stiff Workout”

I talked with these men after they had descended the mountain. They have been to the top of many high mountains in the western states, including our once “highest” Hyndman Peak. They stated that Borah offers a stiffer workout than does the average mountain. Ray Odle (Fort Collins, Colorado) had previously been to the summit of the famous Long’s Peak of his home state. His reaction was that for primitive mountain grandeur, Borah peak outclasses the scenic Colorado attraction.

Two members at least of our party can boast second-best time by having reached the summit in 4 hours and 20 minutes. They are Francis Smith of Darlington and David Fulton of Eden. Fred Strasser of El Paso, Texas and I brought up the rear guard some 15 minutes later. This completes the Borah Mountain Club’s roll call.

Standing on top or the rock cairn, Fred waved his arm over the vast expanse of mountains and valleys and said, “It’s all mine.” We beat him out of most of it, however, before night. It is difficult to say exactly how far one can see from the top. There are two fairly distinct ranges of mountains running north and south far to the east. The second range is the Continental Divide, which marks the boundary of Montana. To the south, the big Blackfoot Butte and the Albion Mountains can easily be distinguished. To the north and west, the Salmon River Mountains and the Sawtooth peaks of Stanley Basin are scattered far below. The scenic grandeur stretching out in every direction cannot be described. It can only be witnessed.

Sheep Left Behind

We left the top after an hour and a half. On the way down, Francis Smith asked us what we intended to do about our sheep. We were all rather tired and did not feel spry enough to chase these woolies down the mountainside, but Fred was the first one to think of a credible way to back out. He stated that he had about decided to leave his until next year when there would be twice as many. This suggestion seemed very reasonable and we all subscribed to it.

We reached the car eight hours and five minutes after leaving and, with razor-sharp appetites, we returned to the ranches. The next day I asked Fred what he thought of Borah Peak. In his easy Texas droll he responded, “Sometime I may even ‘discuss’ climbing it again.” The satisfaction it gives one to conquer this huge pile of granite is worth many times the investment of time and energy required and, whether he ever wishes to return or not, I am sure that no one will regret having once made the climb.

Pingback: Seeing Idaho from Borah Peak by Robert Fulton - IDAHO: A Climbing Guide