[Editor’s Note: Joe Leonard is a man who spent his first 5 years living in the Idaho backcountry in his grandparents’ cabin. From that point, his life just got more interesting each year. He was behind many “first” accomplishments in Idaho, including the first Winter ascent of Mount Regan, the first backcountry skiing guide service in the United States, the first Kayaking School in the country. It is our good fortune that Joe has agreed to share some of his Idaho adventures with us. He is a enthralling writer and you will find the following account of his early Idaho adventures uplifting and rewarding.

This account, including success and failures on Regan and early stories of life in Stanley and Clayton, is a smashing good read which is an excerpt from Joe’s 2016 memoir The Son of the Madam of the Mustang Ranch. Read more about Joe in the Contributors section of this website. Read a newspaper article about the first ascent by clicking on this sentence. Read about the first backcountry skiing guide service by clicking on this sentence.]

LOST AND WANDERING — PART ONE

If the door is open, Angels will enter; if the door is closed, you must listen for the knock.

The lake at the base of Mount Regan, Sawtooth Lake, is a place of many memories and one of the most beautiful places on Earth. I have skied to Sawtooth Lake more than 50 times, the first time in 1966 and the last in 1987–twenty years and each trip etched forever into memory. So many Winter adventures here, so many blue-sky mountain days and so many near-disasters.

Climbing Mount Regan became my life’s passion for 4 Winters: 4 attempts made, 3 attempts failed. It began in 1966 when my climbing partner John Zapp and I set our stars on being the first climbers to make a Winter Ascent of Mount Regan.

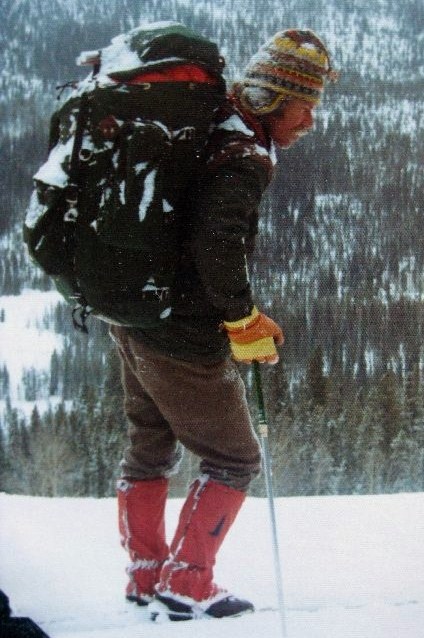

Joe Leonard

Joe’s adventurous climbing partner, John Zapp.

In those days there were only 2 means of transportation available when traveling mountainous terrain during Winter months: snowshoes or alpine skis with seal skins attached by straps. When you were climbing, the hair on the skins would dig into the snow to keep you from sliding backwards and was laid in such a way that it would allow skis to slide forward fairly well. Seal skins were used by the military in WWII and worked quite well for climbing, but they were heavy. The ski boots were heavy and the cable bindings and Marker toe plates were awkward. Skiing uphill was hard going.

In our research, we learned that the Norwegian army used lighter skis with lightweight pin bindings. They had created ski wax that would adhere to the snow when climbing and had no resistance on the downhill run. But their waxes, pin bindings and touring skis were not yet available in the United States. Even REI didn’t have them in their store or catalog. They were common in Europe for skiing in rugged terrain and as we discovered when we later bought ours from Norway in 1970, they made Winter access into the mountains not only more reasonable but traveling on them was efficient and pleasant.

Given our choices at the time, John and I decided that alpine skis and seal skins would be the best alternative for us. Though they would be tedious and slow on the climb into the mountains and more difficult than snowshoes, the trip back out would more than make up the difference, exhilarating and fast in the steep terrain we would encounter. It was Christmas vacation. We had 7 days to get to Stanley, where our journey would begin, ski to the base of the mountain, climb it, ski out and get home in time to return to our jobs by Day 8.

Stanley is a small town in Central Idaho with a population of approximately 50 people in 1966. The setting is beautiful. It is nestled in the Sawtooth Valley at the base of the Sawtooth Mountain Range with the Salmon River meandering through the valley. The first time I saw the Sawtooth Mountains and the little town of Stanley was in 1957. I was 18 years old and will never forget the moment. It was then that I began dreaming of living there one day, a dream that eventually came true.

There was a narrow road following Iron Creek that ran through the treeline at the bottom of the Sawtooths. It was an easy 4-mile ski following Iron Creek Road to its end, where we would begin our ascent to Mount Regan. The distance from the end of Iron Creek Road to the base of the Regan was about 10 miles, a total distance of about 14 miles, with an elevation gain of approximately 3,000 feet.

We packed our gear Thursday evening and left for Stanley after work on Friday, driving through Sun Valley on Highway 93. In those days, it was the only way into the Sawtooth Valley in Winter, a slow winding road that climbed over Galena Summit. At its summit, you could see the entire Sawtooth Mountain Range, a beautiful sight. We took a room that night in the old Sawtooth Hotel, a historical landmark built sometime in the 1800s.

Stanley had a population of around 50 people in the Winter of 1966. Joe Leonard Photo

There were three bars in town: the Rod and Gun Club, the Casino Club, and the Stanley Club. That seemed like a lot of clubs for a population of fifty and we decided there must be some heavy drinkers in town. The Stanley Club had the most cars parked out front and we could hear the roar from the Club a block away. Guessing there just might be some fine local entertainment going on inside, we sauntered down the street and opened the door. Local entertainment there was, happily provided by a couple of Forest Service employees: Tom Kovalicky and Bill James. Tom was the Forest Ranger for the Sawtooth National Forest and Bill worked under him. In the Summer months, they were both smoke jumpers.

When we walked through the front door, Tom and Bill were standing on the bar, three sheets to the wind, teaching their rapt audience the proper way to land after parachuting out of an airplane, explaining that when your feet touched the ground you must immediately do an Alan Roll. “This might be something we need to know just in case we fall off that mountain,” commented John, so we found a place at the bar and became as enthralled with the words of wisdom provided by these two drunken smoke jumpers as were the rest of the listeners.

Totally enraptured with the story they were listening to the onlookers started applauding and chanting, “Demonstration, demonstration!” Tom and Bill started waving their hands and yelling, “Alright! Alright! Clear the floor!” The people sitting in the front row started rearranging the tables and chairs, clearing a space in front of the bar for their lesson. When the space seemed large enough, Tom and Bill yelled “HIYA!” and in unison they dove off the bar, as if they were diving into a swimming pool. It was something to see. Even though they had both consumed their fair share of liquor, they landed on their shoulders, in unison, as smooth as rabbit hair, and rolled to their feet. The crowd cheered and applauded with gusto, John and I right along with them.

They took their bows and turned back to the bar laughing. They bellied up beside us and looked us up and down as if we were some strange beings that had been dropped from the sky, our knickers had drawn them to us like a magnet. “You two are the first strangers we’ve seen in town since I can’t remember when,” said Kovalicky. “Not many people visit Stanley in the Wintertime.”

“What the hell are you doing here?” asked Bill. “We came to climb Mount Regan,” John answered. “Mount Regan?” they both said at once. Kovalicky’s eyes grew to the size of a large snowball. “Hell man, you know no one’s ever climbed that mountain in Winter before? That mountain is in middle of the Sawtooth Range! Do you realize how far that is?” “Yeah, and dangerous. You know there’s a storm coming in?” asked Bill.

“It can’t be much more dangerous then that dive you guys did off the bar. I thought you were both going to break your necks,” I replied. “Just how do you plan to get to that damned mountain?” asked Bill. John answered, “We thought we would ski in.” “Ski in?” said Kovalicky. “Are you guys nuts? It’s almost 15 miles to Sawtooth Lake and you still ain’t there. You still have to cross the lake and Sawtooth Lake ain’t no puddle.”

Bill looked at Kovalicky and said, “Can’t we stop them? There must be something we can do. These guys will get into trouble and guess who will be the ones to have to rescue them.” “Well,” Kovalicky thought a for moment, “I can’t think of anything. After all it’s a free country. I guess it’s alright as long as they know what they’re getting themselves into.” “Do you?” asked Bill, looking back toward us. “I mean, have you done this before?”

John commenced to give them a short resume of his climbing experience. “I climbed and skied in the Alps while I lived there, I’m a ski coach for the College of Idaho, and I have climbed all over the Sawtooths in Summer, including a solo climb of Mount Regan a few years back,” he answered. I saw Kovalicky look at me out of the corner of his eye. “What about you?” he asked.

“I have climbed in Yosemite, the Sierras in the Winter and I climbed Mt. Shasta last January.” I didn’t tell him that I was blown off the mountain. Kovalicky nodded to Bill. They walked a short distance away, just out of earshot, and spoke to each other, arms flailing. When they came back, Kovalicky declared, “We’ve decided to lend a hand. What if we pull you to the end of the Iron Creek Road on our snow machines? That would save you 4 miles of grunt work.”

In those days, I wasn’t as strong as Zapp. The man was an animal. He rode his bicycle over 100 miles a week and, when he wasn’t doing that, he was running the foothills of Boise, regardless of conditions. Nothing would stop him–not mud, nor snow, nor rain.

“Would you do that? That would be fantastic,” I said, trying not to sound too eager. I didn’t want to admit that I was worried more about the trip in than the climb up. “What time tomorrow do you plan on starting out?” Kovalicky asked. “Early,” answered Zapp. We made our arrangements and headed back to the hotel. It was a long, sleepless night.

We met Kovalicky and Bill for breakfast in the Sawtooth Hotel dining room at 7 o’clock sharp the next morning. They had calmed down a bit but were still concerned about the risk they knew we were taking. “So, you’re determined to do this?” asked Kovalicky. “Don’t worry,” Zapp replied, “we’ll be fine. If we see things aren’t going well, we’ll turn back. We’re not insane. Neither of us want to get killed in an avalanche or fall off the mountain.” I nodded in agreement.

We finished a hearty breakfast, knowing it would be the last decent meal we would have for the next 5 or 6 days, and went outside. In the parking lot awaiting us was a truck pulling a trailer with 6 snowmobiles on it. Shortly thereafter, we were joined by several more Forest Service employees who didn’t want to miss out on the fun. There was no question about it–entertainment was in short supply during the Winter in Stanley.

We climbed into the pickup and off we went to Iron Creek Road, where it intersected with Highway 21. We watched as the men unloaded their snowmobiles off the trailer and loaded them up with our cumbersome frame backpacks, heavy with all the gear we were taking: climbing ropes, ice screws, ice axes, pitons, hammers, crampons, sleeping bags, water bottles, climbing boots, collapsible shovels for digging snow caves so we would not have to carry a tent, a Seva stove for cooking and enough freeze-dried food for 6 days.

Kovalicky and Bill had each brought along a rope about 50 feet long. Giving both John and I one end of the rope, they tied the other to their machines and off we went, flying like birds tied to a tether. It was amazing how fast we covered the 4 miles from the highway to the trailhead. We were both quite conscious that the next 10 miles wouldn’t be so easy.

The first attempt begins with a tow from the Forest Service up Iron Creek Road. Joe Leonard Photo

“Tell us when you plan on coming out, perhaps we’ll come back to meet you and give you a ride back to Stanley,” offered Kovalicky.

John said, “That would be great. With the ride you just gave us, we should get to the mountain by dark and, weather permitting, we should be able to climb the mountain in one day. If we can get back down the mountain by dark we could be out the day after tomorrow. If we’re forced to spend the night on the mountain, we won’t be out until Tuesday.”

The calm before the storm. Signing the Iron Creek trailhead register. Soon after, it began to snow.

“That sounds about right if all goes well. If we don’t get to the mountain tonight, add another day to the trip and we won’t be out until Wednesday,” I added. I was already getting apprehensive. A light snow had started falling while John was talking. Kovalicky, Bill and the others wished us good luck and watched as we skied away.

We were making good time. The trail was fairly flat and our skis weren’t sinking too deeply into the snow, but that didn’t last long. Soon it was snowing hard and with each inch of snow that fell, we were using more energy breaking trail. The person who breaks trail always expends more energy than the those behind and we were trading places more often as the snow got deeper.

Before long, we started up a steep ridge and were forced at times to sidestep on steep, narrow areas. By noon, the storm had turned into a blizzard. Snow was falling about an inch an hour and visibility was poor. We had been lured into what seemed to be an easier route, only to find ourselves deep in a canyon too steep to climb out of and we were forced to backtrack. By the time we started up the ridge to Alpine Lake, it was getting late and we were getting tired. Sawtooth Lake was still 2 miles away and 2,000 feet higher. We pressed on but darkness was coming rapidly. Between the blizzard and the twilight, visibility was bad to say the least. We were on a narrow ridge with steep slopes dropping out of sight on both sides. We were traveling blind. The only things visible were large snowflakes falling and swirling around our faces, so thick we could barely see our skis. I knew if we weren’t careful we could easily ski off the edge of the ridge.

We were forced to stop for the night on a flat spot just above Alpine Lake. It was wind-blown and there wasn’t enough snow for a snow cave, but there was enough for a snow trench that would keep us somewhat sheltered from the wind. We starting digging trenches just wide enough for our ground pads and sleeping bags, and hit bedrock only 2 feet down. It was going to be long, long night and I knew we wouldn’t be getting much rest.

After what seemed to be hours, I had finally fallen asleep. I woke abruptly, dreaming that someone was throwing ice cold water in my face. I sat up and looked around but I couldn’t see a thing. The world was black but I could feel freezing water percolating through my down sleeping bag and into my clothes. It took me a few minutes to realize what was happening and was momentarily stunned. It seemed that we were in the middle of a rain storm at 7,000 feet in December. This scenario fell far out of our planning and, worst of all, we hadn’t brought rain gear. My memory flickered on one of the more interesting facts I had read about the Sawtooth Mountains, that they are noted as being one of the coldest places in the Continental United States. Unhappily, I recalled Bill’s words of admonition: “It is dangerous out there.”

“John, John!” I called with a tinge of panic, “It’s raining!” “I know.” he called back. “I thought if it wasn’t bothering you, I must be hallucinating, but I guess not. I think we should pack up and move on. We’d be better off if we were up higher, maybe we can climb above the rain and get back to a nice pleasant blizzard.”

“That’s a good idea.” I replied, “All hell is going to break loose when these steep slopes get saturated.” We could already hear the thunder of avalanches breaking loose all around us. We were safe from avalanches on the ridge, but we were getting soaked and were 15 miles from town. It was a dangerous place to be, much more so than we had anticipated. It was about 9 at night and pitch black when we got our gear gathered up, stuffed in our packs, and got our skis on. Our sleeping bags were too wet to put in the packs so we rolled them up, squeezing the water out of them as best we could, and strapped them on the outside of our packs and started up the mountain.

At the time it seemed the only sensible thing to do. We figured if we got high enough to get out of the rain we could find a suitable place to dig a snow cave, just enough shelter to prevent us from freezing to death. We didn’t get very far. The wet snow on the surface was mixing with the dry cold snow beneath. Our seal skins were icing up layer, upon layer, and building up so fast that we were accumulating stilts of frozen snow on the bottom of our skis. It was impossible to move forward. We had no choice but to remove our seal skins. Without their traction, we were forced to side step as we climbed and there was a lot of climbing ahead, at least 1,000 vertical feet of it.

After struggling for some time against these hopeless conditions, we were finally forced to stop moving up. The situation was grim. We couldn’t just sit and wait for the rain to stop. We had to keep moving lest we freeze to death. Avalanches continued to break loose all around us but avoiding avalanches was only one problem. The more urgent concern was that if we decided to turn back, we could trigger an avalanche and be carried to the bottom of the slope, buried beneath tons of snow. Visibility was non-existent. It would be impossible to determine how steep the slopes were that we would be skiing down. We could easily lose our sense of direction and ski off a ledge or a cliff. Regardless of what we would face if we turned back, there seemed no alternative but to descend. We couldn’t continue on and we couldn’t stop where we were.

We began our descent, listening to the roaring coming from the surrounding mountains as they released their burden of wet snow. The ridge we were on was so steep and narrow that we started carrying our skis, floundering through the snow. It was impossible and, before long, we decided it would be better to ski than to exhaust ourselves post-holing through the deep snow.

As the ridge widened, we were able to traverse the slope on our skis, but were concerned that we might cut an avalanche so we stayed well apart from each other. It was during a traverse that the rain stopped, the sky started clearing and the stars came out, although our initial relief was short-lived. Before long, we became conscious of the extraordinary change in temperature. It was dropping so rapidly that we could feel our fingers start to freeze in our wet gloves. We kept on moving, trying to keep our body heat up. Finally we could see the outline of trees ahead that would lead us to flatter terrain, but the going would not be easy. We came to the first of several deposition areas where the run-off from avalanches above had filled the bottom of the canyon. We had to remove our skis and climb over mounds of ice and broken trees. The snow had set up like concrete. Our clothes had started to freeze, emitting crackling sounds each time we moved.

The snow on the mountain slopes above us was setting up with the cold temperatures so the danger of being hit by an avalanche had decreased, but we had to keep moving. To stop at this point would mean certain death. Each step was brutal. We were breaking through the ice crust that had formed on top of the snow and trail-breaking on the flat proved no easier than on the slopes.

I suggested to John that we discard everything that wasn’t absolutely essential and return later to recover the cache. We dropped our packs and discarded our down sleeping bags, now frozen and hard as steel. I knew my bag was heavy but was shocked to find I had been carrying a 50-pound block of ice. We also discarded our climbing equipment. Having abandoned the better part of our equipment and hoping with the reduced weight for faster travel, we set out again. But still the ice crust wasn’t strong enough to hold our weight. We continued to break through the ice and our skis became all but invisible. It seemed a never ending and constant battle. Our legs were cramping with fatigue and there was a heavy ice crust that was constantly cutting into our ankles. There was no alternative and we pushed on.

At this point, I was feeling not a little despair, although it wasn’t something that I wanted to communicate to John. I was sure that he was probably feeling some despair himself. He stepped to the side of the trail allowing me to take over. Trail-breaking and freezing temperatures were wearing us down and we were both exhausted.

I estimated that we still had 6 or 7 miles to go before we reached the highway and, for the first time, I wondered if we could possibly survive. Even if we reached the highway, we would then have to walk or ski to Stanley, another 5 miles. The temperature continued dropping rapidly and it felt like it was already well below zero. I could feel the hair in my nostrils freeze with every breath I took. Our bodies were expending tremendous amounts of energy just trying to stay warm and our wet frozen clothes were no longer adequate to retain our heat. Our lives were definitely in peril but we continued on, pushing one ski forward and then the other, moving like zombies. We were traveling less than one mile an hour. It would take at least 6 hours to reach the highway.

I tried to focus on anything that would keep me going, to keep me from thinking about how cold and tired I was. So I thought about all the stories I had read and heard about the people who had found themselves in a similar situation, fearing the inevitable but refusing to give up. These adventures and epic struggles that had become part of our collected inheritance. I thought about the people whose story no one had ever heard of–some making it to safety, others who didn’t and were lost both to life and to memory.

My thoughts had given me some small energy and I knew if we were going to be among the survivors we would have to focus and give everything we had to the task at hand–shove one ski at a time forward, transfer weight to the forward ski and pull the trailing ski on, through the thick crust, ignoring it as it rasped against our aching legs, and doing it all over again, one ski at a time, one step at a time. Just keep moving. Sort of a meditation–a meditation on survival.

The repetition went on endlessly, indifferent to the complaints of the mind and body. In this trance-like state, I continued moving forward. Suddenly I was startled out of my reverie. The stillness of the mountains was broken by a voice, not mine and not Johns, but a woman’s voice, clear and inspiring. “He watches over the lost and wandering.” That’s all I heard and, just as suddenly as her voice came, the quiet returned again. It was the most astonishing experience that had ever happened to me.

Some years later I read a book titled “Men Who Have Walked With God.” Many of the men written about had heard a female voice speak to them while on their spiritual journey. Her voice guided them and gave them courage to go on. Her name was Sophia. Perhaps it was her voice I had heard, guiding me on my way, giving me the courage, determination, and strength I needed to continue on.

Throughout history, there have been mountaineers and explorers who have written of similar experiences. Shackleton wrote about “The sense that someone else was present. A presence encouraging me to make strenuous efforts to survive. On expeditions, when I had been at death’s door, I couldn’t identify the stranger, but was aware of a benevolent presence, insisting I shouldn’t give up.”

I have always wondered if those who push themselves to and beyond their limits, understanding the chances they take by so doing, have a spiritual inclination and faith in a higher source. My spirits were instantly lifted, my body not as cold and my skis moved with less effort. The voice had filled me with such energy and joy that I wanted to sing. John must have wondered what had happened to me. I know he could feel my energy but he didn’t comment on it.

It seemed like only a few minutes had passed when we finally reached the trailhead at Iron Creek. It was almost midnight and the sky was crystal clear and filled with stars, giving off enough light that we could see quite well. What I saw under their glow was help for “the lost and wandering.” What John saw were fresh snowmobile tracks.

Tom and Bill had come looking for us and we probably hadn’t missed them by much. We had missed a quick ride out, but at least we wouldn’t have to break trail any longer. When I stepped onto the snowmobile tracks there was yet another miracle. They had come looking for us before the freeze and their snow machines had packed the snow hard as granite while it was still wet. The dropping temperature had given us a two-foot-deep downhill frozen toboggan run, mostly downhill all the way to the highway. All we had to do was stand on our skis, close our eyes, and let the tracks lead us to the highway.

And that was just what we did. We were flying down the road, gliding effortlessly, like we had grown wings as we flew on towards the highway. Fifteen minutes later we were standing in the middle of Highway 21 with only 5 miles to go. We were safe. We would make it. We dropped our packs at the intersection and started skiing down the highway. We had only gone a few feet when we saw headlights in the distance, headed our way from Stanley. Kovalicky and Bill had decided to come back one last time.

Never have I doubted the voice I heard that night. I have called it to mind many times since, when I felt that perhaps I was “lost and wandering.” Always it has remained with me, and many, many times it has spurred me onward. I have often referred back to a passage from Men Who Have Walked with God:

“For mystics, indeed, for all those whose minds are set upon God or Ultimate Spirit as the one goal, it matters not much what is the helping figure the mind fixes upon in route. The way may prove easier because the pilgrim reverently asks for guidance of the Virgin Mary, or of a collective Ancestor, or of Sophia. Wisdom, visualized as a guardian other self.”

THE LOST AND WANDERING – PART TWO

Persistence can be a virtue, or a demon.

After surviving the first attempt at Mount Regan, John and I began planning our next Winter accent of Mount Regan.

While we were skiing out Iron Creek Road, Joe and I started thinking about what we could do differently on our next try at Regan. I didn’t tell him at that moment thinking about another attempt at Regan had been the one thing furthest from my mind at the time. He continued, “Next Fall, say in October, we could take everything we don’t need for the ski-in and cache it near the mountain. When we return in December for the climb, we would be free of the weight and could get to Mount Regan easily in one day. All we would be carrying is our trail food, some tea bags, our Seva Stove, some extra clothes, and this time we will take rain gear. We wouldn’t be carrying more than 20 pounds each. What do you think about that?”

“That sounds good to me.” The prospects of a quick and easy ski-in was enticing. I still thought that the easiest part of the trip was the climb. “Lets do it!”

When October came around, John and I gathered up our climbing gear, everything we thought we might possibly need: ropes, ice ax, pitons, ice screws, hammers, crampons, shovels. This time in the event we would have to sleep on the mountain, we decided to take a tent along with our sleeping bags, freeze-dried food, climbing boots and extra clothes. For the next 2 weeks, we watched the weather closely waiting for perfect weather as we had only one day to hike to the base of the mountain, stash our cache and return home. The weather looked good for the 2nd week in October, so we planned our preliminary expedition for then.

Our day arrived and on Thursday we packed our gear into John’s Volkswagen van and were ready to leave Friday after work. Highway 21 was still open for the Summer season so we didn’t have to drive through Sun Valley and over Galena Summit. We drove up Iron Creek Road, parked the van at the trailhead and pitched our tent in the dark. Winter was already setting in. There was 6-8 inches of snow on the ground.

Next morning, after a quick breakfast of oatmeal and a pot of tea, we headed up the trail as dawn was breaking. We were making good time, carrying about 40 pounds each and the snow wasn’t slowing us down much. It seemed that the trip in December would be a piece of cake. We arrived at Sawtooth Lake in early afternoon and hiked around the East End of the lake looking for the perfect place to cache our gear.

We hadn’t found the perfect spot yet. It had to be easy to find and a place where it wouldn’t be buried under tons of snow. We stopped under a huge old tree for lunch and while I was breaking out the salami, bread and cheese, I noticed Zapp looking hard up the tree. “This is it,” he said after a few minutes of reflection. “We climb as high in this tree as possible and tie our gear to the branches. It’s a no brainer. It will be easy to find the tree. We could even find it in the dark if we had to.” I enthusiastically agreed, and, after lunch, I climbed up the tree 30 or 40 feet and tied the stuff-bags that contained our cache to the tree. The canvas stuff-bags were made of tightly woven oiled canvas and would keep even our down sleeping bags dry. As I climbed back down the tree, I thought when we return in December there will be 10 to 15 feet of snow on the ground and it will be an easier climb.

Secure in the knowledge that our gear was safe, we hiked away. Our trip down the mountain was peaceful and unhurried. The alpine glow on the mountains was beautiful, as if auguring well for our coming Winter expedition. The next 2 months passed quickly. Christmas vacation arrived and it was time to head to the mountains. We were ready, excited and certain that this, our 2nd attempt to climb Mount Regan in Winter would be successful. We called Kovalicky and asked if he was interested in giving us another ride up Iron Creek.

“You guys sure like to suffer,” he laughed. “Pain is the spice of life,” I laughed back. Then came the bad news: he and Bill were off to Montana for the holidays. “Would you like me to find some one else to pull you in?” “That’s all right, we’re traveling light this time.” I explained our cache and told him we should have no trouble. We felt we were already beholden to Tom and Bill and didn’t think it quite right to get the whole town of Stanley involved in our follies.

We arrived in Stanley late Friday and grabbed a room at the now-familiar Sawtooth Hotel. We decided not to go carousing this year and after arranging an early ride to the Iron Creek Road turnoff, we went to bed hoping for a good night’s sleep. The next morning when we sat for breakfast, we were given a note from Kovalicky. “Bill and I snowmobiled up Iron Creek before we left for Montana and packed the snow for you. Good luck up there. It has been a heavy snow year. Don’t get yourselves caught up in an avalanche.” Our ride took us to Iron Creek. We unloaded our gear from the pickup and thanked our driver.

The tracks Tom and Bill left for us were a day or two old but they helped nonetheless. It only took a couple of hours to arrive at the trailhead and it had been a pleasant ski. Once we entered the forest, it became a totally different thing. We were suddenly pushing 12-14 inches of snow ahead of us with every step and the higher we climbed, the deeper it got. With our light packs, it didn’t seem too bad and we congratulated ourselves thinking about our cache waiting for us at the base of Mount Regan. By our calculations we would be at Sawtooth Lake before dark.

There would be plenty of time to collect our gear, pitch our tent, have dinner and get a good night’s sleep. We stopped for lunch on a flat spot below Alpine Lake, right on schedule. Soon after lunch, as we reached the ridge just above the lake, a light snow started falling. The wind came along the ridge with force and we were being pushed around a bit, but with our light loads the going wasn’t bad.

Wordlessly, we skied over our old campsite from the Winter before. It was just getting dark when we topped the ridge to Sawtooth Lake and, in the beauty of the waning light, we removed our seal skins and skied off towards the lake. In short time, we arrived at the lake and started around the East Side to retrieve our gear. Ominously, the landscape was much different now than it was last October. Nothing seemed the same and it seemed there were trees and even some rock cliffs missing. I was disconcerted and felt like we were in a different place altogether. Everything was white, smooth and rounded. Nothing rose out of the snow except Mount Regan. Anxiously, we skied around a ridge expecting to see our tree.

But our tree was gone–it was nowhere to be seen. We looked around us, both of us silently wondering if this was the right place. But all the markers were in place – we recognized our position but our tree was gone. “It’s hard to believe it is buried under 50 feet of snow.” I finally commented “It would be easier to believe it just up and ran away.”

“A tree can hide but it can’t run.” John was trying to make a joke, I didn’t catch the humor. The only other explanation was that it was blown over by the wind. There was no possibility that it had been knocked over by an avalanche. The terrain here wasn’t steep enough. “Well at least we aren’t wet to the bone like last Winter.” John was trying to cheer me up again.

“Yes, and aren’t carrying a 50-pound block of ice on our backs,” I said, trying to join in the humor. “I suggest we have a spot of tea, old chap, before we carve some turns out of here.” Tea was all that we had left and we were both cold, tired, dehydrated and in need of food. We had been anticipating a sort of feast at this point from our stored provisions. I broke out the Seva, primed it, lit the stove, poured the last of our water in our small pot and slowly added snow as the water warmed. I had learned earlier that melting snow to drink or cook with was not as simple as it seemed. It was easy to burn snow if you added to much to a pot and it required patience or else you would be in for a bad cup of tea.

The water was finally getting hot and we brought out our tea bags and cups. When the water started boiling, I reached for the tea pot. I was getting dull witted and clumsy, my gloved fingers weren’t behaving well and I knocked the pot over. For a stunned moment, we both watched as the hot water melted a hole in the snowpack. I gave Zapp a sheepish look: “Sorry about that, shall I try again?”

He didn’t look at me when he said, “I think we better get off the steep part of the mountain before it’s so dark we have to crawl down.” I apologized again and packed up the stove. We strapped our seal skins back on our skis, put our packs on, turned and dishearteningly started out. I felt so guilty about spilling the tea that I went ahead, determined to break trail all the way to the top of the ridge. It was snowing harder and the wind had picked up.

John was close on my heals. “Let’s try Castle Peak next Winter,” he said with little enthusiasm. “OK. It could be that this mountain doesn’t like us. It hasn’t even let us touch it.” I replied, gesturing at the austere mountain face gazing down at us from above. I felt uneasy and wondered if we were in for another epic as the wind and snowfall increased.

By the time we reached the ridge, it had become so dark it was difficult to read the landscape. The wind was howling around us, snow driving into our faces. It was hard to keep our eyes open against the wind and snow, and the steepest part of the descent still lay ahead. “If any avalanche activity is happening, we won’t be able to hear it above this wind,” I shouted to Zapp. “There could be some slab avalanche happening if this wind keeps up,” John yelled back.

That was the last of our conversation on the ridge. We post-holed down. It was too steep and dark to attempt skiing, even without heavy packs. We made it off the ridge in one piece and the wind was less of a problem in the forest below where the trees, swaying above us, absorbed most of its impact. The track we cut on the way up was nowhere to be found so we kept going down, keeping Iron Creek on our right, hoping not to stumble into it. The prospect of repeating our icy descent of the prior year was enough to send chills through our bones.

With our light packs, the trip out was easier than the previous Winter and we weren’t breaking trail through ice-crusted snow. We didn’t feel the panic we had the year before and were still confident that all was well, even though we had been on our skis for over 12 hours with little to eat. We had run out of water and were dehydrated, forced to warm snow in our mouths before swallowing it. Iron Creek was close but it was impossible to get to the water because of the deep snow and lack of visibility.

Fortunately, we found a large dead tree that had fallen across the creek and we knocked enough snow off of it to lay down and reach the water to fill our water bottles. It was just what we needed to give us the energy to make it to the trailhead. We stumbled onto Iron Creek Road around 10:00PM and Highway 21 a little over an hour later. We weren’t so lucky as to get a ride into Stanley this time and had to endure the 5-mile hike through a wind-driven snowstorm. We staggered into town around midnight. The only lights on were at the Rod and Gun Club and they were a welcome sight. We entered the bar covered with snow. There wasn’t a soul in the place. The bartender heard us come in and anticipating a late customer came through the door behind the bar.

“What in the hell happened to you!” he exclaimed. “Dora, Dora, come out here!” While we were waiting for Dora, we started to tell our story. The bartender only had one ear and the missing ear looked as if someone had bitten it off. I thought to myself that the Sawtooth Mountains must be a tough place in more ways than one. Dora came from the back in her night clothes. By that time, the snow we were wearing was melting, creating puddles on the floor. When she saw us she threw her hands up, “Glen!” she cried, “Bring these young fellows into the kitchen so we can thaw them out!”

I could tell by the sound of her voice that she thought Glen was a bit slow figuring out what to do. Dora rushed ahead while we followed Glen into the kitchen. It was located in a room behind the bar and she was already stoking the wood cook stove. “Bring some chairs, Glen,” she demanded. We must have looked as bad as we felt. Dora was obviously concerned and Glen quickly complied as we sat down in front of the already hot stove.

“Coffee will be ready in no time,” she said as she put the pot on the burner over the fire box. “Where did you boys come from?” she questioned. “Were you in a car wreck?” “No, nothing like that, we just skied out of the mountains.” I wondered what she would think of that. “My God,” she exclaimed. “Are you those boys that were here last Winter and nearly froze to death up there?” “I guess that would be us,” sighed Zapp.

“Tom Kovalicky and Bill James have been telling the story of how they saved your lives last Christmas and here you are back again. Are you crazy? What’s wrong with you, are you trying to kill yourselves?” “I am beginning to think that we aren’t too smart,” I replied. “I guess that must be the way of it,” said Glen. While Dora poured our coffee, one-eared Glen left. He soon returned with a bottle of whiskey and poured a generous splash in our cups. “This ought to help thaw you out.” He laughed as he poured some in his cup.

I didn’t know which was thawing me out the fastest, the hot stove or the burning whiskey going down my throat. Dora, left the room, and returned with two heavy wool blankets.“You get out of those wet clothes,” she ordered. She laid the blankets on the kitchen counter and pushed a drying rack closer to the stove. “I’ll be back when you’re decent.” With that she exited the room so we could get undressed. “Glen, tell me when they’re decent,” she called as she closed the door behind her.

We undressed, hung our wet cloths on the rack and pulled the blankets around us. “Glen, are they decent yet?” “It’s all right, Ma. You can come out now,” he called back. Dora came out mumbling about how we should know better than to traipse around in those mountains in the dead of Winter. Glen hadn’t said much for a while. Without asking, he filled our cups with coffee and topped it off with another generous shot of whiskey. I thought maybe Glen wasn’t so slow after all.

“Do you boys know how cold it can get around here in the Winter? He asked. “Why I’ve seen 60 below or better. Stanley is the coldest country this side of the North Pole. You’re damn lucky you’re not stiff as boards. If you froze to death in those mountains, nobody would find you until July and maybe not then, if a bear found you first.” Glen took a drink from his cup. Dora wasn’t finished with us yet. She threw a large frying pan on the stove, filled it with eggs and bacon. “You boys need some food to finish off that chill,” she said.

We hadn’t had food since our salami-and-cheese lunch and were famished. The whiskey was going right straight to our heads. “I hope you’re smart enough to stay out of those mountains from here on out,” she said as she started scrambling the eggs. “You’re already the talk of the town. If you try another stupid stunt like this and freeze to death, I’m going to carve a sign in your memory and it will read: ‘These two fellas came here 3 times; the 3rd time, they stayed forever.”

John and I smiled and contentedly sipped our coffee. As I thought about my trips to Stanley–the breathtaking beauty of the mountains here, the land that felt like God Himself had molded it, the friendliness of the people I had already met. I realized that that was exactly what I had in mind. I wanted to stay here forever: Winter, Fall, Spring and Summer.

John and I returned to retrieve our gear in May and to solve the mystery of our missing tree. We found the top of the tree sticking out of the snow and had to dig fifteen feet down to find our gear. Evidently, we had underestimated the snowfall of the Sawtooth Mountains. Our tree, and our gear with it, had been buried the previous December under at least fifty feet of snow. Between the huge quantities of snow in those mountains and the powerful winds that blow fresh drifts around like sand dunes, our tree (and thus our expedition) never stood a chance.

FAILURE ON CASTLE PEAK

Failure exists only where it is tolerated

It was early in the month of March 1968 and, true to Zapp’s request after our last failure on Regan, we were on our way to climb Castle Peak in the White Cloud Mountains, still seeking the illusive first Winter ascent. Castle Peak is the highest and biggest in the White Cloud Mountain Range of Idaho–a mountain big enough to make its own weather. The start of the attempt began as usual with our trip to Stanley.

We decided to give Mount Regan a pass after our 2 unsuccessful attempts and focused our attention on Castle Peak. Joe Leonard Photo

We arrived in Stanley late in the evening, got our familiar room at the Sawtooth Hotel and went to the Rod and Gun Club to say hello to our old friends Dora and Glenn. “Not again!” Dora exclaimed. “You boys are a caution; I give up.” Glen asked, “Where are you headed this time?” “We thought to attempt a climb of Castle Peak in the White Cloud Mountains this Winter. We decided we would give Mount Regan a rest. She has probably had enough of us for a while,” I answered. There was a man sitting at the bar who couldn’t help but overhear our conversation. He looked at us and asked, “Where are you starting from?”

“The East Fork of the Salmon River. We think that way into the mountain would be the easiest in Winter,” answered John. “How ’bout that, I have a cattle ranch on the East Fork–the name’s Joe Perry.” He stuck out his big callused hand to give us both a shake. “I have been hired by a company who is hoping to mine that area for molybdenum. They have a mining camp at Baker Lake and they hired me to shovel the snow off the buildings they had helicoptered in there. There is no road in that country yet.”

“Are they mining Castle Peak?” I asked. “That seems to be their intention.” John looked at me, “If we are going to climb that mountain we better hurry–it may be gone soon. That would be a shame.” “A sorry event,” I replied. “We may be the first and the last to climb it in the Winter or the Summer.” Mining for molybdenum was devastating. Entire mountains had been erased from the landscape and when a project was completed they looked like it had been bombed with a nuclear weapon.

“That could be true if the dammed conservationists don’t stop them. They have managed to stop the road construction and until the company has a road up there, about all they can accomplish has been done,” explained Perry. “I have an idea that might save you some time and effort and help you to get your mountain climbed.” “What do you have in mind?” I asked. “Well, as I said, they hired me to shovel the snow off the buildings. I tried to get to the camp a month back but the snow was so deep that my horse couldn’t handle it. I was turned around before I was halfway there. There is so much snow up there it is impossible for me to get there on horseback and I don’t know how to ski!” he laughed.

“The camp sits next to Baker Lake at the base of Castle Peak and there will be a lot more snow there. I just don’t see how I am going to get there this Winter and if the snow isn’t shoveled off the buildings, they could collapse.” “That would be a shame. It sure would put a wrench in their plans,” I said but all the while thinking something like that would be a blessing. I was beginning to see where the conversation was leading, but couldn’t figure how it was going to help us climb the mountain.

He continued, “The camp has a generator, a freezer full of meat, a propane cook stove, propane heater and all the fixings and food you would need. You two would have a nice cozy camp. It even has bedding so you won’t have to carry much in. I will give you the key to the place and tell you how to get there if you agree to shovel the roof while you’re there.” “How many miles to the camp”? asked John. “About 12 miles in, but the first 2 or 3 are free of snow so they will go fast.”

Here we go again–the possibility of traveling light and fast. We decided to take advantage of the opportunity again. “We’ll do it. Can you show us on our map how to get there?” John asked. The next morning and well before first light, Dora was kind enough to fix us a big breakfast of bacon, potatoes and eggs. We left Stanley and drove to the trailhead on the East Fork of the Salmon River. Dawn was breaking as we tied our skis across the top of our packs and started walking.

We walked about 2 miles before we encountered enough snow to ski and debated putting our skis on, but the snow had no base. It was granulated and felt like sugar so we continued walking. A mile or so later, we came around a corner and found a freshly-killed deer with mountain lion tracks all around it. We picked up speed and continued on, looking over our shoulders with each step. The snow depth increased rapidly. It was time to break out the skis and skins. We were making good time and reckoned we were almost halfway to the camp. Breaking trail was not bad and I felt certain that we would be at the cabins before dark. We were traveling light again and had only trail snacks and our Seva stove for tea.

I started feeling weak earlier that morning and I wasn’t getting better. Stomach cramps had been troubling me for an hour or so when suddenly I began sweating, became nauseous, and soon after began vomiting violently. Wracked with chills, I was getting weaker by the minute and was beginning to wonder just how sick I might get. John was ahead trail-breaking and I was rapidly falling far behind. When John decided it was my turn to lead he stepped to the side of the trail and, for the first time, realized I had fallen far behind. He skied back to see what was wrong.

“Are you all right?” he asked. “No,” I said, “I don’t feel well at all. I have been vomiting, and have the chills. I’m so weak that I can’t keep up.” “Sounds like food poisoning,” he said looking quite concerned. “You don’t suppose that Dora was trying to teach us a lesson do you?” “How do you feel?” I asked. “Fine,” he replied. “I don’t think Dora would do such a thing,” I said. “If she did, she would have included you in her plan. But that doesn’t preclude the possibility of it just being bad food. The bacon this morning didn’t taste so good. I hope you don’t start feeling bad.”

John gave me a worried look. “Do you think you can go on or should we turn back?” “Lets go on, but only if you are willing to break trail the rest of the way.” “I’m feeling strong. That’s not a problem. Besides, sleeping in a warm cabin tonight would probably help you feel better.” “Go on ahead. I’ll just follow your tracks and catch up later. Keep the cabin warm!” John left and I slowly followed. When it started getting dark, I began to worry. I was weak and tired. I was still vomiting and the chills were getting the best of me.

I realized I was to weak to go on and needed to rest a while so I stopped under a large fir tree and took my pack off. I knew laying in the snow would be a death wish, so I took my pocket knife from my pack and cut as many branches as I could reach off the tree, laying them on the snow for a bed. Perry had told us that there were plenty of blankets in the cabin so, stupidly again, we had left our sleeping bags in the car. All I had was my down parka so I tied the hood tight and laid down on my bed of branches.

An hour later John came back. “How are you feeling?” “The vomiting has slowed down but I am very weak and I still have the chills. How far is it to the cabin?” “I didn’t find it. I gave up when it got to dark to see and decided to come back and check on you.” John gathered up his own bed of branches and then melted some snow for tea. He handed me some gorp and tea, but I just couldn’t keep it down. Realizing we were not making it to the cabins that night, we put our hands in our pockets, got as comfortable as we could on our branch beds, and spent the rest of the night kicking our boots together to keep our feet from freezing. It was one of the longest, sleepless nights I can remember.

At first light John started melting snow into water for tea and for our water bottles. “What do you think?” he asked. “Should we go back or continue on?” “Do you think you can find the cabin?” “I don’t know why not. With light, it shouldn’t be a problem.” “Lets go on then, same as yesterday, but if it starts snowing hard you had better come back for me. It’s doubtful if I will be able to find the cabins without your trail to follow.” I was feeling a little better and the vomiting had stopped, but I was still not able to eat any gorp. I was feeling a little stronger and was no longer chilled.

John’s trail was straight and he followed the trail he had made the day before. Several miles farther, John’s trail began wandering and he had pushed snow over the tracks he made the day before, saving me from the confusion of which one to follow. I followed his tracks to the base of Castle Peak and, at that point, his trail started gaining altitude. I struggled slowly after him until I came to the top of a buttress where, to my joy, I saw the frozen lake. This must be Baker Lake! Daylight was fading as rapidly as my hopes had risen. They fell again just as fast–there was no cabin in sight.

John soon arrived and said, “It’s not here. I skied around the open side of the lake looking for it, making sure it wasn’t hidden lower down over the edge. It just isn’t here.” We pulled our map out again and realized we had climbed to Castle Lake. Baker Lake was lower down and to the north of us, so down we started. All I could handle was skiing long traverses, stopping at the end of a traverse, doing a kick turn to change direction and doing the same again and again. All the time, it was getting darker and darker. When I caught up with John, he had stopped and was packing down the snow with his skis, preparing a bed for another bivouac.

Approaching Castle Lake. Joe Leonard Photo

He explained, “Even if we know the direction to go, it will be impossible to find the cabins in the dark with so much snow. The cabins are probably buried. I think we should spend another night out and search in daylight.” I agreed. I had reached my end and couldn’t go much farther anyway, so we cut more branches for our beds and laid down in our parkas preparing for another sleepless night. Fortunately, it wasn’t snowing. The nights were cold but not desperately so. John started the Seva and shortly we had our tea. It was a difficult night but we managed to stay warm, hands in pockets and slapping our boots together to ward off frostbite in our feet. It seemed forever for dawn to come. When it finally did, we melted more water for tea, ate some gorp and started off, John breaking trail.

“If I don’t find the cabins in the next 2 hours, I think we should start back. That should leave us enough daylight to get to our car.” I agreed and suggested that we should cache our climbing gear again and return later to retrieve it. “Good idea,” he said. And with that, John skied off and I followed. Twenty minutes later, John’s tracks led into a clearing. He had skied straight into a cabin. The snow was as high as the roof and we would have been hard pressed to find it in poor light.

For the next 2 days I laid in bed in that toasty little cabin recuperating. The 1st day, my stomach could only handle honey and tea. But on the 2nd day, I started eating solid food from the cabin’s well-supplied food bin. John fulfilled Perry’s request and had shoveled masses of snow from the cabin roofs. Failed again. There just wasn’t time to climb Castle Peak this trip, so very early on the morning of the 3rd day we ate a hearty breakfast of fried pork chops taken from the freezer and thawed the day before, and left as soon as we could see our ski tracks in the snow.

It hadn’t snowed, so we expected the skiing to be fast on the hard-packed snow and it was. We covered the first 10 miles in less than an hour. The hiking was slower and the deer kill that we found on the trip in was totally gone. The only remaining sign was blood-stained snow and cougar tracks. We reached our car at about 9:00 in the morning and I felt a tinge of disappointment as we drove away. We weren’t having much success with our climbing attempts.

It was still morning when we arrived in Clayton, Idaho, a small silver mining town above the Salmon River. It sits in a canyon so narrow and deep that, in Winter, the sun comes up at about 3:00 in the afternoon and sets at around 3:30. The people who inhabited Clayton in those years were miners who worked underground all day. They probably didn’t notice the lack of sunshine. Clayton consisted of a post office, an old hotel that had seen better days, and a few other buildings that didn’t amount to a hill of beans. Most of the miners lived in houses scattered up a side canyon that got just a touch more sunshine.

The Clayton Post Office was open and we stopped and asked the post mistress where we could get a cup of coffee and something to eat. “Cross the street, go down the stairs,” she said, trying to suppress a smile. We looked and probably smelled pretty bad. We were wearing knickers, our long wool socks were exposed just below the knees, and our hair was longer than normal. We just didn’t look like miners. We probably didn’t look like anything the post mistress had seen before. But I had the feeling she would have enjoyed closing the Post Office and following along as we crossed the street to find our coffee.

We walked across the street and down the stairs, noticing on the way that there were a lot of cars parked on side of the highway–more cars than you would expect in such a small town so early in the morning. We came to the door at the bottom of the stairs, opened it, and were stunned by the volume of noise generated in such a large space. As we stepped inside, we were confronted with at least a hundred people–men and women, but mostly men. They were all rugged miners and their ladies looked like they could handle just about any problem that came along. If you lived in Clayton, Idaho in those days you needed to be strong and, searching the crowd, I could find no exception.

Hesitating, I looked at John and he at me. We had both heard stories of small town Idaho and a close-knit mind set that didn’t tolerate strangers, particularly peculiar-looking ones, but we shrugged at each other and ventured onward. It was early in the morning. What could possibly happen? The hush that fell on the room started one by one as each person turned their head to the door and laid their eyes on us. Several jaws dropped and no one lifted the bottle of beer or the glass they held tightly against their chests. From the moment we opened the door and entered the room the noise diminished until you could hear a mouse wiggle his whiskers.

As the door closed behind us, the crowd started to clear a path. Everybody was stepping back and, in an instant, there was a path cleared all 100 feet to a bar. The lone bartender was looking down the aisle at us. He gazed with such intensity that we had the sensation that we were the only new customers he had seen since the roaring 20s. People sitting at tables stood to get a better look. We started the long march to the bar that lay ahead with all eyes boring down upon us. They were mostly eyes of curiosity. They roamed from our ski boots up the long socks hugged tightly to our legs, and on to the bottom of the wool knickers–short pants that had a leather strap that tightened around the leg below the knee. Above the leather knickers, we looked normal until the eyes arrived at the hair that hung down to our shirt collars.

Their eyes seemed to narrow as the brains behind them searched for a clue as to the nature of these two strange creatures. At one point in the long walk, I felt like we might be long-awaited dignitaries who had finally arrived after much expectation and awaiting. As we moved toward the bar, the miners and their ladies closed in behind us, all moving along as if to join the procession. Nearing our destination, the miners who had been standing at the bar backed away. I guessed they had all grown far-sighted in the dark underground and couldn’t see us if they were too close.

We had come there for breakfast and a cup of coffee, but the closer I got to the bar the more I realized that bacon and eggs were not on the menu and neither John nor I were about to ask to see one. The bartender laid his big calloused hands on the bar like he might bolt over it, and after a short pause in which he boldly stared at us, said “What’ll you have?” Drinking alcohol in those days wasn’t something that either of us did much of, but under the circumstances a big glass of whiskey seemed appropriate. I was not about to ask for a glass of milk.

“A whiskey for me, thanks,” I replied, trying to sound natural. John asked for a Budweiser. The bar didn’t have stools and so we didn’t have to worry about getting too comfortable. In no time, the bartender was back with our drinks and John laid $5.00 on the bar. We both picked up our drinks and turned, trying to smile to the audience who were all on their feet staring at us. They gave us plenty of room. They were standing back about 20 feet and there seemed to be a no-man’s land separating us. The bartender had given us room too. He had moved to the far end of the bar but was also looking our way, his gaze full of suspicion and ill-wishing. Our tentative smiles received no response.

About that time a commotion began off to one side and another aisle began to form. This time it started by a door in the side wall and spread through the crowd. We couldn’t see what was creating the opening in the crowd, but again the crowd filled the opening behind whoever or whatever was coming in. When the separation reached the front row and the last of the miners parted, a man appeared. Not at all of impressive size, only about five-foot six. He looked at us with cold eyes and slowly headed our way. As he came nearer, he swaggered, walking toward us in no hurry whatsoever. My mind struggled to grasp the situation. Who was this man? He couldn’t be the toughest guy around, for there were some monstrous men in the crowd.

Could he be the meanest? He certainly didn’t have to be the bravest. Could this be their leader? He wasn’t moving fast and was taking his time, appraising us as he came on. He was obviously trying to sort out what he was seeing, against all the possibilities of what we might be. I was nearest to him and, as he approached me, his eyes never left mine. His body closed in on me and he stuck his face in mine. I could smell his sour and reeking breath when he said, “What in the hell are you?” He paused as if waiting for an answer. I didn’t have one so he provided some alternatives. “Hippie?… Queer?” He paused again for a moment and with a demanding look and in a low voice, he said, “Or Mountaineer?”

Hippie, queer, or mountaineer, left me no welcome choice. I didn’t know which might be the right answer. In his world, mountaineer could mean a damned environmentalist! I took a step back trying to avoid his bad breath, I lifted my glass and drank the last of the whiskey screwing up my courage and stalling for time. “Mountaineer?” I said in a quiet voice, making my gamble. He turned to the crowd. “It’s all right,” he yelled as he addressed the audience, “they’re Mountaineers!” Everyone seemed to start talking at once and they all moved in closer, asking a million questions.

One asked “What mountain are you climbing?” Another asked, “This time of year? You must be crazy!” A pair of the local women seemed to be casually moving closer. They had twinkling eyes but, under the circumstances, the last thing I needed was a budding romance. And so it continued. One last drink and we said our goodbyes. I couldn’t help winking at the 2 young ladies as I threw back the last of my whiskey. Several of the miners, including the bartender, asked us to come back again–an invitation we accepted warmly but had no intention of following through with. As we left the bar, John and I both wondered aloud what might have happened if my answer had been different. We were glad we didn’t know.

The lesson that I finally learned and vowed never to repeat again was to never enter the wilderness without all the necessary gear that might be called upon for survival in any situation. That lesson would serve me well when I became a mountain guide. John and I finally reached the summit of Castle Peak in May 1969. John moved to New Zealand in 1970. He never did reach the summit of Mount Regan in Winter. I saw him for the last time in 1990; he was on his way to Turkey. I think of him often and hope he has gotten everything out of life that he has wished for. He was an inspiration for me and, without his guidance as my climbing mentor, life would have been much different and considerably poorer. I have no doubt he has found other mountains to climb.

SUCCESS ON MT. REGAN

Emotion is the only difference between success and failure.

The next year I found 2 new climbing partners: Norm Garrison and Kim Johnson. We made an attempt on December 24, 1970 to conquer Mount Regan–my 3rd and, yet another, failed attempt. As before, the trip began well, but night descended too soon and we ran out of light about 100 feet from the summit. We were forced, once more, to descend in the dark.

Approaching the summit on Mount Regan’s long West Ridge. Joe Leonard Photo

Our successful Winter ascent finally occurred on the last day of Winter (1970). My fellow climbers included Norm Garrison, Ron Sargent and Bill Weaver. We arrived at Sawtooth Lake in beautiful weather and spent the first night camped at the base of Mount Regan. We started climbing early the next morning, successfully climbing the East Face of the mountain and were on the summit before noon. We descended the mountain in beautiful weather and skied back to Stanley, all in the same day.

Moving up the ridge on a perfect day. Joe Leonard Photo

It was getting late when we arrived in Stanley, but not too late to stop in the Rod and Gun Club for a quiet celebration. There were 4 locals drinking at the bar, grinning at us as we ordered our beer. We paid for our drinks and settled down at a table to enjoy our accomplishment–the first Winter ascent of Mount Regan. As we were recalling the details of our trip and just starting to relax into our cold bottles of beer, one of the local cowboys backed away from the bar, slowly turned round and sauntered over to our table.

Sargent had a huge red beard that grew out of his face like a broom and the cowboy walked directly towards him. Putting one hand on each side of Sarg’s face, he grabbed his massive beard and lifted him off his chair, turned to his friends and yelled “Hippie!” It made me think that he had been waiting for years and he had finally caught one. Bill Weaver was as fast on his feet as he was on his skis and he calmly told the cowboy that he was mistaken. Ron was no hippie, he was a hippie cowboy. All was hushed for a split second then all at once the cowboys began hooting and laughing.

The big cowboy dropped Sargent back in his chair. I guess hippie cowboys were out of season. The other cowboys sat back on their stools and grabbed for their drinks laughing. I breathed a sigh of relief and realized once again what a different world this was–the people as unique as the mountains they lived in. And I once again decided I really, really liked it.

Success on Mount Regan. The team reaches the summit early in the morning. Joe Leonard Photo

Finally reaching the summit after all the failed attempts was anticlimactic. The speed in which it occurred was because we had finally acquired pin bindings, ski wax and ski boots from Norway. We had cut the edges off wooden alpine skis to decrease weight and attached the pin bindings. The lightweight ski equipment made all the difference. And the beautiful day, full of warm sun, didn’t hinder us in anyway.

Another summit shot. Joe Leonard Photo